-

Climate-Induced Migration: Catastrophe or Adaptation Strategy?

›February 11, 2011 // By Kayly OberThe claims on climate change-induced migration have often been hyperbolic: “one billion people will be displaced from now until 2050”, “200 million people overtaken by…monsoon systems…droughts…sea-level rise and coastal flooding”, “500 million people are at extreme risk” from sea-level rise. However, hard data is difficult to come by or underdeveloped. The International Institute of Environment and Development (IIED) have set out to fill this gap with their newest publication, “Not Only Climate Change: Mobility, Vulnerability and Socio-Economic Transformations in Environmentally Fragile Areas of Bolivia, Senegal and Tanzania.” As the title suggests, the author, Cecilia Tacoli, traveled to Bolivia, Senegal, and Tanzania in order to see how environmental change affects migration patterns in real world case studies. What she found was a bit more nuanced than the headlines.

Case Studies: Bolivia, Senegal, and Tanzania

Despite existing predictions of doom and gloom, the report found that there has been no dramatic change in mobilization in each community, even in the face of recurring droughts. Instead, those who rely heavily on agriculture for subsistence have turned to seasonal or temporary migration. While previously considered a last resort, moving locally from rural to urban areas has become more common. The motivation for following this option, however, seems to be couched more in socio-economic concerns and only marginally exacerbated by the environment.

“All the case study locations,” writes Tacoli, “are in areas affected by long-term environmental change (desertification, soil degradation, deforestation) rather than extreme weather events. However, in the majority of locations residents identify a precipitating event – a particularly severe drought, an epidemic of livestock disease, the unintended impact of infrastructure – as the tipping point that results in drastic changes in local livelihoods. In all cases, socio-economic factors are what make these precipitating environmental events so catastrophic.”

Practical Policy Prescriptions

Although the report finds that the environment wasn’t currently the main driver of migration in Bolivia, Senegal, or Tanzania, it acknowledges that it may play a larger role in the future: “Environmental change undoubtedly increases the number of people mobile,” Tacoli told BBC News. “But catastrophe like droughts and floods tend to overlap with social and structural upheaval, like the closure of other sources of local employment that might have protected people against total dependence on the land.”

As such, Tacoli suggests treating migration as a practical adaptation strategy rather than a problem. “The concentration of population in both large and small urban centers has the potential to reduce pressure on natural resources for domestic and productive uses,” she writes.

For example, Tacoli argues that the resulting remittances and investments from migrants in urban centers fuel “a crucial engine of economic growth” in smaller towns where land prices are cheaper. This, in turn, creates further employment opportunities.

The report also encourages policymakers to focus on local interventions, such as ensuring more equitable access to land, promoting the sustainable management of natural resources to reduce vulnerability, and investing in education, access to roads, and transportation to markets. These programs would help diversify and bolster non-agricultural livelihoods, thus reducing to the risks of climate variability.

“Local non-farm activities,” writes Tacoli, “can be an important part of adaptation to climate change for the poorer groups, and the nature of the activities can contribute to a relative reduction in local environmental change.”

Avoiding Backlash

Tacoli points out that “by downplaying political and socio-economic factors in favor of an emphasis on environmental ones, alarmist predictions of climate change-induced migration can result in inappropriate policies, for example forced resettlement programmes, that will do little to protect the rights of those vulnerable to environmental change.”

However, Tacoli is careful not to over-extend her policy prescriptions. In an email to the New Security Beat she emphasized that the case studies were not intended to be representative:The emphasis is on the need to have a detailed understanding of the local context – socio-economic, cultural and political – to understand the impacts of climate change on migration and mobility…Generalizations are not usually helpful for policy-making, and a grounded understanding of the local factors that influence livelihood responses (of which mobility and migration are one aspect) is certainly a better starting point. The aim of the report is to contribute to the building of collective knowledge on these issues, rather than provide a definitive account.

Sources: BBC News, Christian Aid, Commission on Climate Change and Development, Global Humanitarian Forum, Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe.

Photo Credit: “Villager in Tanzania,” courtesy of flickr user vredeseilanden. -

Eliya Zulu on Population Growth, Family Planning, and Urbanization in Africa

› “The whole push for population control or to stabilize populations in Africa in the ’70s and the ’80s mostly came out of the West,” said Eliya Zulu of the African Institute for Development Policy (AFIDEP) in this interview with ECSP. Then new research brought to light the fact that many women in Africa actually wanted to control their fertility themselves, but they didn’t have access to family planning.

“The whole push for population control or to stabilize populations in Africa in the ’70s and the ’80s mostly came out of the West,” said Eliya Zulu of the African Institute for Development Policy (AFIDEP) in this interview with ECSP. Then new research brought to light the fact that many women in Africa actually wanted to control their fertility themselves, but they didn’t have access to family planning.

“It kind of put the African leaders who really didn’t want to talk anything about fertility control and so on in a fix,” Zulu said. “Because all of sudden now it was the African women themselves who are saying we need these services – it was not an imposition from the West.”

Based in Nairobi, Kenya, Zulu said that part of what he does at AFIDEP is “try to get African countries to think about the future.” Current economic growth in parts of Africa simply can’t match population growth, but improving access to family planning and child/maternal health infrastructure can greatly reduce fertility rates – and quickly.

“The question for Africa is: Are we going to be ready? And we need to prepare,” said Zulu. “For that to happen it’s not just about saying ‘let’s have fewer children.’ I think we also need to do this from a social developmental perspective where we also look at ways in which we can improve the quality of the population, empower women, invest in education, and so on.”

Four Factors of Success

There are several factors that are critical for successful family planning and child/maternal health efforts, said Zulu: strong political leadership, sustained commitment over time, financial investment (research has shown that over 90 percent of women in sub-Saharan Africa cannot afford contraceptives), and strong accountability mechanisms for monitoring performance of programs and use of resources.

“There are a number of countries that have shown that, even with the limited resources that Africa has, that with all the problems that Africa has, if you really emphasize those four factors that I mentioned, you can actually achieve very, very positive results,” Zulu said.

Rapid Urbanization and the Growth of Urban Poverty

Rapid urbanization is one of Africa’s biggest challenges, said Zulu. “Africa is the least urbanized region of the world now, but it’s growing at the highest rate.” If you look at historical examples from the West and Asia, “urbanization is supposed to be a good thing; urbanization has been a driver of economic development,” he said, but “the major characteristic of urbanization in Africa has been the rapid growth of urban poverty.”

“If the economies are not going to develop the capacity to absorb this population and create enough jobs for them, there’s going to be chaos, because you can’t have all these young people without having jobs for them,” said Zulu. “The challenge for many African governments is how to have sustainable urbanization and how to transform our cities into agents of development.”

The “Pop Audio” series is also available as podcasts on iTunes. -

A Dialogue on Managing the Planet

›“Collectively, the impact of humanity on the way the planet works is enormous and headed in disturbing directions,” said George Mason University professor Thomas Lovejoy in January at the first in a monthly series, “Managing the Planet,” led jointly by George Mason University and the Woodrow Wilson Center. The series will focus on how to take “environmental management to the scale of the entire planet,” as climate change, increasing energy consumption, and population growth place increasing stress on natural resources. We need to “chart a better course for the human future,” said Lovejoy.

Joining Lovejoy at the kickoff meeting were Dennis Dimick, executive environment editor at National Geographic, and Professor Molly Jahn of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. [Video Below]

Signs From Earth

“The entire human enterprise is based on the assumption of a stable climate,” said Lovejoy. The “most dramatic part of the story” in recent decades has been the melting of ice in the Arctic and in the mountain ranges of tropical zones. At current rates, tropical glaciers will completely disappear within the next 15 years. Though scientists predicted it would last until at least 2015, Bolivia’s Chacaltaya glacier – once renowned as the world’s highest elevation ski area – was reduced to a “few lumps of ice” in 2009, according to the BBC.

Glacial melt has raised water temperatures, altered species migrations, and threatened water supplies, coastal ecosystems, and the communities that depend on them, said Lovejoy. Higher ocean temperatures also cause the “fundamental partnership” between coral reefs and algae to break down, and “the Technicolor world essentially goes black and white,” he said.

Ocean acidification, fresh water shortages, melting glaciers, pollution, forest fires, and a “vast whipsaw” of temperature and weather extremes are just some of the effects human consumption has had on the planet, said Dimick. “It’s a sign from the Earth. It is telling us, ‘not all is well.’”

Finding Balance

As the world’s population nears seven billion this year, “we have one planet, yet we live like we live on four,” said Dimick. National Geographic’s new series “Population 7 Billion” seeks to answer the questions, he said, of “how do we find balance? How do we find ways to lower the intensity of our demands on an Earth that is telling us it is strained?”

Finding solutions to these challenges will require us to “look forward and confront the future,” said Dimick. “We need to rethink our whole global energy system,” he said, and “rethink our basic premise about what we need, as opposed to what we want.”

The global emissions limit of 450 parts per million (ppm) of carbon – the level needed to achieve the two-degree warming limit agreed upon at Cancun and Copenhagen – “is probably too high,” said Lovejoy. Most scientists agree that 350 ppm is a safer level; however, the world is already at “390 and climbing,” he noted, and global temperatures are projected to rise two degrees Celsius by 2035. If we want global warming to stop at two degrees, carbon emissions will need to stop growing by 2016, he said.

Figuring Out “Plan B”

“We have a problem that is presenting itself in a whole host of ways, with urgency that cannot be denied or dismissed,” said Jahn. “The way we do agriculture is a very significant contributor” to that problem, she said. Today, in the United States, “we waste 40 percent of the food we grow,” she said.

“Plan A…was about maximizing productivity at all costs,” said Jahn. “It looks like we may need another plan.” But figuring out “Plan B” will require steps by both policy and science communities. “We still have enormous gaps in our understanding towards even the basic science platform upon which these very important decisions about ways forward lie,” she said.

Managing the planet must begin with managing data so that we can “transition between data, information, and knowledge, and march this information out to…those making decisions that matter,” said Jahn. The information management structure that developed in the medical sciences and led to the creation of the National Library of Medicine is a useful model for managing the planet, she argued. “Personalized medicine” for the planet would allow people to use data to make better decisions about who should be doing what and where.

Using and expanding the knowledge base is a crucial step towards bringing together the science and policy communities on an international scale in search of solutions to managing the planet. “If we work together, we can change the world,” said Dimick.

Sources: 350 Science, BBC, Earth System Research Laboratory, United Nations Environment Program, United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

Photo Credit: “Sun Over Earth (NASA, International Space Station, 07/21/03),” courtesy of flickr user NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center. -

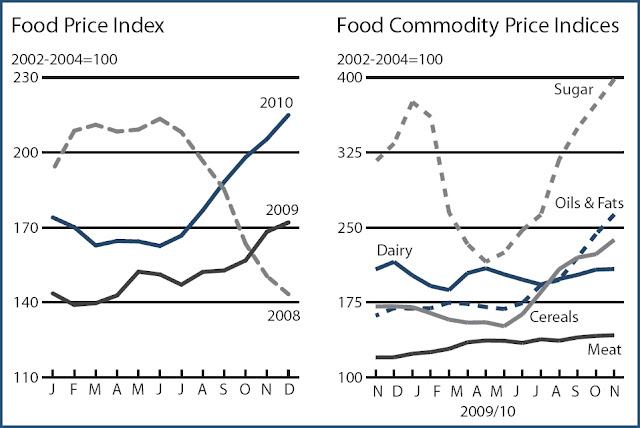

Food Price Shocks and Instability Highlight Weaknesses in Governance and Markets

›

Unrest across the Middle East has been front-page news for weeks, with commentators searching for explanations to account for the shifting political winds. Many, such as Thomas Friedman and Kevin Hall, have drawn connections between food prices and instability. But, as they point out, high food prices do not deterministically lead to unrest. Instead, rising prices highlight the degree to which governments and governance processes provide and ensure sustainable livelihoods for their people. What these and other commentators point to is that recognizing the role of government in providing food and security is vital: high food prices, they argue, don’t directly cause unrest, but high food prices in poorly managed countries creates a dangerous environment in which unrest may be more likely.

-

Portraits of Women From Afghanistan to the DRC

A Conversation on Art and Social Change

›“At the core of human rights and artistic behavior is respect for human dignity. It is this that unites art and justice,” said Jane M. Saks, executive director of the Institute for the Study of Women and Gender in the Arts and Media, speaking at an event cosponsored by the Environmental Change and Security Program and the Africa Program at the Woodrow Wilson Center. Lynsey Addario, MacArthur-winning photographer and former Institute fellow, joined Saks to share striking photographs highlighting the effects of conflict on women and girls around the world. [Video Below]

The Power of Art

“Art is inherently political because it has the power to really engage in social justice,” Saks said. The Institute that she helped found promotes art that pushes boundaries and creates conversations about peace and war, so as to “add to the accepted canon of understanding of conflict.” As part of this effort, the Institute created the exhibition, “Congo Women: Portraits of War,” composed of photographs by Addario and others about violence against women in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

Saks hopes that these “photographs saturated with human dignity” will create awareness and, ultimately, influence policy about the conflict in the DRC. The exhibition has traveled to more than 20 locations since its opening. In May 2009 it was installed at the Senate Rotunda during the Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearings on violence against women in conflict.

Addario, who said her work is drive by a desire to “give the people a voice,” has spent 15 years traveling deep into conflict zones all over the world, including Iraq, Sudan, and Afghanistan.

Women and Childbirth

Addario’s images reveal the often shocking conditions in which women around the world give birth. In Sierra Leone, she documented 18-year old Mamma Seesay, “one of thousands of women who die in childbirth.” Due to a shortage of doctors, lack of transportation, and high rates of child marriage, one in eight women in Sierra Leone die in childbirth. Afghanistan has the second highest rate of maternal mortality in the world, partly because “an Afghan woman will be pregnant up to 15 times in her life,” she said. “When you watch someone who in most other developed nations would survive without question, it’s just not fair.”

Throughout a decade of covering women in Afghanistan, Addario has sought to provide a “balanced picture” of their lives to American audiences. Her photographs show the milestones women have achieved since the fall of the Taliban: graduating college; driving cars; becoming actors, producers, or police officers; getting married; and giving birth.But her coverage of Afghanistan also contains stories like that of Fariba, an 11-year-old girl who doused herself with petrol and set herself on fire after being abused by her parents. The burn ward at the hospital in Kabul is full of such women who commit self-immolation “to escape their lives,” said Addario. An Afghan woman’s life “is worse than a donkey…there is no release for these women.”

“Give Us Your Guns”

In 2009, she went to the tribal areas of Pakistan to meet the Taliban. “Wrapped up like a cigar,” she posed as the wife of former New York Times correspondent Dexter Filkins and went into a room of 30 Taliban fighters “armed to the teeth.” The two spent the day with the Taliban and “by the end, they loved us,” she said. “The whole time they just laughed at us: ‘You Americans, you give money to the Pakistani government and they give it to us!”

While covering the conflict in Darfur, Addario had to convince UN peacekeepers to drive into a Janjaweed-occupied village so that she could verify how many people had been killed. “Every time we would go towards the village, the Janjaweed would shoot at us and so [the peacekeepers] would turn the cars around and go,” Addario said. To convince the peacekeepers to go in anyway, she said to the commander: “Just give us your guns. We’re gonna go in ourselves if you don’t.” When they finally drove towards the village, “the Janjaweed set it on fire right in front of us, and we just kept driving, and when we got there they had left,” she said.

Addario has spent years as a single woman traveling around the world and throughout conflict zones. “Women in Afghanistan think I’m insane,” she said. “They think I have a lonely, miserable life.” But she believes that as a woman working in conflict zones, she has a unique ability to access places that a man could not and a mission to tell the stories that she hears. “For me it’s about showing the greater American public what’s happening.”

Sources: Institute for the Study of Women and Gender in the Arts and Media, National Geographic, The New York Times, Public Radio International, Slate, UNICEF, and the U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations.

Photo Credit: Woman in labor with her mother on the way to the hospital in Afghanistan and a U.S. Marine in Afghanistan, used with permission courtesy of Lynsey Addario and the VII Network. -

Edward Carr, University of South Carolina

Why the Poorest Aren’t Necessarily the Most Vulnerable to Food Price Shocks

›February 8, 2011 // By Wilson Center Staff

There have been an interesting series of blog posts going around about the issue of price speculation in food markets, and the impact of that speculation on food security and people’s welfare. Going back through some of these exchanges, it seems to me that a number of folks are arguing past one another.

-

Reality Check: Challenges and Innovations in Addressing Postpartum Hemorrhage

›Heavy bleeding after childbirth, also known as postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), is one of the leading causes of maternal deaths worldwide. Globally, approximately 25 percent of all maternal deaths are caused by postpartum hemorrhage, and many mothers bleed to death due to delays in seeking health care services. On January 25th, 100 representatives from the maternal health community – a majority working directly in developing countries – convened for an all-day meeting at the Wilson Center to discuss experiences in the field and perform “reality checks” on the challenges and successes of PPH programs.

-

The International Framework for Climate-Induced Displacement

›In an article sponsored by the East-West Center, author Maxine Burkett discusses the challenges climate-induced migration presents to the people of the Pacific Islands. In the brief, titled “In Search of Refuge: Pacific Islands, Climate-Induced Migration, and the Legal Frontier,” Burkett states that millions of people in the Pacific Islands will be forced to leave their homes because of “increased intensity and frequency of storms and floods, sea-level rise, and desertification.” These low-lying islands could face a loss of agriculture and freshwater resources, or even be wiped out altogether, an outcome for which there is no international legal precedent.

In “Swimming Against the Tide: Why a Climate Displacement Treaty is Not the Answer,” published in the International Journal of Refugee Law, Jane McAdam takes a different position on the plight of so-called “climate refugees.” McAdam argues that focusing on an international treaty for these migrants distracts from efforts to establish responses for adaptation, internal migration, and migration over time. The article, writes the author, “does not deny the real impacts that climate change is already having on communities,” but rather questions the utility and political consequences of “pinning ‘solutions’ to climate change-related displacement on a multilateral instrument.”

A Publication of the Stimson Center.

A Publication of the Stimson Center.