-

The Economist

In Poor Countries, Is Lower Fertility Bad for Equality?

›August 23, 2012 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article appeared on The Economist.

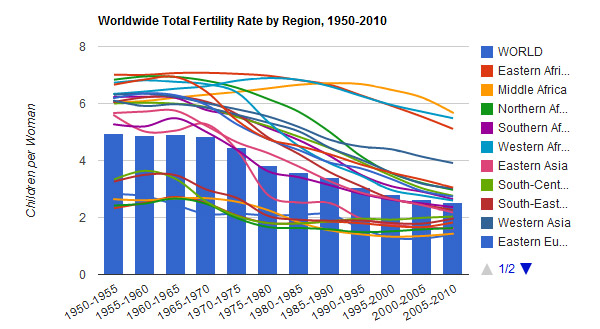

Economies benefit when people start having smaller families. As fertility falls, the share of working-age adults in the population creeps up, laying the foundation for the so-called “demographic dividend.” With fewer children, parents invest more in each child’s education, increasing human capital. People tend to save more for their retirement, so more money is available for investment. And women take paid jobs, boosting the size of the workforce. All this is good for economic growth and household income. A recent National Bureau of Economic Research study estimated that a decrease of Nigeria’s fertility rate by one child per woman would boost GDP per head by 13 percent over 20 years. But not every consequence of lower fertility is peachy. A new study by researchers at the Harvard School of Public Health identifies another and surprising effect: higher inequality in the short term.

-

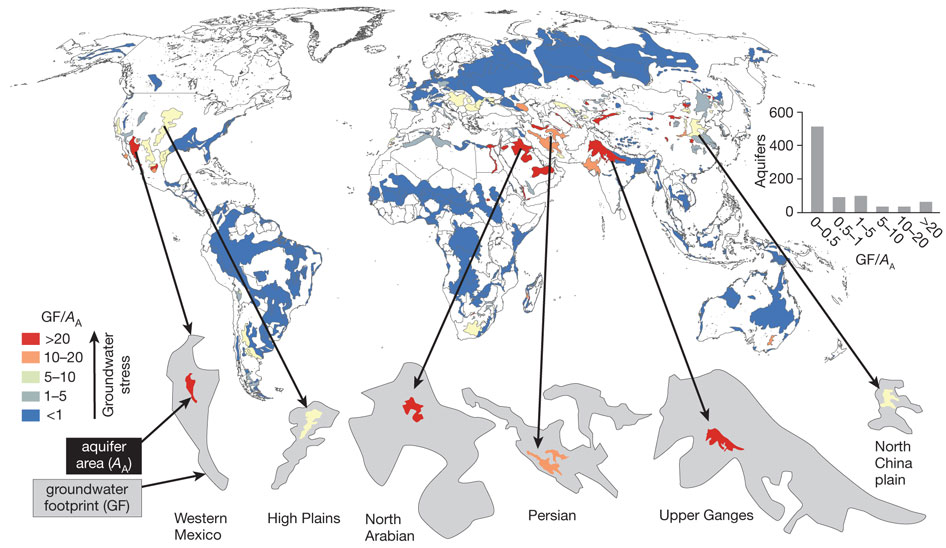

Stress Levels of Major Global Aquifers Revealed by Groundwater Footprint Study

›In the “first spatially explicit comparison of groundwater use, availability, and environmental flow for aquifers globally,” a new article in Nature finds that the “size of the global groundwater footprint is currently about 3.5 times the actual area of aquifers.” An aquifer’s footprint is the theoretical size it would need to be to sustainably support use at its current rate, so groundwater footprints being much larger than their corresponding aquifers is a sign of overuse.

-

Inside U.S. Climate Security Policy: Geoff Dabelko Interviewed by ISN

›August 20, 2012 // By Kate Diamond

Climate change “has been thought of in many quarters as something that affects folks ‘over there,’ and not as much domestically, and I think that’s a mistake,” said ECSP’s Geoff Dabelko in a recent podcast with the Zurich-based International Relations and Security Network. “I think folks are coming to a realization that there are very high economic, political, and ultimately security stakes for the United States.”

-

Taking On Domestic Violence in Post-Conflict Liberia

›Liberia is a case study in post-conflict violence against women, said panelists at the Wilson Center on July 24. “Confined merely to performing household chores and childrearing duties, from early childhood, women and girls have been socialized into subservience and powerlessness and acceptance of domestic abuse as a norm,” Annette Kiawu, deputy minister for research and technical services at the Liberian Ministry of Gender and Development, told the audience. [Video Below]

Kiawu was joined by Pamela Shifman of the Novo Foundation and Esther Karnley and Elisabeth Roesch of the International Rescue Committee (IRC). They discussed the prevalence of domestic violence in Liberia after the 14-year civil war, which ended in 2003.

Violence Stemming from Changing Norms

Kiawu pointed to women’s changing roles in Liberia as a source of household tension. She noted that women are increasingly “demanding a greater role in household decision making,” which some men see as “encroachment on their sphere of influence.”

“According to the LDHS [Liberia Demographic and Health Survey], the persistence of domestic violence is directly linked to the increased status of women on the one hand and men’s [perception] of loss of power and authority on the other,” she said. Some men’s urge to assert dominance is exacerbated by higher levels of alcohol abuse and a tendency towards violence learned during the civil war.

There has been legislation against gender-based violence – including the Rape Amendment Act, also known as the “revised rape law,” the Revised Gender-Based Violence Action Plan, and the African Union Protocol – as well as action plans and community-based groups meant to decrease the rate of domestic violence, like the Gender-Based Violence Network, an initiative designed to increase community ownership of domestic violence issues and improve response at the grassroots level. But despite these advances, Kiawu stressed that there still is a long way to go, saying that increased funding and coordination between domestic and international agencies and the Liberian government is necessary to have a real impact on the lives of the “countless women” whose lives are threatened by domestic violence.

Making Reality Match Rhetoric

Pamela Shifman agreed that domestic violence prevention programs need more funding. “So often in conflict-affected settings we hear that we need to address other issues first…that domestic violence is a back-burner issue,” she said. Domestic violence is often perceived to be “not that serious” when compared to other issues in conflict-prone and post-conflict countries.

But Shifman argued that divorcing domestic violence from other types of violence is problematic. “Violence in the home normalizes violence in the street, normalizes violence in the community, and normalizes violence by the state,” she said.

NoVo is one of the few private organizations which prioritizes domestic violence and gender equity, Shifman said, but she asserted that all humanitarian organizations should devote time and money to these issues, saying that “if we ignore domestic violence, all of the other investments we make to improve the quality of life for communities will suffer.”

Empowering women can have significant results for the whole community. Shifman remarked that “investing in women is smart economics,” citing studies which suggest directing funds towards women “pays off at huge levels” for women’s families and communities. But when women experience violence, “their potential is thwarted,” she said. “They suffer, their families suffer, their community suffers, the entire nation suffers.”

Programs targeting domestic violence need greater awareness, more long-term commitment, and more funding, she said. “We don’t expect that violence is going to end overnight – no deep-seated social problem will be solved that quickly,” she said. “In order to make a dent in improving the lives of girls and women and ending violence against girls and women, we need more direct funding” from private and public sources.

“To put it bluntly, I think the reality needs to match the rhetoric,” Shifman concluded.

Perspectives from the Field: Social Isolation

Esther Karnley described the results of interviews conducted with Liberian women, both survivors of domestic violence and fellow community members. She found that a key reason women stay in abusive relationships is financial dependence. “Most of them said, ‘it’s because we depend on the men for everything… we don’t have any money, we are not empowered financially, we depend on the men for everything. Because of that, we remain in that relationship and we get killed.’”

She added that social isolation means that many women lack the resources to leave a relationship. “We are isolated socially, we don’t have access to services, we are all by ourselves,” they told her. Without support from friends, relatives, or organizations, it can be difficult to find the means to relocate.

Part of the problem in Liberia is the prevalence of informal education, especially Sande bush schools – schools run by a traditional women’s society designed to prepare girls for marriage, teaching them traditional housekeeping methods and culminating in female circumcision. Girls leave home to attend these traditional schools for several months, which severely curtails their access to formal education. Kiawu reported that “over 60 percent of girls attending Sande school drop out of regular school.” This means that “successive generations of young children, especially young girls, are expected to forgo formal education in favor of attending the Sande school.”

In addition to formal education, Karnley said financial empowerment and legislation holding perpetrators of domestic violence accountable for their actions would enable more women to leave abusive relationships.

Reaching Both Women and Men

Each of the panelists recognized that working against domestic violence requires comprehensive societal reforms. Karnley stressed that the impetus to begin working with men came from Liberian women. “Initially when we started working on GBV issues, we talked to women, and then the women came and said, ‘OK, you talk to us every day, and when we go home, we go and meet fire. Can you also talk to our men?’” In response, the IRC developed a 16-week program designed to change men’s behavior and views about violence and relationships. Karnley also mentioned a desire to reach out to the religious community to change the constant focus on the man as the head of a relationship to one based on love.

The Liberian government is also working with churches and mosques to change norms that encourage the subjugation of women, including work with a network of religious leaders known as Christian/Muslim United against SGBV (sexual and gender based violence). Kiawu said this organization emphasizes partnership within a marriage and teaching equality to children in the home. The panelists also mentioned additional efforts to increase the responsiveness and sensitivity of the police and judicial system to domestic violence issues, as well as the need for resources like safe houses to provide relief to survivors.

“The family, far from being off limits, has to be a priority for us in the humanitarian community as we help to rebuild nations where peace not only exists between nations, and among nations, and among communities, but among families,” Shifman contended. Kiawu agreed, adding that without interventions, violence and isolation prevent women “from taking advantage of opportunities that peace presents.”

Event Resources: Photo Credit: A woman prays during a Sunday morning service in Monrovia, courtesy of Bruce Strong/Newhouse School. -

Family Planning Saves Lives, Can Help Mitigate Effects of Climate Change

›Contraceptives prevented an estimated 272,040 maternal deaths in 2008, reducing worldwide maternal mortality by 44 percent, according to a recent paper by Saifuddin Ahmed, Qingfeng Li, Li Liu, and Amy O. Tsui, published in The Lancet. But the prevention of maternal deaths could have been even higher. The study, “Maternal Deaths Averted by Contraceptive Use: An Analysis of 172 Countries,” estimates that an additional 104,000 maternal deaths – many occurring in developing parts of Africa and South Asia – could have been averted simply by satisfying existing unmet need for contraception. In sub-Saharan Africa, for example, only 22 percent of women who are married or sexually active use contraception – a far cry from the 65 percent which the study suggests is the point at which maternal deaths avoided by contraceptive use begin to plateau. Not surprisingly, this has also yielded some of the highest regional fertility rates in the world.

Such high fertility rates are driving growing concerns about scarcity and capacity in the region, and how climate change might exacerbate already-difficult development hurdles. This nexus of issues was the subject of a recent policy brief by Population Action International and the African Institute for Development Policy, titled Population, Climate Change, and Sustainable Development in Africa. The brief points out that “a large share of Africa’s population lives in areas susceptible to climate variation and extreme weather events,” and that there is an inherent tension the continent faces as it seeks to balance high population growth with climate change-induced reductions in the availability of natural resources, like water and arable land. The authors urge policymakers, rather than focusing on environment, population, and health individually, to “connect population dynamics and climate change” to address their interlinked challenges together.

-

Linking Water, Sanitation, and Biodiversity Conservation in Sub-Saharan Africa

›July 25, 2012 // By Kate DiamondWater, poverty, and the environment are “intrinsically connected,” and the development programs targeting them should be as well, writes David Bonnardeaux in Linking Biodiversity Conservation and Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene: Experiences From sub-Saharan Africa, a new Africa Biodiversity Collaborative Group briefing. In a review of 43 programs across sub-Saharan Africa, including four in-depth case studies, Bonnardeaux finds that natural synergies between water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) programming and conservation work provide opportunities for greater effectiveness in addressing both.

Integrating WASH and Conservation: A Natural Match

“WASH interventions are generally reliant on natural resources and processes, whether indirectly or directly,” he writes, and “WASH services produce outputs that are potentially detrimental to the environment if not managed properly.” At the same time, poor ecosystem management can “threaten biodiversity and jeopardize the vital services that these ecosystems in turn provide to humanity, in the form of regulation of stream flow, erosion prevention, water filtration, aquifer recharge, carbon sequestration, wildlife habitat, outdoor recreation, and flood abatement.”

Given the connections between the two, WASH and conservation efforts would benefit from programmatic integration, according to Bonnardeaux. To bring the two closer together, he recommends three tools for policymakers and development programmers: integrated river basin management and basin planning; payments for watershed services (also known as payments for environmental services); and population, health, and environment (PHE) programming.

A Whole-of-Basin Perspective

“The causal link between WASH and ecosystem health and integrity is most accentuated when

dealing with freshwater ecosystems,” writes Bonnardeaux.

In Tanzania’s Pangani River Basin, one of his in-depth case studies, a growing reliance on hydropower, urbanization, and increased agricultural demand is altering a valuable ecosystem marked by endemism and iconic landscapes, including Mount Kilimanjaro.

In response, the government and international organizations are partnering through the Pangani River Basin Management Project to developing a greater understanding of the basin’s hydrology and ecosystem, how local populations interact with that ecosystem, and how potential development scenarios could impact the basin in the future. That knowledge, paired with an intensive training program for local water officials, is enabling stronger integrated resource management, which in turn could lay the groundwork for integrating WASH and conservation interventions, writes Bonnardeaux.

Economic incentives – in this case, payments for watershed services – offer another valuable tool for building support for conservation efforts, especially when upstream communities bear a disproportionate burden of safeguarding watersheds.

In South Africa, another case study country, “increased economic development and urbanization have taken its toll on” the country’s wetlands, while unemployment and poverty have remained a persistent problem in slum areas, writes Bonnardeaux. Through the government-run Working for Wetlands program, both the environmental and socioeconomic problems of development are being targeted for improvement. The program hires “the most marginalized from society” to clear wetlands of invasive plants in order to improve its natural filtration capabilities and, in turn, improves the quality of water feeding the burgeoning urban areas.

Although Working for Wetlands, now 17 years old, has been “hugely successful,” Bonnardeaux warns that such economic incentive programs are, more often than not, extremely difficult to carry out effectively. “While there is great potential for this incentive-based conservation approach,” Bonnardeaux notes, “the reality is there are many barriers to its effective implementation.”

Building Long-Term Support for Conservation With Near-Term PHE Successes

Building support for conservation can be a difficult task. The impacts of conservation programming are “often undervalued,” Bonnardeaux writes, in part because results tend to become apparent only over the longer term. By pairing conservation efforts with nearer-term programming, like PHE efforts targeting immediate health needs, development workers can foster the kind of local support that is essential for pursuing long term goals.

The Jane Goodall Institute’s Lake Tanganyika Catchment Reforestation and Education Project (TACARE), in northwest Tanzania, offers a case in point. Established in 1994, TACARE began as a conservation program meant to protect the areas around Gombe National Park, where Goodall first began her chimpanzee research in the 1960s. Local communities, however, were more interested in better health, “with an emphasis on clear water and reduction in water-borne diseases like cholera,” writes Bonnardeaux.

By adopting local health and poverty priorities, he writes, TACARE was able to establish trust and goodwill with the communities it served, which in turn enabled it to pursue longer-term conservation goals aimed at protecting the region’s natural biodiversity.

Bonnardeaux’s work shows that regardless of how policymakers choose to combine WASH and conservation goals, well-implemented integration can yield immense benefits for practitioners, funders, and local communities.

“Linking various sectors such as WASH, forestry, agriculture, population, and community development,” he writes, “can result in cost and effort sharing which in turn can increase the effectiveness of the project including improved conservation and improved livelihoods and health.”

Sources: Bonnardeaux 2012.

Photo Credit: “Intaka Island towards Table Mountain,” courtesy of flickr user Ian Junor. -

Open Data Initiatives at USAID Reflect Move Towards Collaboration, Enabling Efforts

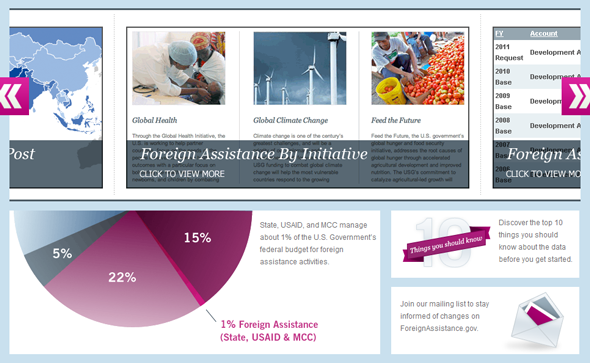

›Over the past year and a half, USAID has been busy reinventing itself. The announcement of its USAID FORWARD initiative and the release (jointly, with the State Department) of the first Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review in late 2010 signaled significant changes for the organization, including several reforms designed to modernize operations and improve transparency. Part of that effort is making data collection and dissemination more open.

Thus far, the results have been encouraging.

September of last year saw the launch of an awareness campaign focused on the Horn of Africa, co-sponsored by the Ad Council and called, somewhat confusingly, USAID FWD (famine, war, drought). As part of the program, USAID published a collection of regional maps, aggregating the organization’s substantial data pool and showing everything from food and water security to the movement of refugees and IDPs (internally displaced persons).

Using data from its own FEWS.NET site, USAID created the maps with open-source tools, allowing other organizations and concerned individuals to leverage the data for additional aid and outreach activities. Many, including the ONE Campaign and InterAction, were quick to incorporate the maps and underlying data into their own activities.

In order to promote greater data access and transparency, USAID also collaborated with the Department of State to create the Foreign Assistance Dashboard, a website that provides sortable aid budget allocation data to the general public. Launched in late 2010 with frequent updates since, the site allows users to see easily how aid is apportioned by region, sector, initiative, or other categories.

For instance, visitors can see that USAID more than quadrupled its humanitarian assistance to Pakistan in 2010 as a result of that country’s devastating flooding. Aid then fell back to near 2009 levels the following year.

Recently, USAID has also taken its open data efforts to the Web. Faced with 117,000 records of development loans provided by its own Development Credit Authority and lacking proper geographic coding, the organization undertook a pioneering experiment in crowdsourcing this June. Civilian volunteers from the online technical communities GISCorps and the Standby Task Force pitched in to help code the data, as did unaffiliated citizens attracted by social media campaigns.

The end results were outstanding: the volunteers finished the job in just 16 hours, although USAID had initially expected the operation to take 60.

Representatives from USAID recently published an illuminating case study about the crowdsourcing experiment and launched it at the Wilson Center. “By leveraging partnerships, volunteers, other federal agencies, and the private sector, the entire project was completed at no cost,” the report noted, adding that USAID hoped to have “blaze[d] a trail to help make crowdsourcing a more accessible approach for others.” One of the case study authors, Shadrock Roberts, noted that “we need to be working as hard to release relevant data we already have as we are to create it.”

USAID’s recent experiments with transparency and greater civilian participation appear to be part of a larger organizational shift toward greater openness and collaboration. Administrator Rajiv Shah seemed to confirm this in a March interview with Foreign Policy, when he spoke at length about the benefits of partnering with the private sector as well as other NGOs.

The recently reported demise, or at least great diminishing, of President Obama’s Global Health Initiative (GHI), which closed its doors amid a heated turf battle between USAID, the State Department, and PEPFAR, lends credence to this theory as well. The official GHI blog stated last week that it would “shift focus from leadership within the U.S. Government to global leadership by the U.S. Government.” This appears to indicate greater future emphasis on collaboration, with an eye toward enabling non-USAID actors to play a greater role in the development process.

It remains to be seen how USAID’s role and strategy will change over the next few years. However, results from the organization’s initial attempts at open data and open government policies have been positive in many respects, and there is reason to hope they will continue to push the boundaries in these areas.

Sources: Center for Global Development, Foreign Assistance Dashboard, Foreign Policy, Global Health Initiative, USAID.

Image Credit: Foreign Assistance Dashboard. -

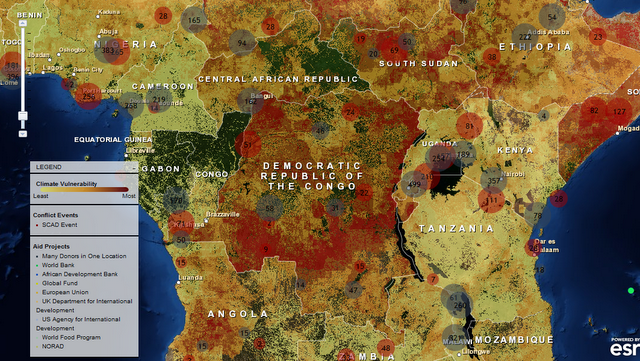

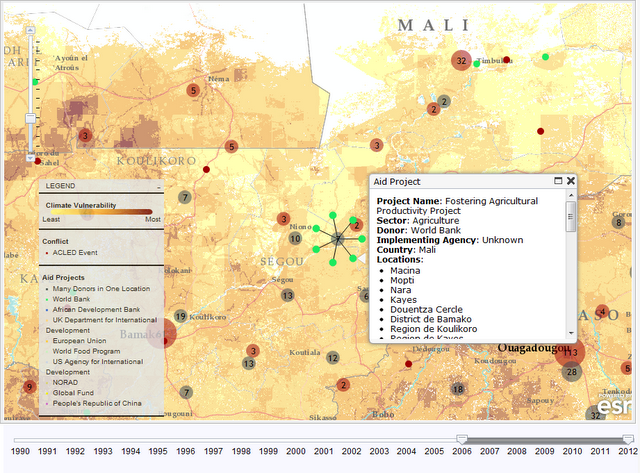

Visualizing Complex Vulnerability in Africa: The CCAPS Climate-Conflict Mapping Tool

›“Every crisis is complex, and the Sahel is no exception,” wrote USAID Assistant Administrator Nancy Lindborg in a recent Huffington Post article that called for “smarter programming and a coordivenated response” to chronic crises. “A regional drought has been overlaid with instability stemming from the coup in Mali and conflict in the northern part of that country where armed militant groups have forced the suspension of critical relief operations” and led to refugee movement into neighboring countries simultaneously challenged by drought and crop infestation. Understanding the complexity of this type of crisis, let alone visualizing the multiple factors that come into play, is a growing challenge for policymakers and analysts.

Enter version 2.0 of a mapping tool created by the Climate Change and African Political Stability Program (CCAPS) housed in the Robert S. Strauss Center for International Security and Law, based at the University of Texas, Austin.

In collaboration with the College of William and Mary, Trinity College, and the University of North Texas, and with funding by the U.S. Department of Defense’s Minerva Initiative, CCAPS originally launched the mapping tool in March of this year. The map is powered by mapping and data tools from Esri and allows users to view any combination of datasets on international development projects, national governance indicators, incidences of conflict, and climate vulnerability data.

With an intuitive interface and compelling visuals, the mapping tool is a valuable resource for policy analysts and researchers to assess the complex interactions that take place among these environmental, political, and social factors. Advanced filters allow the user to identify a subset of conflicts and aid projects and there are nine base map styles from which to choose. The mapping tool is anything but static. The team is constantly working to refine and enhance it through the inclusion of additional indicators and improvement of the interface. The updated version now includes CCAP’s new Social Conflict in Africa Database, which tracks a broad range of social and political unrest, and their partners’ real-time conflict dataset, the Armed Conflict Location and Event Dataset (ACLED), which tracks real-time conflict data. Impressively, the ACLED data will be updated weekly.

The mapping tool is anything but static. The team is constantly working to refine and enhance it through the inclusion of additional indicators and improvement of the interface. The updated version now includes CCAP’s new Social Conflict in Africa Database, which tracks a broad range of social and political unrest, and their partners’ real-time conflict dataset, the Armed Conflict Location and Event Dataset (ACLED), which tracks real-time conflict data. Impressively, the ACLED data will be updated weekly.

I asked CCAPS program manager Ashley Moran to clarify how the governance indicators work in the model. She explained:The national governance indicators are included in one of four baskets that make up the climate vulnerability model…and represent four potential sources of vulnerability: physical exposure to climate-related hazards, population density, household and community resilience, and governance and political violence. They used the term “basket” since most include several indicators that reflect the full dimensions of that source of vulnerability. The fourth basket includes five national governance indicators and one indicator of political violence.

Moran also shared plans to add more detailed national governance data to the map:We are developing a mapping tool specifically for the climate vulnerability model, which will allow users to see the component parts of the model. It will allow users to re-weight the baskets (e.g. if a user thought governance should have more weight within the model since the government response to climate hazards is key), and it will also allow users to examine an area’s vulnerability to just one or two baskets of the user’s particular interest (instead of all four baskets combined as the tool does now). When we launch this, a user will essentially be able to see the vulnerability model disaggregated into its component parts, so they’ll be able to map just the governance data in the model, if they want.

In the coming months, the CCAPS team will add more detailed historical and projected data on climate vulnerability, data on disaster response capacity, as well as international aid projects coded for climate relevance.

Each of these datasets on their own are a wealth of vital information, but understanding how they intersect and the potential impact of their interactions is crucial to improving our understanding of them individually and collectively and creating responses that are timely and long-lasting.

If you’re in the San Diego area next week, check out Ashley Moran’s presentation of the mapping tool at the Esri International User Conference and the Worldwide Human Geography Data Working Group.

Sources: The Climate Change and African Political Stability Program, The Huffington Post.

Image Credit: CCAPS

Showing posts from category Africa.