-

Jason Bremner, Behind the Numbers

PHE Champions Bring Their Experiences From the Field to the International Family Planning Conference in Senegal

›December 8, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Jason Bremner, appeared on the Population Reference Bureau’s Behind the Numbers blog.

This past week at the 2011 International Conference on Family Planning, four practitioners from the field traveled from remote parts of the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Madagascar, and Tanzania to Dakar, Senegal, to share their successes and challenges in reaching remote communities with an integrated package of health, livelihood, and environment services. Together they made up the panel, “Reaching the Hardly Reached: Delivering Family Planning Through Population, Health, and Environment Integration.”

The panelists came from four environmental organizations whose starting point for working in these remote places was the protection of the biodiversity and natural resources upon which all life depends. Dr. Vik Mohan, physician and medical director for Blue Ventures, talked about how he and his organization transitioned from focusing initially on the conservation of coastal marine reserves and coral reefs to now working to improve health care, including access to family planning.

Blue Ventures, in response to community and women’s needs, opened a family planning clinic, and on the opening day, 20 percent of the women of reproductive age in the community came out to request contraceptives. Today they offer a whole spectrum of short- and long-acting contraceptive methods through partnerships with Marie Stopes International, Population Services International, and various funders. Blue Ventures reported that contraceptive prevalence had risen from 8 percent when they began in 2007 to 35 percent today.

Continue reading on Behind the Numbers.

Photo used with permission courtesy of PRB. Left to right: Didier Mazongo, WWF; Vik Mohan, Blue Ventures; Baraka Kalangahe, Tanzania Coastal Management Partnership; and Jason Bremner, PRB. -

New UNEP Climate Report Says Women Face “Disproportionately High Risks”

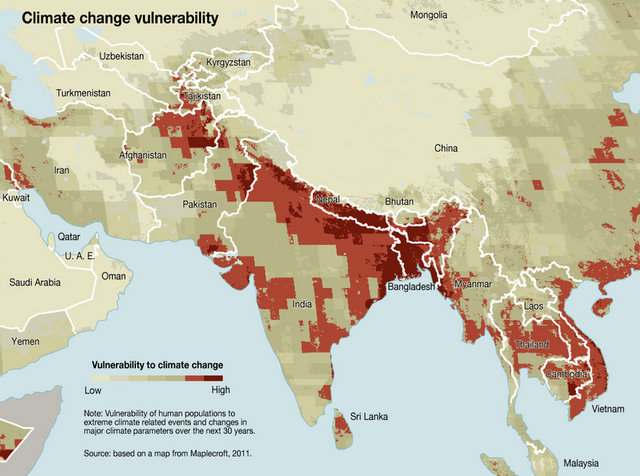

›December 8, 2011 // By Brenda ZuluA new United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) report, Women at the Frontline of Climate Change: Gender Risks and Hopes, released at COP-17, says that women, particularly those living in mountainous regions in developing countries, “face disproportionately high risks to their livelihoods and health from climate change, as well as associated risks such as human trafficking.”

Droughts, floods, and mudslides are affecting a growing number of people worldwide, in part because of climate change, but also because population growth is highest in some of the most vulnerable areas of the world. For example, in the 10 years from 1998-2008, floods affected one billion people in Asia, but only four million people in Europe.

According to UNEP, women often bear the brunt of such disasters: “In parts of Asia and Africa, where the majority of the agricultural workforce are female, the impacts of such disasters have a major impact on women’s income, food security, and health,” as they are responsible for about 65 percent of household food production in Asia and 75 percent in Africa. In addition, they are often more likely than men to lose their lives during natural disasters.

UNEP Executive Director Achim Steiner said in a press release that “women often play a stronger role than men in the management of ecosystem services and food security. Hence, sustainable adaptation must focus on gender and the role of women if it is to become successful.”

“Women’s voices, responsibilities, and knowledge on the environment and the challenges they face will need to be made a central part of governments’ adaptive responses to a rapidly changing climate,” he added.

Investing in low-carbon, resource-efficient green technologies, water harvesting, and alternatives to firewood could strengthen climate change adaptation and improve women’s livelihoods, says UNEP.

“If Insufficient, Family Planning Funds Should Be Scaled Up”

UNEP spokesperson Nick Nuttall said in an interview that there are wide differences between how people consume natural resources, with North Americans and Europeans consuming far more than someone in a developing country. We should move toward more efficient use of natural resources, make the transition to a low-carbon economy, and scale up renewable energies, which can reduce demand for fossil fuels to meet economic growth and population increases, he said.

Asked whether climate change funds should therefore support family planning, Nuttall said the UN supports the right of couples and women to choose the size of their families and that many UN agencies and NGOs provide that support already.

But, he said, “there are funds available for family planning and, if insufficient, they should be scaled up to meet the demands and requests of developing countries. Given that this is an issue far wider than climate change, these existing funding streams should be where the financial support comes, rather than from a climate fund.”

Brenda Zulu is a member of Women’s Edition for Population Reference Bureau and a freelance writer based in Zambia. Her reporting from the COP-17 meeting in Durban (see the “From Durban” series on New Security Beat) is part of a joint effort by the Aspen Institute, Population Action International, and the Wilson Center.

Sources: UNEP.

Image Credit: “Climate change vulnerability,” courtesy of Riccardo Pravettoni, UNEP/GRID-Arendal. -

Watch ‘Mother Jones’’ Kate Sheppard on Covering the Evolving Environment and Reproductive Rights Beat

› “My author bio says I cover energy, environment, and reproductive rights,” said Kate Sheppard of Mother Jones in an interview with ECSP. “One of the biggest challenges in covering that beat is even just articulating what that means.”

“My author bio says I cover energy, environment, and reproductive rights,” said Kate Sheppard of Mother Jones in an interview with ECSP. “One of the biggest challenges in covering that beat is even just articulating what that means.”

Fundamentally, Sheppard said she is interested in covering how policy decisions shape the future, which involves examining the intersections between these key issues. She spoke at a November 1 Wilson Center event on the challenges of reporting on population and environment, especially this year, when a great deal of media covered the world population reaching seven billion.

Sheppard is currently reporting on adaptation to climate change, looking at how human societies are responding to the changes that they are already experiencing, whether it be changes in migration patterns, resource availability, or food security. “I’m seeing this as a really ripe area where these things intersect, when we are talking about just how many people we are going to have in the future, and where they are going to be, and whether we can meet their needs in a society that is constantly changing,” she said.

Energy is another important area of intersection, said Sheppard. Access to energy is critical to ensuring a better future for the world’s inhabitants, but policy decisions must also take into account the fact that our fossil fuel resources are finite, she said. “We need to start thinking about ways we are going to do this sustainably for the world population in the future.” -

African Women, Most Vulnerable to Climate Change, Are Agents of Change

›December 6, 2011 // By Brenda ZuluIt is the poorest people whose lives are most undermined by changes in the weather, said Chair of the Global Leaders Council for Reproductive Health Mary Robinson at a side event on “Healthy Women, Healthy Planet” during COP-17 in Durban, South Africa. “When farmers don’t know how to predict the seasons, when there is more flooding than there was, when there are longer periods of drought and then flash flooding,” she said, people need more resilience. “They have to be even stronger in being able to cope with the drought and flooding.”From Population Action International’s Weathering Change – Fatima’s Story.

“In the past, February and March were planting months, while June and July were harvest months in the first season,” explained Constance Okollet, chairperson of the Osukura United Women Network in eastern Uganda, in an interview. “The second season started in August and September as planting months, but now we don’t have any seasons anymore.”

Okollet said that since 2007, there have been floods in her area that have destroyed homes and fields and forced some to leave their homes. “I actually had to leave when the floods destroyed my house and when I went back there was nothing; and immediately after that there was a drought after planting,” she said.

“These days we gamble with agriculture, as we are not sure when to plant. What we see now is, if it is not torrential rains, then it is a storm. During the rainy season, you find a lot of winds. We never used to see them and now we have mudslides, which are occurring every year. With heavy rains it has been difficult for people to dry cassava and groundnuts. Last month, I lost two fields of groundnuts because the rain has been very heavy,” Okollet said. “In the community, we used to harvest heavily, but it is not the same anymore.”

African women are often particularly vulnerable to such environmental disruptions. Okollet pointed out that women walk long distances to look for water and feed children before they go to school. “Women always eat little and leave the rest for their children,” she said. “Children are sick and there is a lot of death in the village because of hunger and lack of food security.”

Water-borne diseases, such as cholera, erupt after floods contaminate the water, and getting health care can be difficult for women because the health center is very far away.

Okollet said that when all this was happening, she and her fellow network members thought that maybe God was punishing them. “We only knew what was happening when Oxfam talked to us about climate change,” she said.

The Osukura United Women Network has asked the Ugandan government for help supplying early-maturing crops that will adapt to the seasonal change. The group is working to sensitize their community to the importance of hygiene and sanitation as well as working with men in the community to build wells and latrines.

“We need women to be agents of change in their local communities,” said Robinson.

Brenda Zulu is a member of Women’s Edition for Population Reference Bureau and a freelance writer based in Zambia. Her reporting from the COP-17 meeting in Durban (see the “From Durban” series on New Security Beat) is part of a joint effort by the Aspen Institute, Population Action International, and the Wilson Center.

Video Credit: “Fatima’s Story – Weathering Change Extra,” courtesy of vimeo user Population Action International. -

Gender, Family Planning Should Be Part of Climate Discussions, Says Mary Robinson

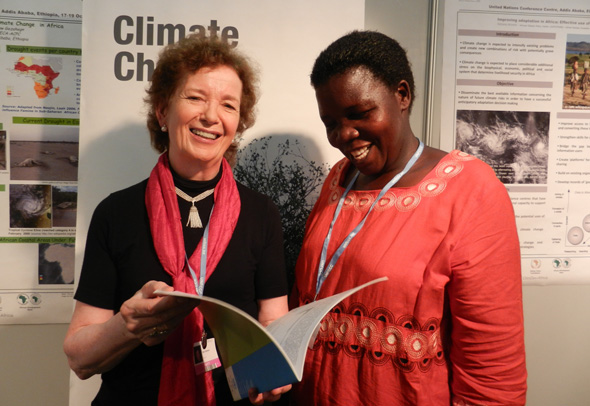

›December 6, 2011 // By Brenda ZuluSpeaking at a side event on “Healthy Women, Healthy Planet” in Durban, South Africa, Mary Robinson, chair of the Global Leaders Council for Reproductive Health, said they were seeing more female leadership at this year’s UN climate change conference (COP-17).

But Robinson, who is also chair of the Mary Robinson Foundation – Climate Justice, said there needs to be more explicit gender language in the COP-17 text to ensure that green climate funds support gender equity and money gets to women on the ground for adaptation.

“Our foundation has been helping to bring out women’s leadership at the top level in this conference to match women’s leadership at the community level,” explained Robinson, pointing out that the heads of the last three COPs are women.

Though the role of gender in climate adaptation and mitigation will likely not be prominently discussed on the floor at COP-17, Robinson said she looked forward to side conversations about a stronger focus on these issues.

Family planning, she argued, should also play a larger role. “There have been so many attempts to deflect from commitments and get into other kinds of issues that bring about some kind of stigma in this area,” said Robinson. But “those of us on the Global Leaders Council on Reproductive Health fundamentally believe in the central role played by reproductive health, access to knowledge about how to space children, and having choices about number of children.”

There are about 215 million women in the world who do not want to get pregnant but are not using modern contraception. Family planning and reproductive health services help build up a woman’s resilience to climate changes, Robinson explained.

These services are vital to improving women’s health and enable women to seek educational and work opportunities, unleashing their potential to help solve problems associated with climate change.

Brenda Zulu is a member of Women’s Edition for Population Reference Bureau and a freelance writer based in Zambia. Her reporting from the COP-17 meeting in Durban (see the “From Durban” series on New Security Beat) is part of a joint effort by the Aspen Institute, Population Action International, and the Wilson Center.

Sources: World Health Organization.

Image Credit: “Mary Robinson and Constance Okollet” at COP-17, used with permission courtesy of the Mary Robinson Foundation – Climate Justice (MRFCJ). -

Susanna Murley for The Huffington Post

Compromise Is Hard: The Problems and Promise of REDD+

›December 6, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Susanna Murley, appeared on The Huffington Post.

In Durban this week delegates from around the world are examining the options to mitigate carbon emissions. What looks like the best chance for progress? REDD+ (for Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation, plus co-benefits – like conservation, sustainable management of forests, and enhancement of forest carbon stocks). REDD+ has been seen as a potentially powerful solution to solve both poverty and deforestation – in one fell swoop.

How does it work? Essentially, these programs would be funded by developed nations to help pay for community forestry projects in developing countries, if the communities can demonstrate – with verifiable data – that their efforts are saving forests that would have been destroyed or if they are planting trees that would permanently sequester carbon.

Will this work? Many other systems have tried and failed to reduce deforestation. In Indonesia, where an area of forest about the size of Nevada has been destroyed since 1990, activists have participated in demonstrations, legal actions, blockades and destruction of property to protest timber production. Many international NGOs have joined them in their campaigns against the forestry practices in Indonesia, releasing report after report on the “State of the Forest.” The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund have attempted to regulate forestry as conditions of their loans. None of it worked, and Indonesia continues to see massive amounts of illegal logging and deforestation.

Continue reading on The Huffington Post.

Sources: Center for International Forestry Research, Gellert (2010), MongaBay.com

Photo Credit: “Oil palm plantation,” courtesy of flickr user CIFOR (Ryan Woo). -

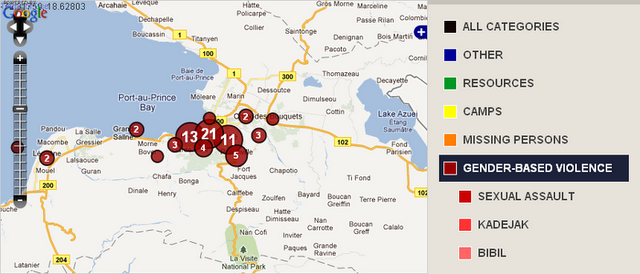

Addressing Gender-Based Violence Across Humanitarian Development in Haiti

›Women and girls living in displacement camps in post-earthquake Haiti are “the most vulnerable of a very vulnerable population,” according to Amanda Klasing, women’s rights researcher at Human Rights Watch. Klasing was joined by Leora Ward, technical advisor for women’s protection and empowerment at International Rescue Committee (IRC), and Emily Jacobi, executive director of Digital Democracy, for a November 15 panel discussion at the Wilson Center on gender-based violence in Haiti. “Unless we address the violence – the actual experience of violence that women and girls continue to experience at very high rates in Haiti – we [aren’t] going to be able to create a general environment for women and girls to participate in the rebuilding of their country,” Ward said.

-

New Population, Health, and Environment Program for Lake Victoria

›With some of Africa’s highest population densities, ethnic diversity, and biodiversity, the Great Lakes region is one of the most volatile intersections of human development and the environment. A new population, health, and environment (PHE) initiative from Pathfinder International, announced Monday at the International Conference on Family Planning in Senegal, aims to help address these issues by supporting sustainable resource management and women’s right to choose when and how often they have children.

Jointly funded by the David and Lucile Packard Foundation and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, with additional support from USAID’s Office of Population and Reproductive Health, the project will focus on Ugandan and Kenyan sections of the Lake Victoria basin.

Lake Victoria is the second largest freshwater source in the world, a biodiversity hotspot, and an important regional waterway, but regional population growth among the highest in Africa and economic development have led to declining water quality, reduced fish stocks, and industrial pollution. The basin as a whole supports upwards of 35 million people.

“This new project is a welcome development for many reasons,” said ECSP Director Geoff Dabelko. “It brings the integrated PHE approach to one of the world’s greatest lakes, it enables respected health NGO Pathfinder to pursue PHE efforts, and marks the return of a leading private donor, the MacArthur Foundation, to a group of foundations willing to support this innovative approach.”

Sono Aibe, senior advisor for strategic initiatives at Pathfinder emphasized the integrated challenges facing the region. “In these remote, resource dependent areas of the world, the interconnectedness between the health of people and the health of the environment is undeniable,” she said in a press release. “When women are empowered to participate in the sustainable management of natural resources alongside men and youth, as well as have access to sexual and reproductive health care services, their lives will improve and so will the condition of the ecosystems that they depend on.”

The project’s objective, according to Pathfinder, is to reduce threats to biodiversity, conservation, and ecosystem degradation by increasing access to family planning and sexual/reproductive health services. The project plans to develop scalable approaches that can be adopted by communities, local governments, and national governments. Technical support is to be provided by the BALANCED Project, ExpandNet, and the Population Reference Bureau.

“Lessons learned from this new project will help us better develop and design projects for vulnerable communities in fragile ecosystems, while simultaneously advocating for increased government support for integrated programs throughout the Lake Victoria Basin,” said Lucy Shillingi, Pathfinder’s country representative for Uganda.

The Lake Victoria effort will build upon the experiences of other integrated PHE efforts in the region, such as Rwanda’s SPREAD Project, Uganda’s Conservation Through Public Health, and Tanzania’s TACARE and Coastal Management Partnership.

Sources: Lake Victoria Basin Commission, Pathfinder International, UNEP.

A Publication of the Stimson Center.

A Publication of the Stimson Center.