Showing posts from category agriculture.

-

Food Production Goes Global, Sparking Land Grabs in Developing World

›December 8, 2008 // By Will Rogers As global food prices soar and population growth and urbanization shrink the supply of arable land, many countries have been forced to adopt new forms of production to secure their food supply. But instead of embracing sustainable land-use practices and improving rural development, some nations have shifted food production overseas, igniting a massive land grab in the developing world.

As global food prices soar and population growth and urbanization shrink the supply of arable land, many countries have been forced to adopt new forms of production to secure their food supply. But instead of embracing sustainable land-use practices and improving rural development, some nations have shifted food production overseas, igniting a massive land grab in the developing world.

From the Persian Gulf to East Asia, governments and international companies alike have been lobbying developing countries in Africa and Asia to produce grain for food and alternative energy. The Guardian reported on November 22nd that Qatar recently leased 40,000 hectares of Kenyan farmland in return for funding a £2.4 billion port on the island of Lamu, a popular tourist site just off the Kenyan coast. The Saudi Binladen Group is said to be finalizing a deal with Indonesia to lease land for basmati rice production, while other Arab investors, including the Abu Dhabi Fund for Development, have bought land rights for agricultural production in Sudan and Pakistan. Ethiopian Prime Minister Meles Zenawi has been “courting would-be Saudi investors,” despite his country’s own deplorable food insecurity and chronic malnutrition.

Meanwhile, the Telegraph reported that South Korea’s Daewoo Logistics has been working to secure a 99-year lease for 3.2 million hectares of farmland in Madagascar that it will use to “grow 5 million metric tons of maize a year and 500,000 tons of palm oil” to use as biofuel in South Korea. The company says it expects to pay almost nothing besides infrastructure costs and employment training in return for its use of the land. Despite Madagascar’s rapid population growth and pervasive food insecurity, the deal, if signed, will allow the South Korean company to lease approximately half of the current arable farmland on the island state.

In an effort to combat a freshwater shortage, China has secured an agreement with Laos for a 50-year lease of 1,600 hectares of land in return for funding a new sports complex in Vientiane for the 2009 Southeast Asian Games. And with only 8 percent of the world’s arable land and more than one-fifth of the world’s population to feed, China continues to encourage its businesses to go outside China to produce food, looking to developing countries in Africa and Latin America.

Jacques Diouf, director-general of the UN Food and Agricultural Organization, recently warned that these deals are a “political hot potato” that could prove devastating to the developing world’s own food supply, as several of these states already face severe food insecurity. Diouf has expressed concern that these deals could breed a “neo-colonial” agricultural system that would have the world’s poorest and most malnourished feeding the rich at their own expense.

And with land rights a contentious issue throughout the developing world—including in Haiti, Kenya, and Sudan, for instance—these agreements could spark civil conflict if governments and foreign investors fail to strike equitable deals that also benefit local populations. “Land is an extremely sensitive thing,” warns Steve Wiggins, a rural development expert at the Overseas Development Institute. “This could go horribly wrong if you don’t learn the lessons of history” and attempt to minimize inequality.

As food prices continue to climb, more and more countries are likely to scramble to gain access to the developing world’s arable land. Without land-use agreements that ensure a host country’s domestic food supply is secure before its foreign investor’s, long-term sustainable development could be set back decades, something impoverished developing countries simply cannot afford.

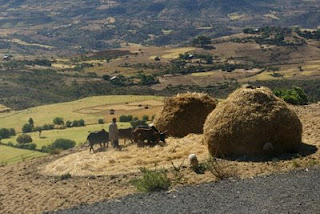

Photo: A man threshing in Ethiopia. Long plagued by acute food insecurity, Ethiopia’s arable land is sought by more-developed countries to ensure the stability of their own food stocks. Courtesy of Flickr user Eileen Delhi. -

Weekly Reading

›Military leaders and climate experts gathered in Paris for a November 3-5 conference on the role of the military in combating climate change. A conference report will include “proven strategies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions while improving military effectiveness.”

The 2008 Africa Population Data Sheet, a joint project of the Population Reference Bureau and the African Population and Health Research Center, reveals significant differences between northern and sub-Saharan Africa. Also from PRB, “Reproductive Health in Sub-Saharan Africa” examines family planning use, family size, maternal mortality, and HIV/AIDS in major subregions of sub-Saharan Africa.

In the October 2008 issue of Humanitarian Exchange Magazine, Alexander Tyler of the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees for Somalia argues that longer-term livelihoods projects must be incorporated into emergency humanitarian relief efforts. The authors of the Center for American Progress report The Cost of Reaction: The Long-Term Costs of Short-Term Cures (reviewed on the New Security Beat) would likely agree; they argue that although emergency aid is necessary, “what is true in our own lives is true on the international stage—an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.”

The Dining & Wine section of the New York Times profiles a Quichua community in the Ecuadorian Amazon that has formed a successful chocolate cooperative with the help of a volunteer for a biodiversity foundation. “They wanted to find a way to survive and thrive as they faced pressure from companies that sought to log their hardwood trees, drill on their land for oil and mine for gold,” reports the Times. -

United Nations Observes International Day for Preventing the Exploitation of the Environment in War and Armed Conflict

›November 6, 2008 // By Rachel Weisshaar Each November 6, the International Day for Preventing the Exploitation of the Environment in War and Armed Conflict passes by, largely unnoticed. But as the UN General Assembly noted in 2001 when it gave the day official status, “damage to the environment in times of armed conflict”—including poisoning of water supplies and agricultural land; habitat and crop destruction; and damage resulting from the use of biological, chemical, and nuclear weapons—“impairs ecosystems and natural resources long beyond beyond the period of conflict, and often extends beyond the limits of national territories and the present generation.”

Each November 6, the International Day for Preventing the Exploitation of the Environment in War and Armed Conflict passes by, largely unnoticed. But as the UN General Assembly noted in 2001 when it gave the day official status, “damage to the environment in times of armed conflict”—including poisoning of water supplies and agricultural land; habitat and crop destruction; and damage resulting from the use of biological, chemical, and nuclear weapons—“impairs ecosystems and natural resources long beyond beyond the period of conflict, and often extends beyond the limits of national territories and the present generation.”

In a written statement issued today, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon points out that although natural resources are often exploited during war, they are also essential to establishing peace:The environment and natural resources are crucial in consolidating peace within and between war-torn societies. Several countries in the Great Lakes Region of Africa established trans-boundary cooperation to manage their shared natural resources. Lasting peace in Darfur will depend in part on resolving the underlying competition for water and fertile land. And there can be no durable peace in Afghanistan if the natural resources that sustain livelihoods and ecosystems are destroyed.

As the Development Gateway Foundation’s Environment and Development Community emphasizes, “[e]nvironmental security, both for reducing the threats of war, and in successfully rehabilitating a country following conflict, must no longer be viewed as a luxury but needs to be seen as a fundamental part of a long lasting peace policy.”

Some of the United Nations’ most important contributions to illuminating the links between conflict and environmental degradation are the excellent post-conflict environmental assessments that the UN Environment Programme’s (UNEP) Disasters and Conflicts Programme has carried out in Afghanistan, Lebanon, and Sudan, among other countries. UNEP is currently preparing to conduct an assessment of Rwanda’s environment.

Photo: A Kuwaiti oil field set afire by retreating Iraqi troops burns in the distance beyond an abandoned Iraqi tank following Operation Desert Storm. Courtesy of Flickr user Leitmotiv. -

Prostitution, Agriculture, Development Fuel Human Trafficking in Brazil

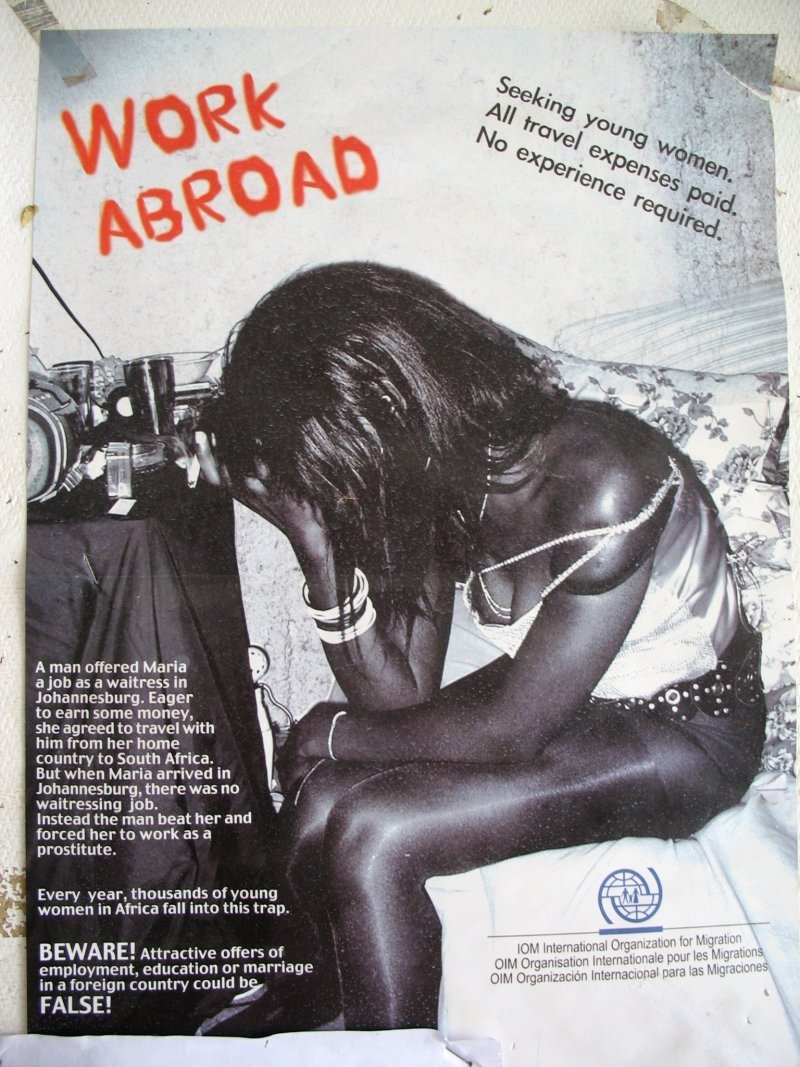

›October 28, 2008 // By Ana Janaina NelsonModern-day slavery, also known as human trafficking, is the third most lucrative form of organized crime in the world, after trade in illegal drugs and arms trafficking. Today, 27 million people are enslaved—mostly as a result of debt bondage. The UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) report Trafficking in Persons: Global Patterns found that Brazil is the third-largest source of human trafficking in the Western hemisphere, after Mexico and Colombia. According to the U.S. Department of State’s Trafficking in Persons Report 2008, 250,000-500,000 Brazilian children are currently exploited for prostitution, both domestically and abroad. NGOs estimate that 75,000 Brazilian women and girls—most of them trafficked—work as prostitutes in neighboring South American countries, the United States, and Europe.

In addition, notes the Trafficking in Persons Report 2008, 25,000-100,000 Brazilian men are forced into domestic slave labor. “Approximately half of the nearly 6,000 men freed from slave labor in 2007 were found exploited on plantations growing sugar cane for the production of ethanol, a growing trend,” says the report. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), the “agricultural states of the north, like Piaui, Maranhao, Pará and Mato Grosso, are the most problematic.” Agriculture and development have also been linked to sex trafficking. A 2003 study by the Brazilian NGO CECRIA found that in the Amazon, sexual exploitation of children often occurs in brothels that cater to mining settlements. The study also highlighted the prevalence of sex trafficking in regions with major development projects.

In response to growing awareness of the magnitude of this problem, the Brazilian Ministry of Justice has stepped up its efforts to combat human trafficking, adopting the ILO and UNODC’s “three-P” approach: prevention, prosecution, and protection. Prevention measures in Brazil focus on sexual exploitation, the most common type of forced labor for trafficked Brazilians. These measures include educating vulnerable populations about avoiding human trafficking, as well as drawing tourists’ attention to criminal penalties under Brazilian law for patronizing prostitutes.

Prosecution efforts in Brazil are also improving: In 2004, Brazil ratified the Palermo Protocol (pdf), the main international legal instrument for combating human trafficking. A year later, the country adopted a National Plan to Combat Human Trafficking, which aims to train those responsible for prosecuting traffickers and protecting victims—primarily police and judges. In addition, notes the Trafficking in Persons Report 2008:The Ministry of Labor’s anti-slave labor mobile units increased their operations during the year, as the unit’s labor inspectors freed victims, forced those responsible for forced labor to pay often substantial amounts in fines and restitution to the victims, and then moved on to others locations to inspect. Mobile unit inspectors did not, however, seize evidence or attempt to interview witnesses with the goal of developing a criminal investigation or prosecution because inspectors and the labor court prosecutors who accompany them have only civil jurisdiction. Because their exploiters are rarely punished, many of the rescued victims are ultimately re-trafficked.

The U.S. Department of State established a four-tiered assessment system to rate countries’ compliance with international trafficking mandates. In 2006, Brazil was listed on the Tier 2 Special Watch List, the second-worst rating, despite recognition that the government made “significant efforts” to combat human trafficking. Brazil recently moved into the Tier 2 category, however, due to more concerted interagency efforts, as well as greater compliance with international guidelines. Yet one wonders whether Brazil will be able to achieve Tier 1 status any time soon, given the Brazilian government’s focus on biofuel- and agriculture-fueled economic growth and the fact that the global financial crisis is likely to drive people into increasingly desperate economic straits.

By Brazil Institute Intern Ana Janaina Nelson.

Photo: A poster warns African women of the dangers of human trafficking; Brazilian women are subject to similar dangers. Courtesy of Flickr user mvcorks. -

A Roadmap for Future U.S. International Water Policy

› When I tell people I have been working on a report about U.S. international water policy, they usually respond with the same sardonic question: “The United States has an international water policy?” The answer, of course, is complicated. Yes, we have localized approaches to water challenges in parts of the developing world, and we have more than 15 government agencies with capacities to address water and sanitation issues abroad. And yes, the State Department and the U.S. Agency for International Development published a joint strategic framework this year for action on water issues in the developing world.

When I tell people I have been working on a report about U.S. international water policy, they usually respond with the same sardonic question: “The United States has an international water policy?” The answer, of course, is complicated. Yes, we have localized approaches to water challenges in parts of the developing world, and we have more than 15 government agencies with capacities to address water and sanitation issues abroad. And yes, the State Department and the U.S. Agency for International Development published a joint strategic framework this year for action on water issues in the developing world.

However, the U.S. government (USG) does not yet have an overarching strategy to guide our water programs abroad and maximize synergies among (and within) agencies. Furthermore, the 2005 Senator Paul Simon Water for the Poor Act—which calls for increased water and sanitation assistance to developing countries—has yet to be funded and implemented in a fashion that satisfies lawmakers. In fact, just last week, legislation was introduced in both the House and the Senate to enhance the capacity of the USG to fully implement the Water for the Poor Act.

Why has implementation been so slow? An underlying problem is that water still has no institutional home in the USG, unlike other resources like agriculture and energy, which have entire departments devoted to them. In the current system, interagency water coordination falls on a small, under-resourced (yet incredibly talented and dedicated) team in the State Department comprised of individuals who must juggle competing priorities under the broad portfolio of Oceans, Environment, and Science. In part, it is water’s institutional homelessness that hinders interagency collaboration, as mandates and funding for addressing water issues are not always clearly delineated.

So, what should be done? For the last year and a half, the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ (CSIS) Global Strategy Institute has consulted with policy experts, advocates, scientists, and practitioners to answer this million-dollar question. In our report, Global Water Futures: A Roadmap for Future U.S. Policy, we conclude that if we are serious about achieving a range of our strategic national interests, water must be elevated as a priority in U.S. foreign policy. Water is paramount to human health, agricultural and energy production, education, economic development, post-conflict stabilization, and more—therefore, our government’s organizational structure and the resources it commits to water should reflect the strategic importance of this resource.

Studies’ (CSIS) Global Strategy Institute has consulted with policy experts, advocates, scientists, and practitioners to answer this million-dollar question. In our report, Global Water Futures: A Roadmap for Future U.S. Policy, we conclude that if we are serious about achieving a range of our strategic national interests, water must be elevated as a priority in U.S. foreign policy. Water is paramount to human health, agricultural and energy production, education, economic development, post-conflict stabilization, and more—therefore, our government’s organizational structure and the resources it commits to water should reflect the strategic importance of this resource.

We propose the creation of a new bureau or “one-stop shop” for water policy in the State Department to lead in strategic planning, implementation, and evaluation of international water programs; mobilize resources in support of water programming overseas; provide outreach to Congress and important stakeholders; and serve as a research and information clearinghouse. This would require significant support from the highest levels of government, increased funding, and greater collaboration with the private and independent sectors.

The current economic crisis means we are likely to face even greater competition for scarce foreign aid resources. But I would argue—paraphrasing Congressman Earl Blumenauer at our report rollout—that relatively little funding toward water and sanitation can have a significant impact around the world. As we tighten our belts during this period of financial instability, it is even more important that we invest in cross-cutting issues that yield the highest returns across defense, development, and diplomacy. Water is an excellent place to start.

Rachel Posner is a research associate at the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Global Strategy Institute.

Photo: Environmental Change and Security Program Director Geoff Dabelko and Congressman Earl Blumenauer (D-OR) at the launch of Global Water Futures: A Roadmap for Future U.S. Policy. Courtesy of CSIS. -

Senators McCain, Obama Announce Priorities for Alleviating Poverty, Tackling Climate Change at Clinton Global Initiative

›September 25, 2008 // By Rachel WeisshaarSpeaking at a Clinton Global Initiative plenary session (webcast; podcast) this morning, Senator John McCain (R-AZ) and Senator Barack Obama (D-IL) laid out their proposals for addressing the interconnected problems of global poverty, climate change, and disease. Excerpts from each senator’s speech are below.

Senator McCain:

“We can never guarantee our security through military means alone. True security requires a far broader approach using non-military means to reduce threats before they gather strength. This is especially true of our strategic interests in fighting disease and extreme poverty across the globe.”

“Malaria alone kills more than a million people a year, mostly in Africa….To its lasting credit, the federal government in recent years has led the way in this fight. But of course, America is more than its government. Some of the greatest advances have been the work of the Gates Foundation and other groups. And you have my pledge: Should I be elected, I will build on these and other initiatives to ensure that malaria kills no more. I will also make it a priority to improve maternal and child health. Millions around the world today—and especially pregnant women and children—suffer from easily prevented nutritional deficiencies….An international effort is needed to prevent disease and developmental disabilities among children by providing nutrients and food security. And if I am elected president, America will lead that effort, as we have done with the scourge of HIV and AIDS.”

“America helped to spark the Green Revolution in Asia, and…[we] should be at the forefront of an African Green Revolution. We should and must reform our aid programs to make sure they are serving the interests of people in need, and not just serving special interests in Washington. Aid’s not the whole answer, as we know. We need to promote economic growth and opportunities, especially for women, where they do not currently exist. Too often, trade restrictions, combined with costly agricultural subsidies for the special interests, choke off the opportunities for poor farmers and workers abroad to help themselves. That has to change.”

Senator Obama:

“Our security is shared as well. The carbon emissions in Boston or Beijing don’t just pollute the immediate atmosphere, they imperil our planet. Pockets of extreme poverty in Somalia can breed conflict that spills across borders. The child who goes to a radical madrassa outside of Karachi can end up endangering the security of my daughters in Chicago. And the deadly flu that begins in Indonesia can find its way to Indiana within days. Poverty, climate change, extremism, disease—these are issues that offend our common humanity. They also threaten our common security….We must see that none of these problems can be dealt with in isolation; nor can we deny one and effectively tackle another.”

“Our dependence on oil and gas funds terror and tyranny. It’s forced families to pay their wages at the pump, and it puts the future of our planet in peril. This is a security threat, an economic albatross, and a moral challenge of our time.”

“As we develop clean energy, we should share technology and innovations with the nations of the world. This effort to confront climate change will be part of our strategy to alleviate poverty because we know that it is the world’s poor who will feel—and may already be feeling—the effect of a warming planet. If we fail to act, famine could displace hundreds of millions, fueling competition and conflict over basic resources like food and water. We all have a stake in reducing poverty….It leads to pockets of instability that provide fertile breeding-grounds for threats like terror and the smuggling of deadly weapons that cannot be contained by the drawing of a border or the distance of an ocean. And these aren’t simply disconnected corners of an interconnected world. And that is why the second commitment that I’ll make is embracing the Millennium Development Goals, which aim to cut extreme poverty in half by 2015. This will take more resources from the United States, and as president, I will increase our foreign assistance to provide them.”

“Disease stands in the way of progress on so many fronts. It can condemn populations to poverty, prevent a child from getting an education, and yet far too many people still die of preventable illnesses….When I am president, we will set the goal of ending all deaths from malaria by 2015. It’s time to rid the world of a disease that doesn’t have to take lives.” -

Drought, War, Refugees, Rising Prices Threaten Food Security in Afghanistan

›September 23, 2008 // By Rachel WeisshaarDrought, continuing violence, returning refugees, and the spike in global food prices are combining to produce a serious threat to Afghan food security, reports the New York Times. The World Food Program has expanded its operations in Afghanistan to cover a total of nearly 9 million people through the end of next year’s harvest, sending out an emergency appeal to donors to cover the costs.

According to a report published earlier this year by Oxfam UK,[W]ar, displacement, persistent droughts, flooding, the laying of mines, and the sustained absence of natural resource management has led to massive environment degradation and the depletion of resources. In recent years Afghanistan’s overall agricultural produce has fallen by half. Over the last decade in some regions Afghanistan’s livestock population has fallen by up to 60% and over the last two decades, the country has lost 70% of its forests.

A post-conflict environment assessment conducted by the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) in 2003 confirms these dire trends in further detail. “In some areas, we found that up to 95 percent of the landscape had been deforested during the conflict—cut for fuel, bombed to remove cover, or removed to grow crops and graze livestock. Many people were fundamentally dependant on these forests for livelihoods. Without them, and without alternatives, Afghans were migrating to the cities or engaging in other forms of income generation—such as poppy production for the drug trade—in order to survive,” writes UNEP’s David Jensen in a forthcoming article in ECSP Report 13.

Despite the fact that agriculture has traditionally employed or supported approximately 80 percent of Afghans, says Oxfam, donors have vastly underinvested in the sector, spending only $300-400 million over the past six years directly on agricultural projects—a sliver of overall aid to Afghanistan.

Not only does hunger have negative impacts on health and economic growth, it could also make the security situation worse. “Development officials warn that neglecting [agriculture and development in] the poorest provinces can add to instability by pushing people to commit crimes or even to join the insurgency, which often pays its recruits,” reports the Times. In addition, an Oxfam International survey of six Afghan provinces found that land and water were the top two causes of local disputes.

To head off greater food insecurity and potential threats to overall stability, Oxfam UK recommends the development of a comprehensive national agricultural program; improved land and water management capacities; and greater support for non-agricultural income-generating activities, such as carpet-making.

Photo: An irrigated area near Kunduz, in northern Afghanistan. Courtesy of UN Environment Programme (source: Afghanistan Post-Conflict Environmental Assessment). -

Weekly Reading

›A report from the Center for Strategic and International Studies argues that the global food crisis poses a moral and humanitarian threat; a developmental threat; and a strategic threat. The authors recommend that the United States: modernize emergency assistance; make rural development and agriculture top U.S. foreign policy priorities; alter the U.S. approach to biofuels; ensure U.S. trade policy promotes developing-country agriculture; and strengthen relevant U.S. organizational capacities.

In an article in Scientific American, Jeffrey Sachs argues that the global food shortages Thomas Malthus predicted in 1798 may still come to pass if we do not slow population growth and begin using natural resources more sustainably.

A report by the Government Accountability Office finds that food insecurity in sub-Saharan African persists, despite U.S. and global efforts to halve it by 2015, due to “low agricultural productivity, limited rural development, government policy disincentives, and the impact of poor health on the agricultural workforce. Additional factors, including rising global commodity prices and climate change, will likely further exacerbate food insecurity in the region.”

In an article in the Belgian journal Les Cahiers du Réseau Multidisciplinaire en Etudes Stratégiques, Thomas Renard argues that climate change is likely to increase the risk of environmental terrorism (attacks that use the environment as a tool or target), eco-terrorism (attacks perpetrated on behalf of the environment), nuclear terrorism, and humanitarian terrorism (attacks targeting humanitarian workers).

A Community Guide to Environmental Health, available for free online in PDF, is a field-tested, hands-on guide to community-based environmental health. Topics include waterborne diseases; sustainable agriculture; mining and health; and using the legal system to fight for environmental rights.

As global food prices soar and population growth and urbanization shrink the supply of arable land, many countries have been forced to adopt new forms of production to secure their food supply. But instead of embracing sustainable land-use practices and improving rural development, some nations have shifted food production overseas, igniting a massive land grab in the developing world.

As global food prices soar and population growth and urbanization shrink the supply of arable land, many countries have been forced to adopt new forms of production to secure their food supply. But instead of embracing sustainable land-use practices and improving rural development, some nations have shifted food production overseas, igniting a massive land grab in the developing world. Each November 6, the International Day for Preventing the Exploitation of the Environment in War and Armed Conflict passes by, largely unnoticed. But as the UN General Assembly noted in 2001 when it gave the day official status, “damage to the environment in times of armed conflict”—including poisoning of water supplies and agricultural land; habitat and crop destruction; and damage resulting from the use of biological, chemical, and nuclear weapons—“

Each November 6, the International Day for Preventing the Exploitation of the Environment in War and Armed Conflict passes by, largely unnoticed. But as the UN General Assembly noted in 2001 when it gave the day official status, “damage to the environment in times of armed conflict”—including poisoning of water supplies and agricultural land; habitat and crop destruction; and damage resulting from the use of biological, chemical, and nuclear weapons—“

When I tell people I have been working on a report about U.S. international water policy, they usually respond with the same sardonic question: “The United States has an international water policy?” The answer, of course, is complicated. Yes, we have localized approaches to water challenges in parts of the developing world, and we have

When I tell people I have been working on a report about U.S. international water policy, they usually respond with the same sardonic question: “The United States has an international water policy?” The answer, of course, is complicated. Yes, we have localized approaches to water challenges in parts of the developing world, and we have  Studies’ (CSIS)

Studies’ (CSIS)