-

Consumption and Global Growth: How Much Does Population Contribute to Carbon Emissions?

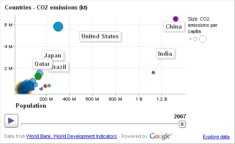

›July 6, 2011 // By Schuyler Null When discussing long-term population trends on this blog, we’ve mainly focused on demography’s interaction with social and economic development, the environment, conflict, and general state stability. In the context of climate change, population also plays a major role, but as Brian O’Neill of the National Center for Atmospheric Research put it at last year’s Society of Environmental Journalists conference, population is neither a silver bullet nor a red herring in the climate problem. Though it plays a major role, population is not the largest driver of global greenhouse gases emissions – consumption is.

When discussing long-term population trends on this blog, we’ve mainly focused on demography’s interaction with social and economic development, the environment, conflict, and general state stability. In the context of climate change, population also plays a major role, but as Brian O’Neill of the National Center for Atmospheric Research put it at last year’s Society of Environmental Journalists conference, population is neither a silver bullet nor a red herring in the climate problem. Though it plays a major role, population is not the largest driver of global greenhouse gases emissions – consumption is.

In Prosperity Without Growth, first published by the UK government’s Sustainable Development Commission and later by EarthScan as a book, economist Tim Jackson writes that it is “delusional” to rely on capitalism to transition to a “sustainable economy.” Because a capitalist economy is so reliant on consumption and constant growth, he concludes that it is not possible for it to limit greenhouse gas emissions to only 450 parts per million by 2050.

It’s worth noting that the UN has updated its population projections since Jackson’s original article. The medium variant projection for average annual population growth between now and 2050 is now about 0.75 percent (up from 0.70). The high variant projection bumps that growth rate up to 1.08 percent and the low down to 0.40 percent.

Either way, though population may play a major role in the development of certain regions, it plays a much smaller role in global CO2 emissions. In a fairly exhaustive post, Andrew Pendleton from Political Climate breaks down the math of Jackson’s most interesting conclusions and questions, including the role of population. He writes that the larger question is what will happen with consumption levels and technological advances:The argument goes like this. Growth (or decline) in emissions depend by definition on the product of three things: population growth (numbers of people), growth in income per person ($/person), and on the carbon intensity of economic activity (kgCO2/$). This last measure depends crucially on technology, and shows how far growth has been “decoupled” from carbon emissions. If population growth and economic growth are both positive, then carbon intensity must shrink at a faster rate than the other two if we are to slash emissions sufficiently.

Pendleton also brings up the prickly question of global inequity and how that impacts Jackson’s long-term assumptions:

Jackson calculates that to reach the 450 ppm stabilization target, carbon emissions would have to fall from today’s levels at an average rate of 4.9 percent a year every year to 2050. So overall, carbon intensity has to fall enough to get emissions down by that amount and offset population and income growth. Between now and 2050, population is expected to grow at an average of 0.7 percent and Jackson first considers an extrapolation of the rate of global economic growth since 1990 – 1.4 percent a year – into the future. Thus, to reach the target, carbon intensity will have to fall at an average rate of 4.9 + 0.7 + 1.4 = 7.0 percent a year every year between now and 2050. This is about 10 times the historic rate since 1990.

Pause at this stage, and take note that if there were no further economic growth, carbon intensity would still have to fall at a rate of 4.9 + 0.7 = 5.6 percent, or about eight times the rate over the last 20 years. To his credit, Jackson acknowledges this – as he puts it, decoupling is vital, with or without growth. Decoupling will require both huge innovation and investment in energy efficiency and low-carbon energy technologies. One question, to which we’ll return later, is whether and how you can get this if there is no economic growth.But Jackson doesn’t stop there. He goes on to point out that taking historical economic growth as a basis for the future means you accept a very unequal world. If we are serious about fairness, and poor countries catching up with rich countries, then the challenge is much, much bigger. In a scenario where all countries enjoy an income comparable with the European Union average by 2050 (taking into account 2.0 percent annual growth in that average between now and 2050 as well), then the numbers for the required rate of decoupling look like this: 4.9 percent a year cut in carbon emissions + 0.7 percent a year to offset population growth + 5.6 percent a year to offset economic growth = 11.2 percent per year, or about 15 times the historical rate.

To further complicate how population figures into all this, Brian O’Neill’s Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences article, “Global Demographic Trends and Future Carbon Emissions,” shows that urbanization and aging trends will have differential – and potentially offsetting – impacts on carbon emissions. Aging, particularly in industrialized countries, will reduce carbon emissions by up to 20 percent in the long term. On the other hand, urbanization, particularly in developing countries, could increase emissions by 25 percent.

What do you think? Is infinite growth possible? If so, how do you reconcile that with its effects on “spaceship Earth?” Do you rely on technology to improve efficiency? Do you call it a loss and hope the benefits of growth are worth it?

Sources: Political Climate, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Prosperity Without Growth (Jackson). -

Robert Jenkins, OpenDemocracy.net

Women, Food Security, and Peacebuilding: From Gender Essentialism To Market Fundamentalism

›July 5, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThat women’s engagement in resolving and recovering from conflict is crucial to sustainable peace has been an article of faith, and an element of international law, since the UN Security Council passed Resolution 1325 in 2000. It took a decade of missed opportunities, however, for the UN to develop a systematic action plan for redeeming the promise of 1325. The September 2010 Report of the Secretary-General on women’s participation in peacebuilding contains a concrete set of commitments for UN actors working in post-conflict settings.

-

Top 10 Posts for June 2011

›Chairman of the Joint Chief of Staff Admiral Mike Mullen joined his former staffers (see “In Search of a New Security Narrative“) on the New Security Beat top 10 list last month after speaking at the Wilson Center in the inaugural Lee Hamilton lecture. Richard Cincotta’s look at Tunisia’s demographics also remained popular, joined by several posts on climate, security, and development, including ECSP’s “Yemen Beyond the Headlines” event.

1. In Search of a New Security Narrative: The National Conversation at the Wilson Center

2. Tunisia’s Shot at Democracy: What Demographics and Recent History Tell Us

3. Connections Between Climate and Stability: Lessons From Asia and Africa

4. Admiral Mullen: “Security Means More Than Defense,” Inaugural Lee Hamilton Lecture at the Wilson Center

5. Climate Adaptation, Development, and Peacebuilding in Fragile States: Finding the Triple-Bottom Line

6. One in Three People Will Live in Sub-Saharan Africa in 2100, Says UN

7. India’s Maoists: South Asia’s “Other” Insurgency

8. Eye on Environmental Security: Where Does It Hurt? Climate Vulnerability Index, Momentum Magazine

9. Helping Hands: An Integrated Approach to Development

10. Yemen Beyond the Headlines: Losing the Battle to Balance Water Supply and Population Growth -

Quality and Quanitity: The State of the World’s Midwifery in 2011

›Each year, 350,000 women die while pregnant or giving birth, as many as two million newborns die within the first 24 hours of life, and there are 2.6 million stillbirths. Sadly, the majority of these deaths could be prevented if poor and marginalized women in developing countries had access to adequate health facilities and qualified health professionals. In fact, according to the new UNFPA report, State of the World’s Midwifery 2011: Delivering Health, Saving Lives, just doubling the current number of midwives in the 58 countries highlighted in the report could avert 21 percent of maternal, fetal, and newborn deaths.Launched last week, the report is the first of its kind, using new data from 58 low-income countries with high burdens of maternal and neonatal mortality to highlight the challenges and opportunities for developing an effective midwifery workforce.

“Developing quality midwifery services should be an essential component of all strategies aimed at improving maternal and newborn health,” write the authors of the report. Qualified midwives ensure a continuum of essential care throughout pregnancy and birth, and midwives can help facilitate referrals of mothers and newborns to hospitals or specialists when needed:Unless an additional 112,000 midwives are trained, deployed, and retained in supportive environments, 38 of 58 countries surveyed might not met their target to achieve 95 per cent coverage of births by skilled attendants by 2015, as required by Millennium Development Goal 5.

There is a total shortage of 350,000 skilled midwives globally, with some countries, like Chad and Haiti, needing a tenfold increase to match demand, according to the report. But quantity isn’t the only issue; there has also been an insufficient focus on quality of care. Additionally, most countries do not have the capacity to accurately measure the number of practicing midwives, and national policies focusing on maternal and newborn health services often do not view midwifery services as a priority.

To help overcome these challenges, the report outlines a number of “bold steps” to be taken by governments, regulatory bodies, schools, professional associations, NGOs, and donor agencies in order to maximize the impact of investments, improve mutual accountability, and strengthen the midwifery workforce and services. Of course, the needs of each country are unique, and the report ends with individual country profiles that highlight country-specific maternal and neonatal health indicators.

While this report does much to highlight the critical importance of midwives in promoting the health and survival of mothers and newborns, real impact will only come when governments, communities, civil society, and development partners work together to implement these recommendations.

Sources: UNFPA.

Video Credit: UNFPA. -

Nepal to East Africa: Population, Health, and Environment Programs Compared

›“Practice, Harvest and Exchange: Exploring and Mapping the Global, Health, Environment (PHE) Network of Practice,” by the University of Rhode Island’s Coastal Resources Institute and the USAID-supported BALANCED Project, explores the successes and challenges of their global population, health, and environment (PHE) network (with a heavy presence in East Africa). In order to increase support of the nascent PHE approach, the network seeks to shorten the “collaborative distance” between “PHE champions,” so they can develop a stronger body of evidence for the links between population, health, and the environment. In their analysis, the authors write that the network has facilitated the development of independent, information-sharing relationships between “champions.” However, they also observed shortfalls in the network, such as its limited reach into less technologically advanced yet more biodiverse regions, its bias toward BALANCED meet-up event participants, and its exclusion of those experts unlikely to be included in published works. In “Linking Population, Health, and the Environment: An Overview of Integrated Programs and a Case Study in Nepal” from the Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine, Sigrid Hahn, Natasha Anandaraja, and Leona D’Agnes provide both a broad survey of the structure and content of programs using the PHE method and an in-depth case study of a successful initiative in Nepal. Hahn et al. praise the Nepalese program for simultaneously addressing deforestation from fuel-wood harvesting, indoor air pollution from wood fires, acute respiratory infections related to smoke inhalation, as well as family planning in Nepal’s densely populated forest corridors. “The population, health, and environment approach can be an effective method for achieving sustainable development and meeting both conservation and health objectives,” the authors conclude. In particular, one benefit of cross-sectoral natural resource and development programs is the inclusion of men and adolescent boys typically overlooked by strictly family planning programs.

In “Linking Population, Health, and the Environment: An Overview of Integrated Programs and a Case Study in Nepal” from the Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine, Sigrid Hahn, Natasha Anandaraja, and Leona D’Agnes provide both a broad survey of the structure and content of programs using the PHE method and an in-depth case study of a successful initiative in Nepal. Hahn et al. praise the Nepalese program for simultaneously addressing deforestation from fuel-wood harvesting, indoor air pollution from wood fires, acute respiratory infections related to smoke inhalation, as well as family planning in Nepal’s densely populated forest corridors. “The population, health, and environment approach can be an effective method for achieving sustainable development and meeting both conservation and health objectives,” the authors conclude. In particular, one benefit of cross-sectoral natural resource and development programs is the inclusion of men and adolescent boys typically overlooked by strictly family planning programs. -

Irene Kitzantides

In FOCUS Coffee and Community: Combining Agribusiness and Health in Rwanda

›June 29, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffDownload FOCUS Issue 22: “Coffee and Community: Combining Agribusiness and Health in Rwanda,” from the Wilson Center.

Rwanda, “the land of a thousand hills,” is also the land of 10 million people, making it the most densely populated country in Africa. Rwandans depend on ever-smaller plots of land for their food and livelihoods, leading to poverty, soil infertility, and food insecurity. Could Rwanda’s burgeoning specialty coffee industry hold the key to the country’s rebirth, reconciliation, and sustainable development?

In the latest issue of ESCP’s FOCUS series, author Irene Kitzantides describes the SPREAD Project’s integration of agribusiness development with community health care and education, including family planning. She outlines the project’s successes and challenges in its efforts to simultaneously improve both the lives and livelihoods of coffee farmers and their families. -

Ecological Tourism and Development in Chi Phat, Cambodia

›Chi Phat is a single-dirt-road town nestled in the Cardamom Mountains of Southwestern Cambodia, one of the largest intact forests in Southeast Asia. The town is only accessible by two routes: a three-hour river boat trip up the Phipot River or, if the road isn’t flooded by the rainy season, an exhilarating 30-minute motorbike ride from Andoung Tuek, a blip on the one paved road that runs along Cambodia’s southwestern border. Since 2007, Wildlife Alliance has been running an ecotourism project in Chi Phat (full disclosure: I used to work for Wildlife Alliance in Washington, DC).

The project has been featured in The New York Times and since its inclusion in the Lonely Planet travel guide, has become a destination for backpackers looking to leave the beaten path. I recently visited the project after spending time in neighboring Vietnam and was struck by the contrast between the densely populated and urbanized Mekong Delta and the visibility of rural poverty in Cambodia.

“Cambodia’s contemporary poverty is largely a legacy of over twenty years of political conflict,” reads a 2006 World Bank Poverty Assessment. The Pol Pot regime’s agrarian collectivization forced millions into the countryside and as a result, even in today’s predominantly-urban world, Cambodia remains 78 percent rural. Today 93 percent of Cambodia’s poor live in rural areas, two thirds of rural people face food shortages, and maternal and reproductive health outcomes in the country lag far behind those in the cities. Chi Phat and the sparsely populated northeast have over ten or twenty times the rate of maternal deaths of Phnom Penh.

A Town Transformed

Before Wildlife Alliance began the Community-Based Ecotourism (CBET) project in Chi Phat, most villagers made a living by slash-and-burn farming, illegal logging, and poaching endangered wildlife. Wildlife Alliance Founder and CEO Suwanna Gauntlett described the ecological zone around the town as “a circle of death,” in an audio interview with New Security Beat last year.

Now, Chi Phat is a rapidly growing tourism destination offering treks and bike tours. In 2010 they brought in 1,228 tourists – not huge by any means, but over twice the number from 2009. The town now boasts a micro-credit association, a school, and a health clinic that offers maternal and reproductive health services. The village is also visited by the Kouprey Express, an environmental education-mobile that provides children and teachers with lessons, trainings, and materials on habitat and wildlife protection, pollution prevention, sustainable livelihoods, water quality, waste and sanitation, energy use, climate change, and adaptation.

One villager, Moa Sarun, described to me how he went from poacher and slash-and-burn farmer, to tour guide, and finally, chief accountant:Since I have started working with CBET, I realize that the wildlife and forest can attract a lot of tourists and bring a lot of income to villagers in Chi Phat commune. I feel very regretful for what I have done in the past as the poacher…I know clearly the aim of CBET is to alleviate the poverty of local people in Chi Phat, so I am very happy to see people in Chi Phat have jobs and better livelihoods since the project has established.

It’s hard to imagine what the town would have looked like before Wildlife Alliance arrived. The visitor center, restaurant, and “pub” (really, a concrete patio with plastic chairs and a cooler filled with beer), together make up nearly half of the town’s establishments. For two dollars a night, I stayed in a homestay and lived as the locals do on a thin mattress under mosquito netting, with a bucket of cold water by the outhouse for a shower, and a car battery if I wanted to use the fan or light (but not both). These amenities place Chi Phat above average for rural Cambodia. According to 2008 World Bank data, only 18 percent of rural areas had access to improved sanitation and only 56 percent had access to an improved water source.

Poaching Persists

Real change has certainly hit Chi Phat, but illegal activities persist, as a Wall Street Journal review of the project noted. In one Wildlife Alliance survey, 95 percent of members participating in the project made less than 80 percent of their previous income and 12 percent of people made less than 50 percent. “That, to me, is a red flag,” Director of U.S. Operations Michael Zwirn acknowledged to me. Nevertheless, he said “it is well documented that it’s the most lucrative community-based ecotourism project in Cambodia. That doesn’t mean that everyone is making money, or that they’re making enough money, but the community is clearly benefiting.”

Harold de Martimprey, Wildlife Alliance’s community-based ecotourism project manager, told me in an email interview:We monitor closely the impact of the CBET project on the diminution of poaching and deforestation. We estimate that since the beginning of the project, the illegal activities have decreased by almost 70 percent.

As Chi Phat ecotourism continues to scale up, de Martimprey expressed hope that more and more villagers would participate in the project and stop destructive livelihoods.

After four years, Chi Phat has already developed enough to operate financially on its own. Wildlife Alliance will stop funding the project later this year and transition it towards total self-sustainability. The plan is to then ramp up efforts at a neighboring project in Trapeang Ruong, due to open to the public next month.

A Land of Opportunity

So far Chi Phat lacks much of what do-gooder tourists are hoping to find when they come in search of ecotourism. There is little to no information about the work of Wildlife Alliance and how ecotourism benefits the town, or the health, education, and economic benefits the villagers have received. A little more obvious justification for ecotourism’s inflated prices might appease the average backpacker used to exploitatively lower prices elsewhere in the country. The guides, staff, and host families for the most part speak little English, which does not bode well for its tourism potential. “This is a work in progress,” said de Martimprey.

Most of my time in Chi Phat, I felt like the only foreigner to ever set foot in the town – refreshing after witnessing much of the rest of Southeast Asia’s crowded backpacker scene. As Chi Phat continues to grow, hopefully it will “bring in enough people to support the community without the adverse effects of tourism,” said Zwirn. “They don’t want it to turn into the Galapagos.” Thankfully, de Martimprey told me, “Chi Phat is far from reaching this limit and can be scaled up to much bigger operation,” without negatively impacting the environment.

Luckily, plans to build a highly destructive titanium mine near the town were recently nixed by Prime Minister Hun Sen in what was an unexpected victory over industrial interests. However, soon after, the town was again under threat – this time by a proposed banana plantation nearby.

“The Cardamom Mountains are still seen as a land of opportunity for economic land concessions for some not-so-green investors looking at buying land for different purposes, and often disregarding the interest of the local people,” said de Martimprey.

Eventually Zwirn hopes that as more tourists come to the Cardamoms, they will become “a constituency for conservation,” he said. “We need to build a worldwide awareness of the Cardamoms as a destination, and as a place worth saving.”

Sources: BBC, IFAD, Phnom Penh Post, New York Times, United Nations, Wall Street Journal, Wildlife Alliance, World Bank, World Wildlife Fund.

Photo Credit: Hannah Marqusee. -

Watch: Demographic Security 101 With Elizabeth Leahy Madsen

›June 27, 2011 // By Schuyler Null“Today we are in an era of unprecedented demographic divergence, with population trends moving simultaneously in different directions. Some countries are beginning to experience population decline, while others continue to grow rapidly,” says Elizabeth Leahy Madsen, formerly the senior research associate at Population Action International (PAI). In this primer video from ECSP, Madsen explains how global demographic trends affect economic development, national security, and foreign policy.

A Publication of the Stimson Center.

A Publication of the Stimson Center.