-

Taking the Slow Lane to Green Transition in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor

July 24, 2025 By Hong ZhangPakistan’s summer sun is relentless, but its golden rays may hold a promising clean energy solution.

During my visit to that country last summer, an energy sector expert I met expressed amazement that Pakistan had imported 13 gigawatts of solar modules from China in the first six months of 2024. Media reports celebrated how even remote villages were adopting rooftop solar systems. International observers lauded Pakistan’s “stunning solar boom.”

Pakistan and China have been cooperating under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) agreement for almost a decade now. It once was hailed as a “game changer” for Pakistan’s economy. Yet the agreement has been marred by financial troubles and security concerns for years.

In an effort to revive the bilateral initiative, leaders from both countries presented an “upgraded version” with a new “green corridor” in October 2024, opening the door for solar to become the next big investment in CPEC.

Taking a closer look at CPEC’s trajectory paints a more pessimistic picture. Chinese investments have expanded Pakistan’s energy capacity, but also left a legacy of coal-fired power plants. This heavy reliance on coal and misaligned energy policies have hindered solar power. Thus, China now must learn from this failure—and align its future investments with Pakistan’s actual renewable energy (RE) potential.

Coal-heavy Investment Misses Renewable Potential

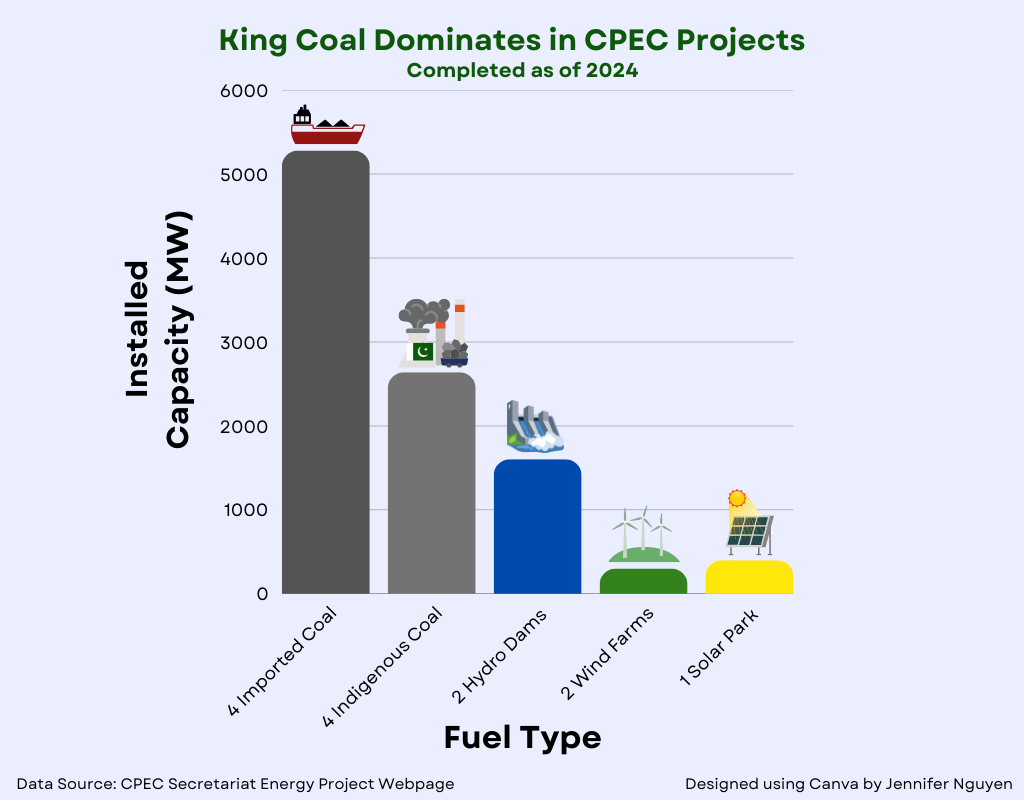

Power sector investment was a key focus when CPEC launched in 2013. Fully 14 power generation projects (9,000 MW) valued over $15 billion were built by 2024, and over 70% of them were coal-fired—with more than half relying on imported coal.

CPEC investments raised the share of coal power from just over 3% in 2017 to over 19% in 2024. A 2019 study attributed this coal-heavy mix to both China’s “push” for exporting coal power capacity and Pakistan’s “pull” for cheaper and faster power.

While renewable energy costs have dropped precipitously, the 700 megawatts (MW) from one solar PV and four wind power projects accounts for less than 8% of the total added capacity under CPEC.

So why wasn’t renewable energy prioritized in CPEC’s early planning? It wasn’t due to a lack of recognition of its potential.

Indeed, Pakistan enacted a Renewable and Alternative Energy Development Plan in 2006, offering incentives including a predetermined “feed-in tariff” (or “FiT,” which represents a guaranteed per-unit payment for the electricity generated). By the late 2010s, the Pakistani government also issued Letters of Intent (“LOIs,” or permits for prospective investors to proceed with a proposed project) for an estimated 8,000 MW of renewable energy.

As solar and wind costs rapidly declined, however, the FiTs based on prior prevailing costs became overly generous. In 2017, Pakistan tried to replace them with competitive bidding, leading to uncertainty for investors who had already secured LOIs. Many investors urged the government to honor prior commitments, but an appropriate mechanism for tariff determination remained elusive.

For instance, the sole solar PV project under CPEC, Quaid-e-Azam Solar Park, initially included a planned, currently delayed, second 600 MW phase. Pakistan’s withdrawal of the approved FiT in 2016, however, compelled the project’s Chinese developer to resort to litigation. No resolution had been reached by 2024. Another Chinese company, China Three Gorges South Asia Investment Limited, failed to reinstate its LOI for a 100 MW solar project.

These situations highlight Pakistan’s struggle to keep policies aligned with market dynamics. More critically, they also reveal CPEC’s failure to engage with Pakistan’s existing renewable energy policy. Wind and solar projects were included in CPEC mainly due to Chinese companies capitalizing on Pakistan’s preexisting initiatives, rather than any strategic policy push.

Further evidence of this can be found in the absence of planned transmission lines for solar and wind power projects, creating a major bottleneck for renewable integration. The only transmission line built under CPEC—the HVDC ±660 kV Matiari-Lahore Transmission Line—evacuates power only from several CPEC coal power plants.

A Yellow Light for Speedier Transition

CPEC’s promised “green corridor” may not materialize, as previous heavy investment in thermal power has not only locked Pakistan into fossil fuels, but also created significant structural conditions that are unfavorable for new renewable energy projects.

By 2024, Pakistan’s total installed generation capacity reached 42,512 MW—largely thanks to CPEC’s 9,000 MW addition. Yet only 22,971 MW of this capacity was utilized. Weak demand reflects not only economic sluggishness, but also a tariff policy structure that penalizes high consumption.

Moreover, Pakistan’s reliance on imported fuel for power generation (including CPEC’s imported coal plants) has created high electricity prices that discourage grid power usage. Many industries have built their own captive power plants, exacerbating this underutilization of existing capacity.

A vicious cycle ensued. Under power purchase agreements, the government must compensate investors for idled capacity, which eventually drove up per-unit electricity price for end consumers. Higher prices further suppressed consumption, exacerbating grid underutilization. Transmission losses and inefficient bill collection added to the crisis. Unpaid obligations to power producers—known as “circular debt”—reached $8.6 billion by mid-2024, of which $1.7 billion was owed to CPEC Independent Power Producers.

Faced with expensive and unreliable grid power, households and businesses have turned to rooftop solar. This trend coincided with China’s aggressive solar module price cuts to boost exports. While many still rely on grid power at night, falling battery costs could soon enable consumers to disconnect from the grid entirely. As one former Pakistani power sector regulator put it: “It’s checkmate for the grid.”

Pakistan’s government responded to this consumer shift towards renewables by actually slowing down solar adoption to protect grid investments. In particular, it has revised net-metering policies to make distributed solar less viable for businesses and households.

Capacity to Adapt Within CPEC?

CPEC’s power sector investments have significantly expanded Pakistan’s grid capacity, but this achievement tells only half the story. While generation shortages are no longer a major concern, the country now faces an even greater challenge: entrenched inefficiencies and vested interests in the power sector. The oversupply of expensive, underutilized power plants has led to skyrocketing tariffs, which discourage consumption and fuel an exodus to rooftop solar.

Ironically, Zonergy, the Chinese company behind CPEC’s only solar farm, has now emerged as a leader in Pakistan’s distributed solar system and energy storage sector. This was not a deliberate outcome of CPEC policy, but rather an unintended consequence of its failures in traditional power investment.

Fawad Hassan Fawad, former Principal Secretary to Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, told me in 2024 that “back in 2015-2016, I said in the cabinet meeting: the power sector can take down not only the government, but also the state of Pakistan.”

The structural challenges in Pakistan’s power sector are well known. Yet it remains unclear whether Chinese policymakers carefully assessed these risks before pushing CPEC’s energy investments. If China truly seeks to establish itself as a responsible development partner, it must take stock of past experience and adapt to these trends and conditions.

Hong Zhang is an Assistant Professor at the Hamilton Lugar School of Global and International Studies, Indiana University-Bloomington. She co-edits the People’s Map of Global China and Global China Pulse journal.

Header Photo: A crane filling transportation truck with coal alongside a railway track, brought by private contractors via Pakistan Railway from Sindh to Punjab, courtesy of Haani Pasha – stock.adobe.com

Infographic: Data drawn from CPEC official portal

Sources: Bloomberg, Business Recorder, CPEC Official Portal, Columbia Center on Global Energy Policy, DAWN, Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, Ministry of Foreign Affairs People’s Republic of China, National Electric Power Regulatory Authority, Nikkei Asia, Reuters, Tribune, Yale Environment 360, Zonergy

A Publication of the Stimson Center.

A Publication of the Stimson Center.