-

ASRI’s Integrated Health and Conservation Programming in Borneo

›If you have a fever in the town of Sukadana in Indonesian Borneo, the locals might suggest you go to the ASRI clinic. It’s in a little house whose front yard is crowded with bicycles and motorbikes. In the waiting room, you examine a whiteboard that explains your payment options. ASRI accepts cash. But it looks like you can also pay with labor in the clinic’s organic garden or its reforestation site. If you own a goat, you can bring in its manure and pay with that. You can even pay with durian tree seeds!

Doctoring both humans and the environment is the raison d’etre of Alam Sehat Lestari (“healthy life everlasting” in Bahasa Indonesia, or ASRI for short), an NGO dedicated to the idea that human health is so intertwined with that of the environment that trying to fix one must include trying to fix the other. Located beside Indonesia’s Gunung Palung National Park, ASRI aims to protect the park’s irreplaceable rainforests by offering health care incentives to local people to stop illegal logging. We’re supported by our sister NGO in the United States, Health in Harmony.

For both people and the forest, the task is urgent. The island of Borneo was once famously covered by rainforest. But now only half of that canopy exists, and less than one-third will remain by 2020. Beginning in the mid-20th century, loggers, palm-oil plantation companies, and farmers logged, burned, and clear-cut their way through the island. Horrifyingly, much of this destruction has taken place in “protected” areas like national parks. The relentless loss of forest has devastated biodiversity in Borneo and severely reduced habitats for many organisms, including one of humanity’s closest relatives, the orangutan – as of 2005, there were about 55,000 left, a tenth of which live in Gunung Palung. Some experts predict the orangutan will be extinct within a few decades. Despite their protected status, Gunung Palung’s forests are continually threatened by illegal logging for valuable hardwood, poor implementation of management practices, and forest fires, many of which are started to clear land for new uses. Over 50,000 hectares of the 90,000-hectare national park’s forest cover are damaged or gone.

Contributing is the fact that Borneo’s economy is based largely on extractive industries; there simply aren’t many other job options. An ASRI survey found that in the Gunung Palung area the average cost of an emergency visit to the district or regional hospital was $460 – more than the average annual income. In fact, one-third of interviewees had faced a choice between health care and food. Financial pressures like that are what drive people to illegal logging. A four-meter board can go for R110,000, or about $10 – a little less than the average villager’s monthly income of $13. Working in a rice field, by contrast, pays about a dollar a day.

Sukadana, located so close to Gunung Palung, is a boom town for these industries. It was recently made a seat of the local regency. We watch new buildings go up every week – most of them built using illegal wood chopped straight out of the national park – and workers and money are flowing in.

As forest is converted to plantations, however, pesticides and fertilizers enter the watershed, which damage water and soil quality as well as human health. Watershed destruction from logging and land conversion leads to flooding which makes it harder to raise rice and can increase rates of flood-related diseases. Logging itself is dangerous work, and there are few or no worker protections. As well, seasonal, man-made forest fires, which this ecosystem is not adapted to and which can last for months, devastate both the natural habitat and respiratory health.

Enter ASRI: Our Sukadana clinic offers high-quality, low-cost medical care to all comers, with discounts for people living in villages that do not contribute to illegal logging (which the National Park office determines using air and ground patrols). This incentive system was devised in consultation with local leaders and is intended to take advantage of powerful social ties in this rural area. But given the complexity of the connections between poverty, health, and the environmental degradation here, ASRI also attacks these problems from other angles.

For one, patients and families can pay by eco-friendly, non-cash means – some of which actually end up providing further benefit to the patients. Many choose to do a stint of labor for ASRI in our organic garden. There they learn techniques that they can apply to their own crops. Some farmers have reported making a considerable profit selling their own organic produce with the skills they learned at ASRI, and some have sworn off traditional slash-and-burn agriculture, because as organic farmers they earn more money for less work. Others decide to work at ASRI’s reforestation site, which aims to restore several hectares of burned-over, degraded grassland to its original forested state. Patients can also bring in compost or manure; rainforest seeds and seedlings; or handmade grass mats, which are snapped up by clinic staff and volunteers.

ASRI’s other programs include Goats for Widows, in which impoverished widows receive a goat and give back its organic manure and one kid. Clinic staff teach townspeople and villagers about the links between the environment and health and include information about diseases like tuberculosis during “movie nights,” when they set up a projection screen and show educational videos. Crucially, ASRI also engages in capacity-building through its trained medical volunteers, who serve as consultants for Indonesian staff doctors who are fresh out of medical school.

On the horizon is a new eco-friendly “super-clinic” that will allow us to perform major surgery and house many more inpatients. We hope that as it goes up, people will learn ways to build with less wood, and that by offering even better health care to people living around the national park, we will gain enough leverage to slow or even stop illegal logging. For the community – everyone from the next generation of Sukadanans to the gibbons and durian trees – that would be a healthy change for all.

Jenny Blair, M.D., is a physician, writer, and long-term volunteer at ASRI, along with her husband, Roberto Cipriano, a LEED-accredited professional and architect who is helping to design ASRI’s newest clinic.

Sources: Center for International Forestry Research, Food and Agriculture Organization, Gunung Palung Orangutan Conservation Program, Mongabay.com, Rainforest Action Network, Tropics, World Rainforest Movement, World Wildlife Foundation

Video and Image Credit: “Conservation – Part 1,” courtesy of AlamSehatLestari, and “Ibu Nurdiah,” used with permission, courtesy of Roberto Cipriano. -

Tunisia’s Shot at Democracy: What Demographics and Recent History Tell Us

›January 25, 2011 // By Richard Cincotta

While events in Tunisia, beginning mid-December and leading ultimately to President Ben Ali’s departure within a month, have rocked the Arab world, they leave an open question: Will Tunisia’s “Jasmine Revolution” ultimately lead to the Arab world’s first liberal democracy? [Video Below]

-

Water Security, Nonproliferation, and Aid Shocks in the Middle East

›In a report sponsored by the Stanley Foundation and the Stimson Center, authors Brian Finlay, Johan Bergenas, and Veronica Tessler discuss the implications of what a growing population and dwindling water supply will have on the people and governments of the Middle East. In the report, titled “Beyond Boundaries in the Middle East: Leveraging Nonproliferation Assistance to Address Security/Development Needs with Resolution 1540,” the authors point out that while the Middle East has six percent of the world’s population, it has only 0.7 percent of the world’s fresh water resources. This supply is expected to be halved in the coming decades due to “rapid population growth and increased standards of living in urban areas.” To make up for this shortfall, governments are turning to nuclear-powered desalination technology, which poses risks to the nonproliferation movement and the safety and stability of the region. (Editor’s note: for more on water as a strategic resource in the Middle East, see CSIS’ latest report.)

A recent study by Richard Nielsen, Michael Findley, Zachary Davis, Tara Candland, and Daniel Nielson from Bringham Young University examines the relationship of severe decreases in foreign aid to inciting violence among rebels in recipient countries. The study, “Foreign Aid Shocks as a Cause of Violent Armed Conflict”, examines aid shocks in 139 countries from 1981-2005. The authors find that when a donor country cuts off or suddenly limits aid due to economic or political reasons, this volatility upsets the status quo and gives strength to rebel groups who play upon the government’s inability to deliver adequate resources to the population. Instead of a sudden or sharp withdrawal in aid, Nielsen et al conclude that “if donors decide to remove aid, they should do so gradually over time because sudden large decreases in aid could be deadly.” -

Mapping the “Republic of NGOs” in Haiti

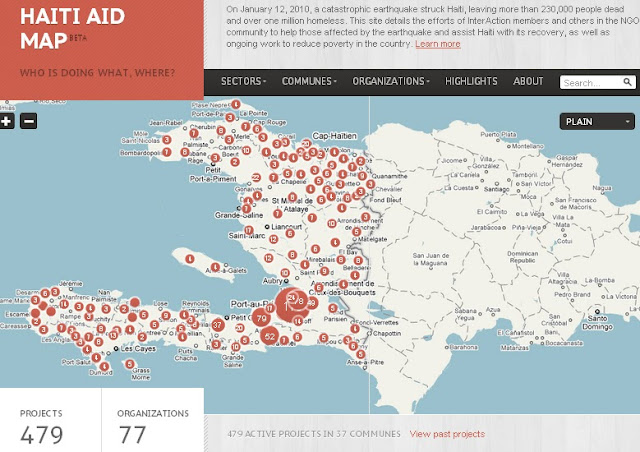

›One year after the devastating earthquake that hit Haiti, InterAction has teamed up with the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s Business Civic Leadership Center and FedEx to launch the Haiti Aid Map, an interactive visual mapping platform of individual aid projects being conducted in Haiti. The goals of the map are to increase aid transparency, facilitate partnerships, and help NGOs and others better coordinate and allocate resources to aid relief and reconstruction efforts.

With an estimated 10,000 NGOs operating on the ground – the second largest per capita in the world – Haiti has been referred to as “a republic of NGOs.” The Haiti Aid Map is an effort to help the humanitarian community – which has been criticized for lack of accountability, poor transparency, and corruption – better coordinate its response.

The map features 479 projects being operated all over the country by 77 local and international NGOs, most of which are InterAction members. Projects can be browsed by location, sector, or organization and include information on project donors, budgets, timelines, and the number of people reached by the project.

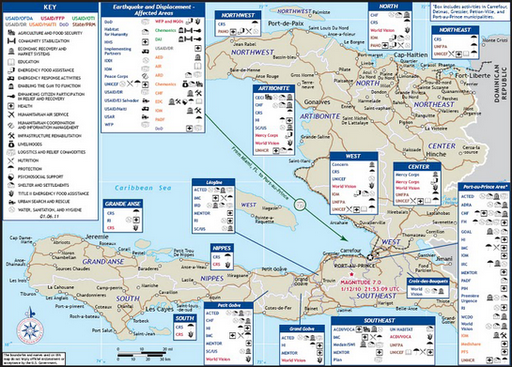

While InterAction’s map covers their donors’ response, it leaves out the thousands of government and other NGO projects being conducted in Haiti. USAID recently released a map of U.S. government projects in Haiti (see right) by sector and location.

“The goal is not to rebuild Haiti but to build a different Haiti,” said Sam Worthington, President and CEO of InterAction, speaking exactly one year after the earthquake struck at the map’s formal launch this month. “The relief effort will still be here a year from now.” The goal of the map will be to help coordinate activities as reconstruction continues in the future.

The map is the first part of a larger mapping platform, called the NGO Aid Map, which will include not only the Haiti aid map but also projects working on food security in other developing countries. The food security map is due to be launched in March 2011.

Sources: Clinton Foundation, InterAction, NPR, ReliefWeb, USIP.

Image Credit: Adapted from Haiti Aid Map. -

Linden Ellis, ChinaDialogue

China’s Biggest Environmental Stories of 2010/11

›January 21, 2011 // By Wilson Center Staff The original version of this post first appeared on ChinaDialogue’s The Daily Planet blog, December 23, 2010.

The original version of this post first appeared on ChinaDialogue’s The Daily Planet blog, December 23, 2010.

Last month I spent a few days in Washington, DC meeting mostly with people working on U.S.-China environmental relations. Among others, I met with Jennifer Turner, director of the China Environment Forum at the Wilson Center (and my former boss), and we had an exciting conversation about the biggest China environmental stories covered in the United States in 2010, and what we hope to see in 2011. I was inspired to write this post based on our conversation. This is of course neither definitive nor exhaustive, but merely my perspective on how things look from Washington.China Is Winning the Clean Energy Race. Energy was the big story in 2010. Studies show that the United States will need to renovate or retire virtually all of its power plants by 2050, and China must build a modern energy sector to serve a growing population. Both countries emphasized their intentions to build a clean energy economy in 2010 and almost immediately competition was dubbed a “race.” Soon after it was declared a two-party race, it became evident that China was winning.

China’s clean energy investment is two times greater than that of the United States, according to a Pew Charitable Trust report published last year. The news has centered upon China’s ability to make sweeping changes to domestic energy markets, in stark contrast to the United States’ inability to pass climate legislation. Most notably in 2010, China passed a regulation requiring that a percentage of all electric company profits be used for energy efficiency every year.

Energy “Co-op-etion.” Perhaps as a response to fears of “losing” the energy race, public opinion in the United States focused on new and existing energy cooperation and on market fairness. The U.S.-China Clean Energy Research Center, signed in 2009, was officially launched in 2010 and is likely to formalize a great deal of on-going cooperation on energy between the United States and China. In December, Jonathan Silver, Executive Director of the U.S. Department of Energy’s Loan Guarantee Program, spoke at a conference in San Francisco and described the developing energy relationship between China and the United States as “co-op-etition” – the two countries have complementary markets and a lot to learn from each other but will compete in U.S., Chinese, and international markets to sell clean technologies.

Concerns about the fairness of the market – initially because of changes in China’s government procurement laws discriminating against foreign clean technology companies – peaked with the U.S. Steel Workers’ petition in October. Americans are concerned that their technologies will suffer in the international market because of Chinese clean technology subsidies.

China “Ruined” Copenhagen. Perception that China ruined Copenhagen dominated the U.S. news early in the year but was softened by a more positive outlook following Cancun. Anxiety in Washington, DC regarding the accuracy of China’s CO2 data colored many debates on American participation in international climate negotiations all year.

Oil and Rare Earths. The oil spill in Dalian in July made big news in the United States as it came in the wake of the BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. Many comparisons were made, despite the enormous difference in scale between the two incidents. Rare earth elements (the spine of the clean technology industry) were another major concern that arose in 2010 in Washington. Many of America’s rare earth mines were shuttered decades ago when Chinese mines were able to produce more affordably. This year, China began restricting rare earth exports, at least partially for environmental reasons, forcing the United States to consider reopening many of its mines and how to deal domestically with the environmental effects of those mines.

In 2011 I hope that interest in China’s environment will continue in the United States, but I expect that we will see less on renewables, as stimulus money runs thin, and rising concern for more traditional pollutants and basic environmental governance in China (especially regarding water and air pollutants).

The 12th Five-Year Plan. Set to be released early 2011, the 12 Five-Year Plan will initially dominate energy stories as it outlines how China will meet its ambitious energy intensity targets. I expect nuclear energy will replace wind and solar as the big stories in 2011. Nuclear liability should be addressed in China in 2011, as it was in India in 2010. Because of the close energy business ties between China and the United States, liability laws in China are likely to be more sympathetic to the needs of American companies than India’s recent law, which exposes nuclear components suppliers to unlimited liability.

Soil Pollution Prevention and Remediation. China’s soil pollution survey was completed in 2009 and the draft Provisional Rules on Environmental Management of the Soil of Contaminated Sites was released by the Ministry of Environmental Protection for comment in December 2009. The problem is huge and significant in China’s development and construction boom, and little data has been publicly released from the survey. I expect that in 2011, we will start to see active management and enforcement, at least in major cities.

Water Quality and Quantity. Water has and will likely continue to be, the greatest environmental concern in China and abroad, given its transboundary nature. Turner suggests we will see more on control of and attention to nitrogen pollution in China’s waterways in 2011.

To chime in with your comments on what you feel were the biggest stories of 2010 and what you predict will dominate 2011, be sure to let us know below or on ChinaDialogue.

Linden Ellis is the U.S. project director of ChinaDialogue and a former project assistant for the Wilson Center’s China Environment Forum.

Sources: Asia Society, ChinaDialogue, The New York Times, Pew Charitable Trust.

Photo Credit: “Factory in Inner Mongolia,” courtesy of flickr user Bert van Dijk. -

Elizabeth Malone on Climate Change and Glacial Melt in High Asia

› “There’s nothing more iconic, I think, about the climate change issue than glaciers,” says Elizabeth Malone, senior research scientist at the Joint Global Change Research Institute and Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. Malone served as the technical lead on “Changing Glaciers and Hydrology in Asia: Addressing Vulnerability to Glacier Melt Impacts,” a USAID report released in late 2010 that explores the linkages between climate change, demographic change, and glacier melt in the Himalayas and other nearby mountain systems.

“There’s nothing more iconic, I think, about the climate change issue than glaciers,” says Elizabeth Malone, senior research scientist at the Joint Global Change Research Institute and Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. Malone served as the technical lead on “Changing Glaciers and Hydrology in Asia: Addressing Vulnerability to Glacier Melt Impacts,” a USAID report released in late 2010 that explores the linkages between climate change, demographic change, and glacier melt in the Himalayas and other nearby mountain systems.

Describing glaciers as “transboundary in the largest sense,” Malone points out that meltwater from High Asian glaciers feeds many of the region’s largest rivers, including the Indus, Ganges, Tsangpo-Brahmaputra, and Mekong. While glacial melt does not necessarily constitute a large percentage of those rivers’ downstream flow volume, concern persists that continued rapid glacial melt induced by climate change could eventually impact water availability and food security in densely populated areas of South and East Asia.

Rapid demographic change has potentially factored into accelerated glacial melt, even though the connection may not be a direct one, Malone adds.

Atmospheric pollution generated by growing populations contributes to global warming, while black carbon emissions from cooking and home heating can eventually settle on glacial ice fields, accelerating melt rates. Given such cause-and-effect relationships, Malone says that rapid population growth and the continued retreat of High Asian glaciers are “two problems that seem distant,” yet “are indeed very related.”

The “Pop Audio” series is also available as podcasts on iTunes. -

Watch: Amy Webb Girard on Integrated Development Strategies for Improved Women’s Nutrition

›“When women become pregnant…their nutrient needs shoot through the roof,” said Amy Webb Girard of Emory University’s School of Public Health in this interview with ECSP and the Global Health Initiative. Girard explains that under-nutrition is a major problem for women – especially pregnant women – in resource-poor settings.

“For example, iron requirements almost double during the course of pregnancy, but iron is one of those nutrients that are really difficult to get,” Girard explained. Meat is not readily available in many developing countries and the iron in non-meat foods is not absorbed as completely. As a result, “women by and large are unable to meet those nutrient needs,” she said.

Fortunately, there is “an arsenal of nutritional interventions available,” noted Girard, including micro-nutrient supplements, behavior change strategies, and integrated facility- and community-based delivery methods.

“Additionally I think it’s very important that we also look at food production. This is a key, key thing,” said Girard. “Women who are able to produce their own foods [and] households that can produce their own foods have greater food security.”

“A lot of these agricultural strategies serve double purposes,” Girard said. “They not only increase the available food and the quality of that food, they improve women’s livelihoods, they give them a source of income, they give them – as some studies have shown – greater ability to negotiate within their own households for how money should be spent [and] whether they should access care or not. So they actually empower women in ways beyond nutrition.” -

National Geographic’s Population Seven Billion

›The short feature above and accompanying cover article in the January 2011 issue launch National Geographic’s seven-part year-long series examining global population. The world is set to hit seven billion this year, according to current UN projections, and may reach nine billion by 2045.

The authors point out that today, 13 percent of people don’t have access to clean water globally and 38 percent lack adequate sanitation. Nearly one billion people have inadequate nutrition. Natural resources are strained. Is reducing population growth the key to addressing these problems?

Not according to Robert Kuznig, author of National Geographic’s lead article, who writes that “fixating on population numbers is not the best way to confront the future…the problem that needs solving is poverty and lack of infrastructure, not overpopulation.”

“The most aggressive population control program imaginable will not save Bangladesh from sea-level rise, Rwanda from another genocide, or all of us from our enormous environmental problems,” writes Kuznig. Speaking on NPR’s Talk of the Nation last week, he reiterated this message, saying global problems “have to be tackled whether we’re eight billion people on Earth, or seven, or nine, and the scale for them is large in any case.”

Instead, the challenge is simultaneously addressing poverty, health, and education while reducing our environmental impact, says Kuznig.

“You don’t have to impose prescriptive policies for population growth, but basically if you can help people develop a nice, comfortable lifestyle and give them the access to medical care and so on, they can do it themselves,” said Richard Harris, a science correspondent for NPR, speaking with Kuznig on Talk of the Nation.

Kuznig’s article highlights the Indian state of Kerala, where thanks to state investments in health and education, 90 percent of women in the state can read (the highest rate in India) and the fertility rate has dropped to 1.7 births per woman. One reason for this is that educated girls have children later and are more open to and aware of contraceptive options.

Whither Family Planning?

In a post on Kuznig’s piece, Andrew Revkin, of The New York Times’ Dot Earth blog, points to The New Security Beat’s recent interview with Joel E. Cohen about the crucial role of education in reducing the impact of population growth. Cohen asks: “Is it too many people or is it too few people? The truth is, both are real problems, and the fortunate thing is that we have enough information to do much better in addressing both of those problems than we are doing – we may not have silver bullets, but we’re not using the knowledge we have.”

Although the National Geographic article and video emphasize the connections between poverty reduction, health, education, and population growth, both give short shrift to family planning. It’s true that fertility is shrinking in many places, and global average fertility will likely reach replacement levels by 2030, but parts of the world – like essentially all of sub-Saharan Africa for example – still have very high rates of fertility (over five) and a high unmet demand for family planning. Globally, it is estimated that 215 million women in developing countries want to avoid pregnancy but are not using effective contraception.

Development should help reduce these levels in time, but without continued funding for reproductive health services and family planning supplies, the declining trends that Kurznig cites, which are based on some potentially problematic assumptions, are unlikely to continue.

As Kuznig told NPR, “you need birth-control methods to be available, and you need the people to have the mindset that allows them to want to use them.”

At ECSP’s “Dialogue on Managing the Planet” session yesterday at the Wilson Center, National Geographic Executive Editor Dennis Dimick urged the audience to “stay tuned – you can’t comprehensively address an issue as global and as huge as this in one article, and within this series later in the year we will talk about [family planning] very specifically.” Needless to say, I look forward to seeing it, as addressing the unmet need for family planning is a crucial part of any comprehensive effort to reduce population growth and improve environmental, social, and health outcomes.

Sources: Center for Global Development, Dot Earth, NPR, Population Reference Bureau, World Bank.

Video Credit: “7 Billion, National Geographic Magazine,” courtesy of National Geographic.

A Publication of the Stimson Center.

A Publication of the Stimson Center.