Showing posts from category security.

-

The Legacy of Little America: Aid and Reconstruction in Afghanistan

›In 2007, the United States built a $305 million diesel power plant in Afghanistan – the world’s most expensive power plant of its kind. Yet the facility is rarely used, because the impoverished country cannot afford to operate it.

This ill-fated power plant does not represent the only time America has lavished tremendous amounts of money on development projects in Afghanistan that have failed to meet objectives. At a December 7 presentation organized by the Wilson Center’s Asia Program and co-sponsored with the Middle East Program and International Security Studies, Rajiv Chandrasekaran discussed Washington’s expensive attempts to modernize southern Afghanistan’s Helmand River Valley from the 1940s to 1970s – and the troubling implications for U.S. development projects in that country today.

From Morrison Knudsen to USAID

According to Chandrasekaran, a Wilson Center Public Policy Scholar and Washington Post journalist, the story begins after World War II, when Afghanistan’s development-minded king, Zahir Shah, vowed to modernize his country. He hired Morrison Knudsen – an American firm that had built the Hoover Dam and the San Francisco Bay Bridge – to construct irrigation canals and a large dam on the Helmand River. Shah’s view was that by making use of the Hindu Kush’s great waters, prosperity would emerge and turn a dry valley into fertile ground.

Unfortunately, problems arose from the start. The region’s soil was not only shallow, but also situated on a thick layer of subsoil that prevented sufficient drainage. When the soil was irrigated, water pooled at the surface and salt accumulated heavily. Yet despite these challenges, King Shah was determined to continue the massive enterprise. And so, increasingly, was the U.S. government – particularly when Washington began to fear that if it did not support this project, the Soviets would.

In 1949, the United States provided the first installment of what would amount to more than $80 million over a 15-year period. With this aid in hand, Morrison Knudsen not only completed the canals and dam but also constructed a new modern community. Americans called the town Lashkar Gah, but Afghans christened it “Little America.” It boasted a movie theater, a co-ed swimming pool, and a tennis court. Children listened to Elvis Presley records, drank lemonade, and learned English at Afghanistan’s only co-ed school.

However, problems continued to proliferate. Afghans in Lashkar Gah – many of whom had been lured away from their ancestral homelands on the promises of better harvests – did not experience greater farm yields. In the 1960s, the Afghans severed their contract with Morrison Knudsen, and began working directly with U.S. government agencies, including the new U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). The result was some fairly productive farms, but, due in great part to waterlogging and soil salinity, the objective of transforming the region into Afghanistan’s breadbasket was not attained. U.S. funding slowed in the 1970s, and the grand experiment officially ended in 1978, when all Americans pulled out of Lashkar Gah following a coup staged by Afghanistan’s Communist Party.

“We Need To Find a Middle Ground”

What implications does all this have for U.S. reconstruction efforts in Afghanistan today? Chandrasekaran offered several lessons for American policymakers. One is “beware the suit-wearing modern Afghan” who claims to speak for his less-development-inclined countrymen. Another is to be aware that “there is only so much money that the land can absorb.” Finally, it is unrealistic to expect patterns of behavior to change quickly; he noted how Afghans in Lashkar Gah continued to flood their fields even when advised not to do so.

These lessons are not being heeded today, according to Chandrasekaran. He cited a USAID agricultural project, launched in late 2009, that allocated a whopping $300 million to just two provinces annually, with $30 million spent over only a few months. He said that while this effort may have generated some employment, the immense amounts of money at play fueled tensions among Afghans. Furthermore, contended Chandrasekaran, the program “focused too much on instant gratification and not on building an agricultural economy.”

In conclusion, Chandrasekaran insisted that foreign aid is essential in Afghanistan (and at the recently concluded Bonn Conference, Afghan President Hamid Karzai agreed, calling for financial assistance to continue until 2030). He described past aid efforts as either “starving the patient” or “pumping food into him.” We need to find a middle ground, he argued, and said that working on more modest projects with small Afghan nongovernment organizations is one possibility. The problem, he acknowledged, is that Washington is under pressure to spend ample quantities of money, and therefore depends on large implementing partners – no matter the unsatisfactory results.

Michael Kugelman is program associate with the Asia Program at the Wilson Center. -

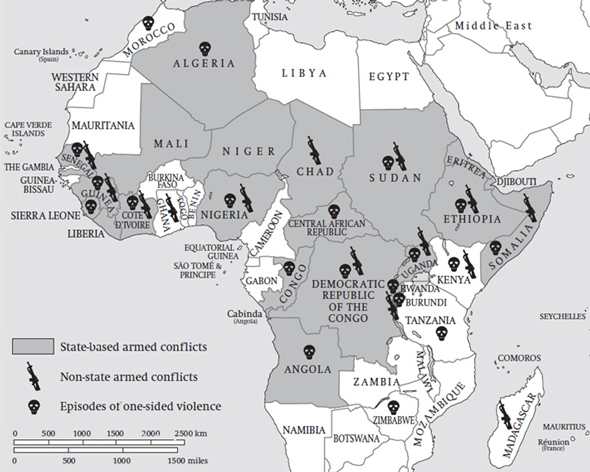

Book Preview: In ‘War and Conflict in Africa’, GWU Scholar Skeptical That Natural Resources Play a Leading Role

›November 30, 2011 // By Elizabeth Leahy MadsenWhile there is widespread agreement that the incidence of conflict in Africa is high, scholars and development agencies alike debate its driving forces and how to move toward solutions. Paul Williams, associate professor in the Elliott School of International Affairs at George Washington University and collaborator with the Wilson Center’s Africa Program, recently published a book that aims to both quantify African conflicts and devise a framework of their causes. In War and Conflict in Africa, Williams evaluates which factors explain the frequency of conflict in Africa during the post-Cold War era and how the international community has tried to build peace and prevent future conflict.

Although there have been promising trends toward establishing peace and democracy in some African countries, the continent still accounts for about one-third of all armed conflicts annually – more than Europe, the Middle East, and the Americas combined. International responses to these events range from focused humanitarian and conflict resolution efforts, to new regional organizations and global strategic and defense partnerships.

Seven of the 16 current UN peacekeeping missions operate in Africa, more than any other continent. The UK government has elected to spend nearly one-third of its development assistance in conflict-affected areas, and more than half of its “focus” countries are in Africa. In 2008, the Department of Defense created the U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM), whose commander, General Carter Ham, in a speech to Congress earlier this year, described “an insidious cycle of instability, conflict, environmental degradation, and disease that erodes confidence in national institutions and governing capacity,” as motivation for American military attention. “This in turn often creates the conditions for the emergence of a wide range of transnational security threats,” he said.

Evaluating the Ingredients of Conflict

Williams rejects earlier theses that attribute conflict across the continent to a single factor, such as the boundary legacies of colonialism, greed, or ethnicity. Instead, he characterizes African conflicts as “recipes” composed of case-specific mixes of factors, many of which are underlying and only some of which are sufficient triggers for conflict. “Collier is wrong,” Williams explained in an email interview. “Governance structures are always an important part of the buildup to war.”

Five “ingredients” of conflict are examined in-depth: neo-patrimonial governance structures; natural and human resources; sovereignty and self-determination; ethnicity; and religion. Among these, the book presents a fairly skeptical view of resources, ethnicity, and religion as immediate drivers of conflict. This assessment that environmental and identity issues are not sufficient to generate conflict on their own aligns with the book’s overarching argument: The decisions of political actors can instigate conflict or motivate peace from virtually any context, manipulating factors such as ethnicity and religion for their own advantage.

Effects of Natural Resources Are “Open-Ended”

A widely publicized thread of peace and conflict studies posits that resources, either when scarce or abundant, have an important role in triggering wars. A 2009 UN Environment Programme report found that 40 percent of all internal conflicts since 1950 “have a link to natural resources.” Recent peer-reviewed research has suggested that certain environmental changes increase the likelihood of civil conflicts or are directly responsible for it. Yet the question remains a source of much debate. For his part, Williams asserts that natural resources alone are insufficient to cause conflict.

War and Conflict in Africa presents several reasons that researchers and policymakers should avoid linking resources directly to conflict without considering the influence of intervening factors. Chief among them is that the value of any resource is socially constructed – no stone or river carries worth until humans decide so. Therefore, Williams argues that “it is political systems, not resources per se, that are the crucial factor in elevating the risk of armed conflict.”

The book suggests that two extant theories successfully demonstrate the connection between resources and conflict. The first body of research finds that conflict is more likely in regions that face a combination of resource abundance and a high degree of social deprivation. The second theory suggests that the link between resources and conflict lies in bad governance, whether exploitative or unstable. Both theories have explanatory power for Williams’s central line of thinking: Resources can be either a blessing or a curse, depending on leadership.

“Inserted into a context where corrupt autocrats have the advantage, resources will strengthen their hand and generate grievances,” he writes (p. 93). “Inserted into a stable democratic system, they will enhance the opportunities for leaders to promote national prosperity.”

Population and the Environment

Williams does accede that particular resource factors – land and demography, for example – may play a more significant role than others in conflict, but calls for more research. In a brief discussion of population age structure, the book suggests that there is no single relationship between demography and conflict but multiple ways that the two can relate. Williams mentions the theory that “large pools of disaffected youth” with few opportunities can raise the risk of volatility. However, he then notes other research showing that the most marginalized members of certain African societies are less likely to participate in political protests and more likely to tolerate authoritarian rule than those who are better off.

“The most marginalized from society are the truly destitute without patrons and suffering from severe poverty. They may well be inclined to join an insurgency movement once it begins to snowball but they will not usually play a key role in establishing the rebel group in the first place,” Williams said. However, “any time there are large pools of poor and unemployed youth there is the potential for leaders to manipulate them.”

On environmental resources, the book argues that land should be a central feature of quantitative research on the relationship between resources and conflict. Most African economies continue to rely on agriculture, and Williams observes that land has been “at the heart” of many conflicts in the region through a variety of governance-related mechanisms relating to its management and control. He places less emphasis on water scarcity as a potential factor in conflict, noting that the 145 water-related treaties signed around the world in the past decade auger well for cooperation rather than competition.

Williams is also dubious of emerging arguments that climate change could directly increase the incidence of conflict, either through changing weather patterns or climate-induced migration.

“Because armed conflicts are, by definition, the result of groups choosing to fight one another, any process, including climate change, can never be a sufficient condition for armed conflict to occur,” he argued. “Armed conflicts result from the conscious decisions of actors which might be informed by the weather but are never simply caused by it.”

No Simple Formula

Williams is not the only observer to find the narrative that resource shortage (or abundance) precipitates conflict too simplistic. His message to policymakers is a common refrain from academics and analysts seeking to counteract policymakers’ quest for simple formulas: We need more data.

“When deciding how to spend our money, we need to spend more of it on developing systems which deliver accurate knowledge about what is happening on the ground, often in very localized settings,” Williams said. War and Conflict in Africa contributes to a more complex understanding of the political actors and systems that catalyze or prevent conflict and offers a cautionary tale to those who seek only proven, easy predictions.

Elizabeth Leahy Madsen is a consultant on political demography for the Wilson Center’s Environmental Change and Security Program and senior technical advisor at Futures Group. She was previously a senior research associate at Population Action International. Full disclosure: She was a graduate student of Paul Williams’ in 2007.

Sources: DFID, Englebert and Ron (2004), Ham (2011), Hsiang et al (2011), Kahl (1998), Leysens (2006),Østby et al (2009), Radelet (2010), Themnér and Wallensteen (2011), UNEP (2009), UN Peacekeeping, Williams (2011)

Image Credit: Conflicts in Africa 2000-09, reprinted with permission courtesy of P.D. Williams, War and Conflict in Africa (Williams, 2011), p.3. -

UNiTE To End Violence Against Women

›November 25, 2011 // By Schuyler NullToday is the International Day to End Violence Against Women, an awareness and advocacy campaign organized by a host of UN agencies and offices “to galvanize action across the UN system to prevent and punish violence against women.”

Gender equity and inequity play a role in a myriad of international development, health, security, and even environmental issues, from rape as a weapon of war; demography’s effects on political stability; maternal health and its impact on child development; women’s rights as a social stability issue; and the disproportionate effect of climate change on rural women.

The numbers around gender-based violence are staggering. According to the UN:

Here are some of New Security Beat’s posts on gender-based violence and inequity and their intersection with development, the environment, and security:- 70 percent of women experience physical or sexual violence from men in their lifetime.

- Approximately 250,000 to 500,000 women and girls were raped in the 1994 Rwandan genocide, and in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), at least 200,000 cases of sexual violence, mostly involving women and girls, have been documented since 1996, though the actual numbers are considered to be much higher.

- In the United States, one-third of women murdered each year are killed by intimate partners; in South Africa, a woman is killed every six hours by an intimate partner; in India, 22 women were killed each day in dowry-related murders in 2007; and in Guatemala, two women are murdered, on average, each day.

- Over 60 million girls worldwide are child brides, married before the age of 18, primarily in South Asia (31.1 million) and sub-Saharan Africa (14.1 million).

Gender-Based Violence in the DRC: Research Findings and Programmatic Implications:

Dr. Lynn Lawry, senior health stability and humanitarian assistance specialist at the U.S. Department of Defense, presented findings from the first cross-sectional, randomized cluster study on gender-based violence in the DRC at the Wilson Center this year. The first of its kind in the region, the population-based, quantitative study covered three districts in the DRC and a total of 5.2 million adults, comprehensively assessing gender-based violence, including its prevalence, circumstances, perpetrators, and physical and mental health impacts.

Pop Audio: Judith Bruce on Empowering Adolescent Girls in Post-Earthquake Haiti: “The most striking thing about post-conflict and post-disaster environments is that what lurks there is also this extraordinary opportunity,” said Judith Bruce, a senior associate and policy analyst with the Population Council. Bruce spent time last year working with the Haiti Adolescent Girls Network, a coalition of humanitarian groups conducting workshops focused on the educational, health, and security needs of the country’s vulnerable female youth population.

The Walk to Water in Conflict-Affected Areas: Constituting a majority of the world’s poor and at the same time bearing responsibility for half the world’s food production and most family health and nutrition needs, women and girls regularly bear the burden of procuring water for multiple household and agricultural uses. When water is not readily accessible, they become a highly vulnerable group. Where access to water is limited, the walk to water is too often accompanied by the threat of attack and violence.

Weathering Change: New Film Links Climate Adaptation and Family Planning: “Our planet is changing. Our population is growing. Each one of us is impacting the environment…but not equally. Each one of us will be affected…but not equally,” asserts the new documentary, Weathering Change, launched at the Wilson Center in September. The film, produced by Population Action International, explores the devastating impacts of climate change on the lives of women in developing countries through personal stories from Ethiopia, Nepal, and Peru.

Sajeda Amin on Population Growth, Urbanization, and Gender Rights in Bangladesh:

The Population Council’s Sajeda Amin describes the Growing Up Safe and Healthy (SAFE) project, launched in Dhaka and other Bangladeshi cities last. The initiative aims, to increase access to reproductive healthcare services for adolescent girls and young women, bolstering social services to protect those populations from (and offer treatment for) gender-based violence, and strengthen laws designed to reduce the prevalence of child marriage – a long-standing Bangladeshi institution that keeps population growth rates high while denying many young women the opportunity to pursue economic and educational advancement.

No Peace Without Women: On October 31, 2000, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 1325, which called for women’s equal participation in all efforts to maintain and promote peace and security; however, little progress has been made over these last 10 years and women remain on the periphery when it comes to post-conflict reconstruction and development. A report from the humanitarian organization CARE concedes that “much of the action remains declarative rather than operational.”

Addressing Gender-Based Violence to Curb HIV: At last year’s International AIDS Conference in Vienna an astonishing development in the campaign to stem the spread of HIV/AIDS was unveiled – a microbicide with the ability to reduce the risk of transmission of HIV. This welcome development coincides with an intensified focus on women’s health and security needs among donors, especially the United States.

The Future of Women in the MENA Region: A Tunisian and Egyptian Perspective: Lilia Labidi, minister of women’s affairs for the Republic of Tunisia and former Wilson Center fellow, joined Moushira Khattab, former minister of family and population for Egypt, this summer at the Wilson Center to discuss the role and expectations of women in the Egyptian and Tunisian revolutions, as well as issues to consider as these two countries move forward.

Sources: UN Secretary-General’s Office. -

Jill Shankleman for the U.S. Institute of Peace

Lifting the Veil: What Can We Learn From EITI Reports?

›November 22, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Jill Shankleman, appeared on the United States Institute of Peace’s International Network for Economics and Conflict blog.

The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), launched in 2002, now has 35 participating countries that have committed to publish annual, independently verified reports on all mining, oil, and gas payments made by companies to governments and all revenues received by governments from these extractive industry companies. The EITI is based on the premise that making public reliable information about extractive industry payments will make corruption and theft of “resource rents” more difficult and will enable informed debate amongst citizens and politicians about how to use resource wealth. While initially some governments could object to joining on the grounds that EITI was “a bad boys’ club,” Norway is now a fully engaged member; the United States has just announced that it will participate; and Australia stated it will pilot-test the system.

The participants in EITI also include Liberia, East Timor, Sierra Leone, and Côte d’Ivoire, which, as post-conflict states, depend more than most on effective management of their resource wealth to establish the foundations for sustained economic growth. Citizens, journalists, and government officials in all the EITI countries now have access to some information on what extractive industry companies are paying to the government and what the government is receiving.

However, examination of country EITI reports reveals several shortcomings in reporting. What do the reports tell us beyond the headline numbers (i.e., total revenues and the size of any discrepancy between what companies report paying and what governments report receiving)? What do they tell us about revenue trends or about the significance of these revenues in total government receipts? How many countries have a pattern similar to Tanzania whereby the largest contribution documented in their first report was through companies collecting payroll taxes on behalf of the government? What is the value of “social investments,” training levies, or research and development contributions made by extractive industry companies? Where, and to what extent, do oil, gas and mining companies make payments to local governments?

Continue reading on the International Network for Economics and Conflict blog.

Jill Shankleman is a senior scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center and former senior social and environmental specialist at the World Bank.

Video Credit: “Transparency Counts,” courtesy of vimeo user EITI International. -

Lessons From Peru to Nepal

Glacial Lake Outburst Floods: “The Threat From Above”

›

“We have never experienced so many potentially dangerous lakes in such a short period of time,” said Alton Byers of The Mountain Institute (TMI) during a roundtable discussion on glacial melt, glacial lakes, and downstream consequences at the Wilson Center on October 26. “There have always been glacial lake outburst floods,” said Byers. What has changed is how quickly these lakes now grow. “Suddenly, you wake up in the morning, and now there are hundreds and hundreds of these lakes above you – the threat from above,” he said.

-

In Colombia, Rural Communities Face Uphill Battle for Land Rights

›November 14, 2011 // By Kayly Ober“The only risk is wanting to stay,” beams a Colombian tourism ad, eager to forget decades of brutal internal conflict; however, the risk of violence remains for many rural communities, particularly as the traditional fight over drugs turns to other high-value goods: natural resource rights.

La Toma: Small Town, Big Threats

In the vacuum left by Colombia’s war on drugs, re-armed paramilitary groups remain a threat to many rural civilians. Organized groups hold footholds, particularly in the northeast and west, where they’ve traditionally hidden and exploited weak governance. Over the past five years, their presence has increased while their aims have changed.

A recent PBS documentary, The War We Are Living (watch below), profiles the struggles of two Afro-Colombian women, Francia Marquez and Clemencia Carabali, in the tiny town of La Toma confronting the paramilitary group Las Aguilas Negras, La Nueva Generacion. The Afro-Colombian communities the women represent – long persecuted for their mixed heritage – are traditional artisanal miners, but the Aguilas Negras claim that these communities impede economic growth by refusing to deal with multinationals interested in mining gold on a more industrial scale in their town.

For over seven years, the Aguilas Negras have sent frequent death threats and have indiscriminately killed residents, throwing their bodies over the main bridge in town. At the height of tensions in 2010, they murdered eight gold miners to incite fear. Community leaders know that violence and intimidation by the paramilitary group is part of their plan to scare and displace residents, but they refuse to give in: “The community of La Toma will have to be dragged out dead. Otherwise we’re not going to leave,” admits community leader Francia Marquez to PBS.

La Toma’s predicament is further complicated by corruption and general disinterest from Bogota. Laws that explicitly require the consent of Afro-Colombian communities to mine their land have not always been followed. In 2010, the Department of the Interior and the Institute of Geology and Minerals awarded a contract, without consultation, to Hector Sarria to extract gold around La Toma and ordered 1,300 families to leave their ancestral lands. Tension exploded between the local government and residents.

The community – spurred in part by Marquez and Carabali – geared into action; residents called community meetings, marched on the town, and set up road blocks. As a result, the eviction order was suspended multiple times, and in December 2010, La Toma officially won their case with Colombia’s Constitutional Court. Hector Sarria’s mining license as well as up to 30 other illegal mining permits were suspended permanently. But, as disillusioned residents are quick to point out, the decision could change at any time.

“Wayuu Gold”

Much like the people of La Toma, the indigenous Wayuu people who make their home in northeast Colombia have also found themselves the target of paramilitary wrath. Wayuu ancestral land is rich in coal and salt, and their main port, Bahia Portete, is ideally situated for drug trafficking, making them an enticing target. In 2004, armed men ravaged the village for nearly 12 hours, killing 12, accounting for 30 disappearances, and displacing thousands. Even now, seven years later, those brave enough to lobby for peace face threats.

Now, other natural resource pressures have emerged. In 2011, growing towns nearby started siphoning water from Wayuu lands, and climate change is expected to exacerbate the situation. A 2007 IPCC report wrote that “under severe dry conditions, inappropriate agricultural practices (deforestation, soil erosion, and excessive use of agrochemicals) will deteriorate surface and groundwater quantity and quality,” particularly in the Magdalena river basin where the Wayuu live. Glacial melt will also stress water supplies in other parts of Colombia. The threat is very real for indigenous peoples like the Wayuu, who call water “Wayuu gold.”

“Without water, we have no future,” says Griselda Polanco, a Wayuu woman, in a video produced by UN Women.

The basic right to water has always been a contentious issue for indigenous peoples in Latin America – perhaps most famously in Cochabomba, Bolivia – and Colombia is no different: most recently 10,000 protestors took to the streets in Bogota to lobby for the right to water.

Post-Conflict Land Tenure Tensions

Perhaps the Wayuu and people of La Toma’s best hope is in a new Victims’ Law, ratified in June 2011, but in the short term, tensions look set to increase as Colombia works to implement it. The law will offer financial compensation to victims or surviving close relatives. It also aims to restore the rights of millions of people forced off their land, including many Afro-Colombian and indigenous peoples.

But “some armed groups – which still occupy much of the stolen land – have already tried to undermine the process,” reports the BBC. “There are fears that they will respond violently to attempts by the rightful owners or the state to repossess the land.”

Rhodri Williams of TerraNullius, a blog that focuses on housing, land, and property rights in conflict, disaster, and displacement contexts, wrote in an email to New Security Beat that there are many hurdles in the way of the law being successful, including ecological changes that have already occurred:Perhaps the biggest obstacle is the fact that many usurped indigenous and Afro-Colombian territories have been fundamentally transformed through mono-culture cultivation. Previously mixed ecosystems are now palm oil deserts and no one seems to have a sense of how restitution could meaningfully proceed under these circumstances. Compensation or alternative land are the most readily feasible options, but this flies in the face of the particular bond that indigenous peoples typically have with their own homeland. Such bonds are not only economic, in the sense that indigenous livelihoods may be adapted to the particular ecosystem they inhabit, but also spiritual, with land forming a significant element of collective identity. Colombia has recognized these links in their constitution, which sets out special protections for indigenous and Afro-Colombian groups, but has failed to apply these rules in practice. For many groups, it may now be too late.

As National Geographic explorer Wade Davis said at the Wilson Center in April, climate change can represent as much a psychological and spiritual problem for indigenous people as a technical problem. Unfortunately, as land-use issues such as those faced by Afro-Columbian communities, the Wayuu, and many other indigenous groups around the world demonstrate, there is a legal dimension to be overcome as well.

Sources: BBC News, Colombia Reports, International Displacement Monitoring Centre, PBS, Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, UN Women. The War We Are Living, part of the PBS series Women, War, and Peace, was instrumental to the framing of this piece.

Image and Video Credit: “Countryside Near Manizales, Colombia,” courtesy of flickr user philipbouchard; The War We Are Living video, courtesy of PBS. -

Food Security, the Climate-Security Link, and Community-Based Adaptation

›In “The Causality Analysis of Climate Change and Large-Scale Human Crisis,” published in last month’s Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, authors David Zhang et al. write that changes in food supply are key indicators for the likelihood of climate change-induced conflict. Adding to the debate on the links between climate and conflict, the authors write that their purpose was to discover the specific causal mechanisms behind the relationship by analyzing various climate- and crisis-related variables across several periods of peace and conflict in pre-industrial Europe. They found that “climate-induced agricultural decline,” as opposed to resource scarcity caused by rapid population growth, was the clearest indicator of impending crises. “Malthusian theory emphasizes increasing demand for food as the cause,” write the authors, “whereas we found the cause to be shrinking food supply” – a distinction with “important implications for industrial and postindustrial societies.”

In “Using Small-Scale Adaptation Actions to Address the Food Crisis in the Horn of Africa: Going beyond Food Aid and Cash Transfers,” published in Sustainability, authors Richard Munang and Johnson Nkem advocate for community-based adaptation programs to increase resilience to food crises in the Horn of Africa. “Given that hunger and poverty are concentrated in rural areas,” the authors write, “targeting local food systems represents the single biggest opportunity to increase food production, boost food security, and reduce vulnerability.” The authors present a joint UNEP-UNDP adaptation initiative undertaken in Uganda as a framework for potential adaptation interventions in the Horn. They conclude that the initiative’s approach – pairing locally-focused sustainable farming techniques with a national-level emphasis on adaptation programs, and upscaling lessons learned from one level to the other – “will increase local buffering capacity against droughts, make communities more independent from direct aid, etc., build resilience and improve livelihoods overall.” -

Twin Challenges: Population and Climate Change in 2050

›

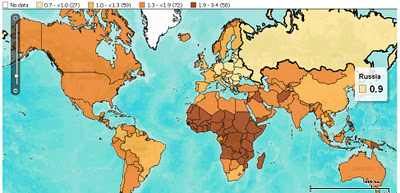

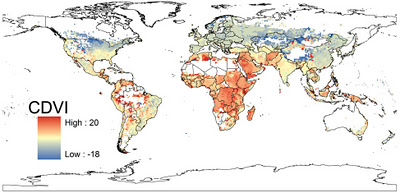

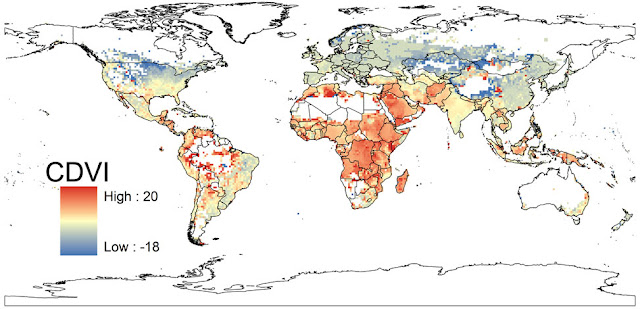

With global population reaching 7 billion, a lot of attention has been paid to the question of how to sustainably support so many people, much less the 9 billion expected by 2050, or the 10 billion possible by 2100. Add in the environmental variability projected from climate change and the outlook for supporting bigger and bigger populations gets even more problematic. Two new maps – one by the Population Reference Bureau (PRB), the other by McGill University PhD candidate Jason Samson – show how the world might change over the next 40 years in the face of these twin challenges.

With global population reaching 7 billion, a lot of attention has been paid to the question of how to sustainably support so many people, much less the 9 billion expected by 2050, or the 10 billion possible by 2100. Add in the environmental variability projected from climate change and the outlook for supporting bigger and bigger populations gets even more problematic. Two new maps – one by the Population Reference Bureau (PRB), the other by McGill University PhD candidate Jason Samson – show how the world might change over the next 40 years in the face of these twin challenges.

Nine Billion in 2050

PRB’s map, built using their DataFinder tool, shows the world in 2050 in terms individual country growth rates between now and then. Japan, Russia, and countries in Eastern Europe are set to grow more slowly than anywhere else, and some of that group will actually shrink by 10 to 20 percent of their current size. Western, Central, and Eastern Africa will be home to the highest increases. Niger’s 2050 population is expected to be 340 percent its 2011 size – the largest growth of any country.

The map is based on country-level data pulled from a number of sources: the UN Population Division’s latest “World Population Prospects,” the UN Statistics Division’s “Demographic Yearbook 2008,” the U.S. Census Bureau’s International Database, and PRB’s own estimates. It’s unclear what numbers come from which sources, though it is clear that PRB’s 2050 estimates span the UN’s range of medium, high, and constant-fertility variants. In spite of these variations, none of PRB’s estimates come anywhere near the UN Population Division’s low variant estimates.

PRB’s map, echoing its 2011 World Population Data Sheet, shows a world where sub-Saharan Africa will bear the brunt of population growth. The average country in Africa in 2050 is projected to be slightly more than twice its 2011 size; the average European country is expected to barely break even. Africa is home to more countries whose populations are estimated to least double (34) or triple (4) than any other continent. Europe, meanwhile, is home to more countries whose populations will stagnate (8), or even shrink (19), than anywhere else. Interestingly, the Caribbean is a close second in terms of countries whose populations are projected to stay the same (seven to Europe’s eight), and Asia is second to Europe in terms of countries whose populations are projected to shrink (Georgia, Japan, Armenia, South Korea, and Taiwan).

More People, More Climate Change, More Vulnerability

Samson’s map takes on the same time period but projects where people will be most vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Since his map takes into account population growth (measuring where people are most vulnerable, remember), unsurprisingly, Africa, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and central South America are covered in bright red dots, indicating high vulnerability. Conversely, North America, Europe, and much of Central Asia are in shades of blue.

Samson built his index using four environmental predictors – annual mean temperature, mean temperature diurnal range, total annual precipitation, and precipitation seasonality – taken from WorldClim’s 2050 forecasts, and 2005 sub-national population data from Columbia’s Center for International Earth Science Information Network. In spite of the sub-national population data, Samson makes a point to justify his use of supranational climate data in order to best reflect “the scale at which climate conditions vary.” He writes that localized issues like urbanization and coastal flooding “are probably best investigated with targeted regional models rather than by attempting to modify global models to include all factors of potential regional importance.”

Samson’s research shows that, generally, people living in places that are already hot will be more vulnerable to climate change over time, while people in more temperate climates will feel a negligible impact. Though he projects the largest real temperature changes will happen in temperate climates like North America and Europe, the comparatively smaller changes in Africa, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and central South America are expected to have a greater impact because those regions are already very hot, their natural resources are stressed, and they are expected to bear the brunt of population growth over the next few decades.

These findings reflect a disparity between those responsible for climate change and those bearing the brunt of it, which, although not surprising, “has important implications for climate adaptation and mitigation policies,” said Sampson, discussing the map in a McGill press release.

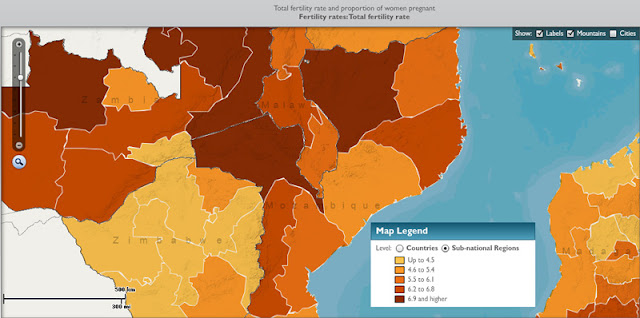

Sub-National Data “Present a Very Different Picture”

Though they offer a useful approximate glimpse at what the world might look at in 2050, both of these maps fall prey to over-aggregation. By looking at national rather than sub-national data, we miss how nuanced population growth rates can be within a country. Stimson Center Demographer-in-Residence Richard Cincotta wrote in a recent New Security Beat post that “national level comparisons of total fertility rates tend to communicate the false impression of a world with demographically homogeneous states.” Sub-national data, including differences between urban and rural areas and minority-majority fertility rates, “present a very different picture.”

And that difference matters. When it comes to looking at how population interacts with other issues, like the environment, poverty, and conflict, the importance of a sub-national approach becomes evident. In its 2011 data sheet, PRB writes that “poverty has emerged as a serious global issue, particularly because the most rapid population growth is occurring in the world’s poorest countries and, within many countries, in the poorest states and provinces.”

Edward Carr, an assistant geography professor at the University of South Carolina currently serving as a AAAS science fellow with USAID, argues that national-level data obscures our ability to understand food insecurity as well. The factors that drive insecurity “tend to be determined locally,” writes Carr in a post on his blog, and “you cannot aggregate [those factors] at the national level and get a meaningful understanding of food insecurity – and certainly not actionable information.”

The same is true when it comes to climate vulnerability. In a report from The Robert S. Strauss Center’s Climate Change and African Political Stability Program, authors Joshua Busby, Todd Smith, and Kaiba White write that “research announcing that ‘Africa is vulnerable to climate change,’ or even ‘Ethiopia is vulnerable,’ without explaining which parts of Ethiopia are particularly vulnerable and why, is of limited value to the international policy community.”

“It is of even less use to Africans themselves, in helping them prioritize scarce resources,” add Busby et al.

Understanding the joint problems of climate change and population growth on a global level helps frame the challenges facing the world as it moves toward 8, 9, and possibly 10 billion. But knowing the ins and outs of how these issues interact on a local level will be a necessary step before policymakers and others can hope to craft meaningful responses that minimize our vulnerability to these challenges over the coming decades.

Sources: Center for International Earth Science Information Network at Columbia University, Climate Change and African Political Stability Program at the Robert S. Strauss Center, McGill University, Population Reference Bureau, UN Population Division, UN Statistics Division, U.S. Census Bureau, University of South Carolina, WorldClim.

Image Credit: “2050 Population As a Multiple of 2011,” courtesy of PRB; CDVI map used with permission, courtesy of McGill University; Sub-national total fertility rates in Southern Africa, courtesy of MEASURE DHS, arranged by Schuyler Null.