Showing posts from category development.

-

Global Water Security Calls for U.S. Leadership, Says Intelligence Assessment

›March 26, 2012 // By Schuyler Null

Alongside and in support of Secretary Clinton’s announcement of a new State Department-led water security initiative last week was the release of a global water security assessment by the National Intelligence Council and Director of National Intelligence. The aim of the report? Answer the question: “How will water problems (shortages, poor water quality, or floods) impact U.S. national security interests over the next 30 years?”

-

Fourth World Water Development Report Released by UN

›The beginning of last week’s World Water Forum in Marseille also marked the release of UNESCO’s fourth edition of the World Water Development Report. Chief amongst the challenges outlined in the new report are meeting demand from growing population and consumption. Agriculture accounts for 70 percent of water usage, according to the report, and globally we will require 70 percent more food over the next 40 years, introducing the possibility of overtaxing already-stressed water resources – all while adapting to climate change. There are substantial gains to be had in increasing farm-to-table efficiency, especially in developing countries, the authors sagely point out, but the supply challenge remains a huge one.

This year’s edition also adds several new sections, including on women and water. “The crisis of scarcity, deteriorating water quality, the linkages between water and food security, and the need for improved governance are the most significant in the context of gender differences in access to and control over water resources,” write the authors. “These challenges are expected to become more intense in the future.”

The integrated nature of today’s water issues is a highlight throughout the report. “Accelerated change” will create new threats and “interconnected forces” create uncertainty and risk, but UNESCO emphasizes that if policymakers are made aware of these issues, ultimately “these forces can be managed effectively and can even generate vital opportunities and benefits through innovative approaches to allocation, use, and management of water.”

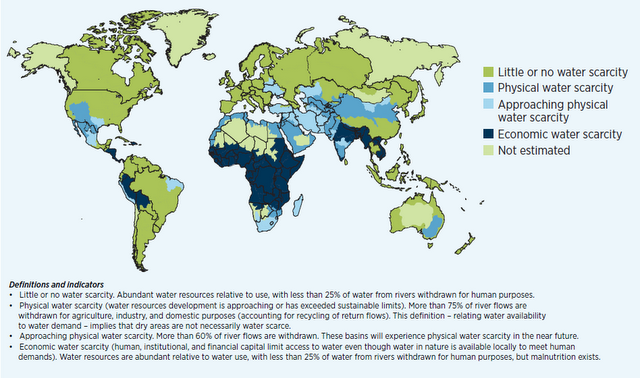

Image Credit: Water Management Institute, via figure 15.5 from UNESCO World Water Development Report. -

PBS ‘NewsHour’ and Pulitzer Center Examine Water Shortage and Health Issues in Ghana and Nigeria

› The PBS NewsHour continued its collaboration with the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting on international reporting last week with an episode on water infrastructure in Ghana and Nigeria. The coverage is especially apropos on World Water Day.

The PBS NewsHour continued its collaboration with the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting on international reporting last week with an episode on water infrastructure in Ghana and Nigeria. The coverage is especially apropos on World Water Day.

Correspondent Steve Sapienza spoke to reporters in Ghana and Nigeria to highlight long-running access and sanitation issues in both countries caused by poor infrastructure that has not kept up with growth.

Ameto Akpe is a local reporter for Nigeria’s BusinessDay, where her stories “target the contradiction of a country with immense oil wealth and great water resources that are not reaching their citizens.” In the city of Makurdi, capital of the north-central Benue State, she reports on the hundreds of thousands of people who rely on either high-priced water delivery or untreated water drawn straight from the Benue River.

“The previous attempt to build a water treatment plant ended in scandal in 2008,” says Sapienza, “with an unfinished treatment facility and city officials unable to account for $6 million.”

“Unfortunately, the waterworks is only half of the solution to Makurdi’s water problem,” writes Akpe on the Pulitzer Center. “The other half is a system of pipes to deliver the water to the people – and that project is just a twinkle in the eye of a handful of contractors and bureaucrats.”

In Ghana, metro TV reporter Samuel Agyemang explains similar access and sanitation issues in the capitol of Accra and its suburb of Teshie, where some residents have waited decades for piped water, despite substantial foreign investments.

The Pulitzer Center’s Peter Sawyer explains in a companion piece that “the population of Accra has grown enormously in the past several decades. But the water supply system has not grown with it.” As a result, the Ghana Water Company is constantly playing catch-up to provide water to communities, many of whom do not understand how to demand accountability from their officials, says Agyemang.

According to UN estimates, Ghana’s population has increased by more than 10 million people since 1990. Nigeria is one of the fastest growing countries in the world, with 158 million people currently and the UN medium projection estimating a possible 389 million by mid-century.

Reporter Ameto Akpe will be speaking about Nigeria’s water and sanitation problems at an upcoming all-day event on Nigeria at the Wilson Center, scheduled for April 25.

Sources: PBS NewsHour, Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting, UN Population Division. -

Food Security in a Climate-Altered Future, Part Two: Population Projections Are Not Destiny

›March 20, 2012 // By Kathleen MogelgaardRead part one, on the food-population-climate vulnerability dynamics of Malawi and other “hotspots,” here.

Too often, discussions about future food security make only a passing reference to population growth. It is frequently framed as an inevitable force, a foregone conclusion – and a single future number is reported as gospel: nine billion people in 2050. But adhering to a single path of future population growth misses the opportunity to think more holistically about food security challenges and solutions. Several recent food security reports illustrate this oft-overlooked issue.

Accounting for Population a Challenge

Oxfam International’s Growing a Better Future: Food Justice in a Resource-Constrained World is a thorough and fascinating examination of failures in our current food system and future challenges related to production, equity, and resilience. It reports newly-commissioned research, carried out by modelers at the Institute of Development Studies, to assess future agricultural productivity and food prices given the anticipated impacts of climate change.

But both the modeling work and the report text utilize a single projection for population growth: the UN’s 2008 medium variant projection of 9.1 billion by 2050 (which has since been revised by the UN up to 9.3 billion). Early on, the report does recognize some degree of uncertainty about this number: “Greater investment in solutions that increase women’s empowerment and security – by improving access to education and health care in particular – will slow population growth and achieve stabilization at a lower level.” But such investments do not appear in the report’s overall recommendations or Oxfam’s food security agenda. This is perhaps a missed opportunity, since the range of possibilities for future population growth is wide: the UN’s low variant for 2050 is 8.1 billion, and the high variant is 10.6 billion.

Food Security, Farming, and Climate Change to 2050: Scenarios, Results, and Policy Options is another frequently-cited report published by the International Food Policy Research Institute in 2010. In recognizing that economic growth and demographic change have important implications for future food security, IFPRI researchers modeled multiple scenarios for the future: an “optimistic” scenario which embodies high GDP growth and low population growth, a “pessimistic” scenario with low GDP growth and high population growth, and a “baseline” scenario which incorporates moderate GDP growth and the UN’s medium population projection. Each of these scenarios was then combined with five different climate change scenarios to better understand a range of possible futures.

Using different socioeconomic scenarios enabled researchers to better understand the significance of socioeconomic variables for future food security outcomes. The first key message from the report is that “broad-based economic development is central to improvements in human well-being, including sustainable food security and resilience to climate change.” This focus on economic development is based in part on the “optimistic scenario,” which counts on high GDP and low population growth (translating to high rates of per capita GDP growth).

Unfortunately, the socioeconomic scenario construction for this analysis doesn’t allow for an independent assessment of the significance of slower population growth, since high population growth is paired only with low GDP and lower population growth is paired only with high GDP. Therefore, none of the report’s recommendations includes reference to reproductive health, women’s empowerment, or other interventions that would contribute directly to a slower population growth path.

Expanding the Conversation to Better Inform Policy

Without a more nuanced treatment of population projections in technical analysis and popular reporting on food security, decision-makers in the realm of food security may not be exposed to the idea that population growth, a factor so critical in many areas where food security is already a challenge, is a phenomenon that is responsive to policy and programmatic interventions – interventions that are based on human rights and connected to well-established and accepted development goals.

There are some positive signs that this conversation is evolving. A new climate change, food security, and population model developed by the Futures Group enables policymakers and program managers to quickly and easily assess the impact of slower population growth on a country’s future food requirements and rates of childhood malnutrition. In the case of Ethiopia, for example, the model demonstrates that by 2050, a slower population growth path would make up for the caloric shortfall that is likely to arise from the impact of climate change on agriculture and would cut in half the number of underweight children.

And recently, we’ve begun to see some of this more nuanced treatment of population, family planning, and food security linkages in a riveting, year-long reporting series (though perhaps unfortunately named), Food for 9 Billion, a collaboration between American Public Media’s Marketplace, Homelands Productions, the Center for Investigative Reporting, and PBS NewsHour.

In January, reporter Sam Eaton highlighted the success of integrated population-health-environment programs in the Philippines, such as those initiated by PATH Foundation Philippines, that are seeing great success in delivering community-based programs that promote food security through a combination of fisheries management and family planning service delivery. Reporting from the Philippines in an in-depth piece for PBS NewsHour, Eaton concluded:So maybe solving the world’s food problem isn’t just about solving the world’s food problem. It’s also about giving women the tools they want, so they can make the decisions they want – here in the world’s poorest places.

Making clear connections of this nature between population issues and the most pressing challenges of our day may be the missing link that will help to mobilize the political will and financial resources to finally fully meet women’s needs for family planning around the world – an effort that, if started today, can have ongoing benefits that will become only more significant over time. Integrating reproductive health services into food security programs and strategies is an important start.

Back in Malawi, just before we turned off the highway to the Lilongwe airport, I asked the taxi driver to pull over in front of a big billboard. We both smiled as we looked at the huge government-sponsored image of a woman embracing an infant. The billboard proclaimed: “No woman should die while giving life. Everyone has a role to play.” Exactly. The reproductive health services that save women’s lives are the same services that can slow population growth and bring food security within closer reach. -

Food Security in a Climate-Altered Future, Part One: “Hotspots” Suggest Food Insecurity More Than a Supply Problem

›March 20, 2012 // By Kathleen MogelgaardSmall talk about the weather with my Malawian taxi driver became serious very quickly. “We no longer know when the rains are coming,” he said as we bumped along the road toward the Lilongwe airport last November. “It is very difficult, because we don’t know when to plant.”

These days, he is grateful for his job driving a taxi. His extended family and friends are among the 85 percent of Malawians employed in agriculture, much of which is small-holder, rain-fed subsistence farming. Weather-related farming challenges contribute to ongoing food insecurity in Malawi, where one in five children is undernourished.

His observations of the recent changes in climate match forecasts for the region: In East Africa, climate change is expected to reduce the productivity of maize – Malawi’s main subsistence crop – by more than 20 percent by 2030, according to a recent analysis by Oxfam International.

I looked out the window at dusty fields and tried to imagine what Malawi might look like in 2030. For one thing, it will be more crowded. A lot more crowded. According to UN population projections, by 2030, Malawi’s population will have grown from about 15 million today to somewhere between 26.9 and 28.4 million. With climate change dampening agricultural productivity and population growth increasing food demand, how will Malawians – many of whom don’t have enough to eat now – have enough to eat in the future?

It gets quiet in the taxi as the driver and I both ponder this question. Malawi is not alone in being a climate-vulnerable country with a rapidly growing population dependent on rain-fed agriculture. Population Action International’s Mapping Population and Climate Change tool shows us that many “hotspot” countries – scattered across Latin America, Africa, and Asia – face the triple challenge of low climate change resilience, projected decline in agricultural productivity, and rapid population growth.

Agricultural trade, government safety net programs, and foreign assistance will no doubt continue to play an important role in the quest for food security in Malawi and other “hotspot” countries in the future. And climate change adaptation projects will, hopefully, reshape agricultural practices and technologies in ways that can boost yields and enable crops to better withstand temperature and precipitation fluctuations.

These interventions will be critical in addressing the supply side of future food security challenges. But what about growing demand?

Malthus Revisited?

Juxtaposing population growth with food production does, of course, bring us back to Thomas Robert Malthus’ original (and by now somewhat infamous) dire warning: that population growth would eventually outrun food supply. But seeing the scale of the challenges in Malawi firsthand, I must admit that my inner Malthus sat up and took notice.

It is true that technological advances have enabled astounding growth in agricultural yields that have enabled us to feed the world in ways the doom-filled Malthus could never have imagined in the early 19th century. But it is also true that the agricultural productivity gains that helped us keep pace with population growth for so long are beginning to slow: According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, aggregate agricultural yields averaged 2.0 percent growth annually between 1970 and 1990, but that growth in yields declined to 1.1 percent between 1990 and 2007, and is projected to decline to less than 1.0 percent in the years to come.

This comes at a time when the Food and Agriculture Organization reports that food production will need to increase by 70 percent by 2050 in order to adequately feed a larger, wealthier, and more urbanized population.

To dismiss any talk of population growth as outmoded Malthusian hand-wringing misses an opportunity to embrace interventions that can contribute significantly to prospects for future food security – namely, empowering women with information and services that enable them to determine the timing and spacing of their children.

In Malawi and many of the “hotspot” countries around the world, high proportions of women remain disempowered in this regard. Meaningful access to family planning and reproductive health services results in smaller, healthier families that will be better equipped to cope with the food security challenges that are headed their way.

Not only does a smaller family mean that limited household resources go further, but access to family planning and reproductive health services is connected to other important education and economic outcomes.

A new Population Reference Bureau policy brief, for example, highlights how improving women’s reproductive health will not only lead to declining fertility and slower population growth in sub-Saharan Africa, but can also contribute to balancing a woman’s many roles (agricultural producer, worker, mother, caregiver, etc.) in ways that support greater food security for her family. And research by the International Food Policy Research Institute shows that in developing countries, women’s education and per capita food availability are the most important underlying determinants of child malnutrition – with women’s education having the strongest beneficial impact. Access to family planning paves the way for these outcomes – and by slowing population growth, can help to slow the growth in food demand.

Women’s Needs and Future Food Demand

The scale of potential benefits of meeting women’s family planning needs is significant when thinking about future food demand, both globally and especially in food insecure, climate-vulnerable countries. As we have seen in Malawi, there is a range of possible future population sizes and that range grows even wider when the projections are extended to 2050: According to the UN, Malawi’s 15 million today will grow to somewhere between 45 million and 55 million by 2050.

That span of 10 million people embodies assumptions about declining fertility in Malawi. To reach 55 million, the average number of children per woman would need to drop from 5.7 today to 4.5 by 2050. If fertility drops further, to 3.5 children per woman, Malawi’s population would grow to (only) 45 million. Where Malawi ends up in that 10-million-person population spread will have deep implications for per capita food availability, not to mention other important development outcomes.

Fertility declines of this kind do not require coercion or “population control.” As we have seen time and again, when women are empowered with information and services that enable them to determine the timing and spacing of their children, smaller, healthier families are the inevitable result.

Meeting women’s needs for reproductive health and family planning services is not – and never should be – about reducing population size. Universal access to reproductive health is recognized as a basic human right and central development goal (embodied in Millennium Development Goal 5) because of its vital connections to women’s and children’s health, education and employment opportunities, and poverty alleviation. And yet, too many women remain without the ability to effectively plan their families. In Malawi, one in four married women would like to delay their next birth or end child-bearing all together but aren’t using contraception; globally, 215 million have this unmet need.

As global efforts ramp up to address interlinked challenges of food security and climate change adaptation, assessing the role of population growth is more important than ever. And in designing strategies to address these challenges – strategies like the U.S. Government’s Feed the Future Initiative and UN-supported National Adaptation Plans – we should not pass over opportunities to incorporate interventions to close the remaining gap in universal access to family planning, especially in places like Malawi and other “hotspot” countries (such as Haiti, Nigeria, and Nepal), where women’s unmet family planning needs are high and population growth is rapid.

Continue reading with part two on the often under-examined role of population projections in food security assessments here.

Sources: Food and Agriculture Organization, Guttmacher Institute, International Food Policy Research Institute, International Institute for Environment and Development, MEASURE DHS, Oxfam International, Population Action International, Population Reference Bureau, The Lancet, U.S. Department of Agriculture, UN Population Division.

Photo Credit: Women in a village near Lake Malawi make cornbread while caring for small children, used with permission courtesy of Jessica Brunacini. -

Lakis Polycarpou, State of the Planet

Finding the Link Between Water Stress and Food Prices

›March 19, 2012 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Lakis Polycarpou, appeared on State of the Planet.

Over the past decade, average global food prices have more than doubled, with 2008 and 2010 seeing excruciating price spikes that each had far-reaching economic, geopolitical, and social consequences.

What explains this long-term trend – and why did prices spike so much higher in the years that they did?

For policymakers at all levels, answering that question is of vital importance if there is to be any hope of feeding the world’s growing population in the coming decades, much less maintaining social order.

According to recent research by the New England Complex Systems Institute, spikes in food prices are so closely correlated with social unrest that they were able to identify a particular food-price threshold above which food riots are very likely.

The most obvious cause for high food prices is oil – in fact, charts showing the correspondence between food and oil prices show an eerie overlap, especially in the last half decade. Water scarcity and climate are major players as well, however. According to the just released United Nations World Water Development Report, demand for water will grow by 55 percent in the next 40 years, and farmers will need 19 percent more water by 2050 just to keep up with growing food demands.

Continue reading on State of the Planet.

Sources: Nature, New England Complex Systems Institute, UNESCO.

Photo Credit: “Farmers work on the arid land in Hertela village few kilometers from Mahoba in Bundelkhand, India on September 26, 2008.” Courtesy of flickr user balazsgardi. -

John Williams: Helping People and Preserving Biodiversity Hotspots

›March 16, 2012 // By Schuyler Null“Both humans and the number of species in the world are not evenly distributed across the globe,” said John Williams of the University of California, Davis, who recently spoke at the Wilson Center about his contribution to Biodiversity Hotspots: Distribution and Protection of Conservation Priority Areas. “In particular we find that species diversity is concentrated in what’s called the biodiversity ‘hotspots.’”

Largely in the tropics, Mediterranean climates, and along mountain chains, biodiversity hotspots are “where there’s a real concentration in number of species and also unique species – plants and animals that exist nowhere else on Earth,” he said.

“It’s a very complex relationship between biodiversity and human population, because it’s not necessarily [true] that places of high human population are a threat to biodiversity,” said Williams. Many different factors play a role, “like education, like consumption, like economic development, different cultures – how people interface with the natural world – all these things create nuances as far as what that relationship is between biodiversity and where people live.”

“There are some basic things we can do that are going to be good for human welfare, as well as biodiversity,” he continued. A few are addressing lack of education, especially among girls, in areas of high biodiversity; providing basic health services, including family planning, where rural growth rates are highest; and improving physical access to rural areas to promote economic development.

“We see there’s a direct correlation between each additional year of schooling a girl has and their fertility during their lifetime,” Williams said. “As people climb out of poverty, they also choose to have smaller, healthier families.” -

Kavita Ramdas: Why Educating Girls Is Not Enough

› “I’m a big proponent of girl’s education. I believe that it’s a very important and a very valuable human rights obligation that all countries should be meeting,” said Kavita Ramdas, executive director for programs on social entrepreneurship at Stanford University, at the Wilson Center. However, “in the past seven to eight years we have found ourselves in a situation where there’s kind of an enchantment with girl’s education, as though it were the new microenterprise magic bullet to solve everything from poverty, to malnourishment, to inequality.”

“I’m a big proponent of girl’s education. I believe that it’s a very important and a very valuable human rights obligation that all countries should be meeting,” said Kavita Ramdas, executive director for programs on social entrepreneurship at Stanford University, at the Wilson Center. However, “in the past seven to eight years we have found ourselves in a situation where there’s kind of an enchantment with girl’s education, as though it were the new microenterprise magic bullet to solve everything from poverty, to malnourishment, to inequality.”

“The outcomes that we ascribe to girl’s education…are not anything that I would argue with,” she said, yet, this enchantment “has happened simultaneously with a significant drop in both funding and support for strategies that give girls and women access to reproductive health and choices, particularly family planning.”

This is a problem, said Ramdas, because we cannot rely on education alone to do all the heavy lifting required to empower women.

“I think it’s important for us to recognize that there are societies where girls and women have achieved significantly high levels of education in which gender inequality remains,” she said, “for example, places like Japan and Saudi Arabia, where you have high per capita income, high levels of education, and yet…where women and girls are still marginalized and on the edges in terms of decision making.”

“I don’t think we have to wait for one to be able to do the other,” she said. “As we support programs for girls’ education, we also need to demand that those programs be buttressed by strong programs in adolescent health, strong programs in sex education, strong programs that actually provide girls and women with access to family planning and contraception.”