-

Nigeria Beyond the Headlines: Demography and Health [Part One]

›

“Nigeria is a country of marginalized people. Every group you talk to, from the Ijaws to the Hausas, will tell you they are marginalized,” said Peter Lewis, director of the African Studies Program at the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies. Lewis spoke at an April 25 conference on Nigeria, co-hosted by ECSP and the Wilson Center’s Africa Program, assessing the country’s opportunities for development given its demographic, governance, natural resource, health, and security challenges. [Video Below]

-

The Future of South Asian Security: Prospects for a Nontraditional Regional Architecture?

›May 7, 2012 // By Kate Diamond“The nontraditional security threats of tomorrow could themselves become sources of future traditional conflict if they’re not effectively addressed today,” said Mahin Karim, the senior associate for political and security affairs at The National Bureau of Asian Research (NBR). Karim spoke during an April 11 policy briefing on nontraditional security threats in South Asia, hosted by the Wilson Center.

“The nature of nontraditional security challenges faced by South Asia may offer opportunities to change the security agenda, perhaps even subsuming traditional security concerns in the region,” she added.

Karim, along with Roy Kamphausen, Dennis Pirages, Mallika Joseph, Amal Jayawardane, Tariq Karim, and Richard Matthew, presented findings from a three-year NBR project that assessed potential threats to the region through 2025, possible policy responses, and the feasibility of implementing those responses at the national, sub-regional, and regional levels.

In looking at the potential for environmental, population, health, resource, and demographic challenges to threaten security within the region, Karim said several trends became evident across the three workshops and five reports the project produced: the growing impact of nontraditional threats on security; the potential for the region to benefit from a demographic dividend; the growing opportunities for collaboration afforded by increasing media and technological connectivity; India’s own rise as a regional and global power; and the need to examine new and alternate options for sub-regional cooperation.

A Blurring Line Between Traditional and Nontraditional Threats

The growing importance of nontraditional threats is already apparent in India, said Mallika Joseph, the executive director for the Colombo-based Regional Centre for Strategic Studies.

“Many of the challenges which we have grown up understanding as nontraditional security challenges have now migrated and are being termed as traditional security threats, and the line dividing them continues to blur,” said Joseph.

Poor governance and resource management has exacerbated economic inequalities, which are “ever-increasing, despite sustained economic growth,” said Joseph. Meanwhile, more connectivity between different regions and classes in the country has created “greater expectations, worse disappointments, and social unrest.” That unrest has been most visible in the country’s Naxalite insurgency, where years of superficial policy “address[ing] the symptom, rather than the disease itself,” means that “what was earlier a deficit of human security has morphed itself into a situation where the state now faces a security deficit.”

As India’s policymakers attempt to minimize economic inequalities, they must do so against the backdrop of a rapidly growing population. Between now and 2025, population growth in India will account for one-fifth of growth worldwide, said Joseph. While “population trends by themselves are neither inherently good or bad, they do create conditions for peace or conflict within which states must respond.”

“Demography Is a Multiplier”

The region’s changing demographics will also impact its ability to mitigate future security threats. “Demography is a multiplier,” said Joseph. “If a state has weak governance, demography can exacerbate conditions for instability.”

Sri Lanka’s recent history is a testament to this. The country’s youth “played a very important role” in the three major insurgencies that plagued the country since the 1970s, said Amal Jayawardane, an international relations professor at the University of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Today, although the government provides free education up to the university level, youth are hampered by a disproportionately high rate of unemployment – 19 percent compared to a national average of 4.2 percent, according to the latest government labor force report. Investment in workforce opportunities for youth, along with “institutional reforms like good governance, transparency, and … eradicat[ing] corruption” will have to be considered in order to minimize the potential for youth-driven instability in the future, Jayawardane said.

Messy Boundaries, Messy Threats

“I think that one of the things that this project revealed is that we don’t have a simple definition of what constitutes South Asia per se,” said University of California, Irvine’s Richard Matthew. “It’s an interesting idea, but there’s disagreement over its actual boundaries. And it’s not clear that however we define the boundaries, they align perfectly with the threats. So the threats are messy and the boundaries of South Asia are messy.”

Many of the nontraditional threats facing the region are transnational in nature – glacial melt in the Himalayas affects water supply throughout the region, for example. Those cross-border issues merit a cross-border response.

“It isn’t like there’s a uniform response that would work for China and India and Pakistan on water security,” said Matthew. “We could and we ought to start experimenting with systems that we have reason to believe might be useful, moving them out of their national containers and into regional settings, like REDD and REDD+ and Payment for Ecosystem Services.”

Transnational Solutions for Transnational Problems

Along these lines, Mahin Karim said that the region’s youth are uniquely positioned to foster new and different ways of thinking about public policy. “The region’s youth bulge, particularly in the context of an emerging or next generation of policymakers, offers opportunities for new thinking on traditional security issues that are unhampered by the baggage of history,” she said. “Perhaps we might have a generation that’s more willing to engage multilaterally than previous or current generations have demonstrated to have been.”

Tariq Karim, Bangladesh’s high commissioner to India, said his country will depend on exactly that kind of multilateral cooperation in the coming years.

“I look at the map, I look at where Bangladesh is situated, and I can’t escape my geography,” he said. “My geography compels me to keep looking at that map and see how we can resolve our issues. On our own, it’s not possible – it’s just not possible.”

Event ResourcesSources: Sri Lanka Department of Census and Statistics.

Photo Credit: David Hawxhurst/Wilson Center. -

Jack Goldstone on Post-Cold War Trends in Armed Conflict and Challenges for the World’s Youth

›“Global trends in armed conflict have really come down since the end of the Cold War,” said George Mason University’s Jack Goldstone in this talk adapted from a presentation at the Wilson Center last fall. This drop is a reflection of decreased proxy conflicts between the Soviet Union and United States and increased interventionism from the international community. But another thing we can point to is that the world’s youth population has also declined, he said.“Global trends in armed conflict have really come down since the end of the Cold War,” said George Mason University’s Jack Goldstone in this talk adapted from a presentation at the Wilson Center last fall. This drop is a reflection of decreased proxy conflicts between the Soviet Union and United States and increased interventionism from the international community. But another thing we can point to is that the world’s youth population has also declined, he said.

“There seems to be a reasonably strong connection, between the drop-off in post-Cold War conflicts” and a decline in the proportion of youth in global population. This ageing, however, has been uneven across the globe and risks remain, said Goldstone.

“Ninety percent of all children under the age of 15 in the world today are growing up outside of North America, Europe, and the wealthy countries of East Asia,” he said, and in four or five decades time, “90 percent of the workforce of the world will be workers that have grown up outside of the rich countries.” It is this population’s “future productivity [that] will go far to determining whether quality of life gets better or worse.”

Demography and State Fragility

States across sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and the Middle East that perform poorly in indexes of state fragility also tend to have the youngest populations. “This could be just an unhappy coincidence,” said Goldstone, “but I don’t think that’s what’s going on. I think what we’re seeing is a kind of virtuous and vicious circle.”

“Where government is weak, ineffective, doesn’t provide education, doesn’t provide security, it’s advantageous both for individuals and for groups to have larger families,” he said. “However, as population grows, it’s more difficult for the government to provide adequate education and security for the larger, more youthful population.”

“On the other hand, if you can get on the track for a stronger, more legitimate government – a government that’s able to provide education, provide security of property, [and] encourage investment…fertility tends to drop quickly.” “This in turn re-enforces the ability of governments to direct resources to education and economic growth,” said Goldstone.

Critical Role of Governance

“Mobilization for political conflict draws heavily on youthful populations,” said Goldstone. As research by Henrik Urdal has shown, a bulge in the population of youth does appear to increase the risk of conflict. However, this relationship is strongly mediated by regime type. While strong democracies and autocracies are considered relatively stable, there is a “risk zone” in between, where instability is more likely.

“We live in a world where the countries with weak, fragile governments [are] about a third of the global population. But in another 30 years, if things remain as they are in terms of governance, you’re looking at closer to half the world’s population living in those more difficult circumstances,” he said.

“If the democracy is not well established, if rule of law is not well regulated, than people don’t necessary trust the outcome of peaceful electoral competition,” said Goldstone. “If people don’t like the outcome of an election, or they feel they’re being excluded, or things are one sided, they may mobilize.” This lack of political trust can result in instability and violence such as the recent protests by Thailand’s “red shirts.”

Although many Latin American and Asian states are heading towards “voluntary reduced fertility, strong economic growth, and stronger and more stable governments,” a real risk remains, he asserted. Africa, for instance, is “liable to gain a billion out of the next two billion in global population growth.”

Challenges for the Future

“For me, there are two big challenges posed by global demography,” opined Goldstone.

First, “given that 90 percent of today’s youth are in developing nations, providing them with opportunities to become productive adults through education, stable environment, [and] socialization is crucial.”

And second, in order to deliver those services, “strengthening governance in the countries where those youth live, in order for those education, security, and social services to be provided,” is absolutely necessary for economic development and reducing political instability.

While incidences of conflict have declined, the effects of those intractable conflicts that remain – in particular the sharp increase in the number of refugees and displaced populations uprooted by conflict – are solid arguments for continuing to address this risk. -

Yemen: Revisiting Demography After the Arab Spring

›April 17, 2012 // By Elizabeth Leahy Madsen

Along with other countries where the Arab Spring caught hold, Yemen has been gripped by major upheaval over the past year. Although President Ali Abdullah Saleh finally ceded power in February after his administration’s violent reprisals failed to deter protesters, the country remains at a crossroads. As its political future continues to evolve, the new government must also address a range of deep-seated economic and social challenges. In addition to claiming more than 2,000 lives, the crisis has undermined Yemenis’ livelihoods and even their access to food. A recent World Food Program survey found that more than one-fifth of Yemen’s population is living in conditions of “severe food insecurity” – double the rate measured three years ago – and another fifth is facing moderate difficulty in feeding themselves and their families.

-

Invest in Women’s Health to Improve Sub-Saharan African Food Security, Says PRB

›“Future food needs depend on our investments in women and girls, and particularly their reproductive health,” says the Population Reference Bureau’s Jason Bremner in a short video on population growth and food security (above). Understanding why, where, and how quickly populations are growing, and responding to that growth with integrated programming that addresses needs across development sectors, are crucial steps towards a food secure future, he says.

Reducing Food Insecurity by Meeting Unmet Needs

In sub-Saharan Africa, where nearly one-fourth of the population lives with some degree of food insecurity, persistently high fertility rates help drive population growth, according to the policy brief that accompanies Bremner’s video.

On average, women in the region have 5.1 children, more than twice the global average total fertility rate (TFR) of 2.5. The United Nation’s medium-variant projections (which Bremner notes are often used to predict future food need) show the region more than doubling in size by 2050, but that projection rests on the assumption that the average TFR will drop to three by mid-century.

As many as two-thirds of sub-Saharan African women want to space or limit their births, but do not use modern contraception. While the reasons for not using modern contraception are many, ranging from cultural to logistical, the lack of funding for family planning and reproductive health services remains a serious impediment to improving contraceptive prevalence and, in turn, lowering fertility rates.

“Current levels of funding for family planning and reproductive health from donors and African governments fail to meet current needs, much less the future needs,” writes Bremner.

Almost 40 percent of the region’s population is younger than 15 years old and has “yet to enter their reproductive years,” writes Bremner. “Consequently, the reproductive choices of today’s young people will greatly influence future population size and food needs in the region.”Fertility Assumptions and Population Projections in the Democratic Republic of Congo

Family Planning Is One Piece of an Integrated Puzzle

Increasing funding for family planning services would be a boon to the region, but Bremner cautions that viewing sub-Saharan Africa’s rapid population growth solely from a health perspective and in isolation from other development needs would be inherently limiting.

“Slowing population growth through voluntary family planning programs demands stronger support from a variety of development sectors, including finance, agriculture, water, and the environment,” Bremner writes. A multi-sector approach that addresses population, health, livelihood, and environment challenges could mitigate future food insecurity more effectively than single-track programming that addresses sub-Saharan Africa’s various development needs in isolation from one another.

Improving women’s role in agriculture, for example, could help minimize food insecurity on a regional scale, Bremner writes. Women make up, on average, half the agricultural labor force in sub-Saharan Africa, and yet it is more difficult for them to own arable land, obtain loans, and afford basic essentials like fertilizer that can help boost agricultural productivity. Furthermore, women’s traditional household responsibilities, like fetching water, often cut into the amount of time they are able to give to farming. With those limitations lifted, women could offer enormous capacity for meeting future food needs.

Given the complex and interconnected nature of the development challenges facing sub-Saharan Africa, integrated cross-sector programming, with an emphasis on meeting family planning needs, is essential to reducing total fertility rates while improving food security over the long-term, according to Bremner.

“Investments in women’s agriculture, education, and health are critical to improving food security in sub-Saharan Africa,” he writes.

“Improving access to family planning is a critical piece of fulfilling future food needs,” he adds, “and food security and nutrition advocates must add their voices to support investments in women and girls and voluntary family planning as essential complements to agriculture and food policy solutions.”

Sources: Population Reference Bureau.

Video Credit: Population Reference Bureau. -

Youth, Aging, and Governance: A Political Demography Workshop at the Monterey Institute of International Studies

›April 5, 2012 // By Schuyler Null“Demography is sexy – it’s about nothing but sex and death (and migration),” said Rhodes College Professor Jennifer Sciubba at the Monterey Institute of International Studies during a workshop on March 30.

Jack Goldstone of James Madison University, Richard Cincotta of the Stimson Center, and ECSP’s Geoff Dabelko joined Sciubba in a workshop for students and faculty on key developments in political demography. Sciubba and Cincotta were contributors to Goldstone’s recently released edited volume, Demography: How Population Changes Are Reshaping International Security and National Politics.

“Demography is changing the entire economic and strategic divisions of the world,” Goldstone told the room. “We’ve had a 15 year increase in life expectancy just in the last half century,” and today, “90 percent of children under 10 are growing up in developing countries.”

Many countries, said Goldstone, are caught in a difficult race between growth and governance, with governments struggling to provide services and opportunity to their growing populations. This challenge is especially acute in cities, which for the first time in human history are home to the majority of all people.

At the same time, aging is a phenomenon that will affect many developed countries. In the United Sates, the baby boomers are becoming “the grayest generation,” Goldstone said, and similar imbalances between the number of working age people and their dependent elders will soon affect Western Europe, Japan, Korea, Russia, and others.

Re-Examining the Aging Narrative

Some have predicted this “graying of the great powers” will have disastrous consequences for many of the G8, as state pension costs blunt economic growth and innovation, military adventurousness, and global influence, but Jennifer Sciubba presented a case for why fears may be overblown.

When discussing the aging phenomenon in developing countries, many analysts focus too closely on the fiscal environment, argued Sciubba. This creates tunnel vision that ignores the potential coping mechanisms that states have at their disposal. Alliances, for example, are under-accounted for, she said, and closer European Union and even NATO integration could help ameliorate the individual issues faced by aging countries like Germany, France, and Italy.

She also pointed to evidence that the developing world’s declining fertility may be have been “artificially depressed” by large proportions of women that delayed pregnancy starting in the 1990s. But now the average age of childbearing has stopped rising. The UN total fertility rate projections for industrialized states for the period 2005 to 2010 was revised upward from 1.35 children per woman in 2006 to 1.64 in 2008 and 1.71 in 2010.

This brings into focus a key leverage point for many developed countries that is not often discussed in traditional conversations about aging: making the workplace friendlier for women. Offering money to couples to have children does not work, said Sciubba – women do not make a simple monetary cost-benefit analysis when they decide to have children. Much more likely is a calculation about the cost to their professional career. Therefore, instituting more liberal leave policies and making it harder for employers to fire both men and women for taking maternity or paternity leave is more likely to have a real impact on fertility rates.

The growing efficiency – and retirement age – of today’s workers can blunt the effect of older workforces on developed economies, said Sciubba. And the stability, strong institutions, and legal protections for innovation are all advantages that will continue to attract the best and the brightest from developing countries.

The competing phenomena of aging in the developed world and continued growth in the developing – which some have dubbed the “demographic divide” – will likely make immigration a very important, possibly friction-inducing issue in the coming decades. Goldstone pointed to the challenges Europe is having today coping with immigrants from North Africa and the Middle East as a possible harbinger of things to come.

Applying Demographic Theory: The Age Structural Maturity Model

While many regions will continue to experience population growth for the next two decades, including sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and parts of East and South Asia and Latin America, the overall global trend is towards older populations. This is good news for democracy, according to Richard Cincotta.

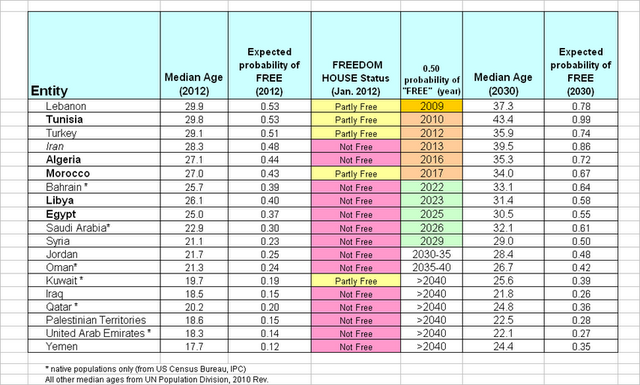

Cincotta, who consults with the National Intelligence Council on demographic issues, explained his “age structural maturity” model, which finds a historical correlation between the median age of countries and their Freedom House scores (an annual global assessments of political rights and civil liberties). Older populations tend to have more liberal regimes, while the opposite is true in younger populations. Combining this model with demographic projections, one can predict when it will become likely for democracy to emerge as a country ages. Before the Arab Spring – to some disbelief at the time – Cincotta used the model to predict that Tunisia would reach a 50/50 chance of achieving liberal democracy in 2011 (see more on this in his posts about Tunisia and the Arab Spring).

For those youthful countries that do achieve some level of liberal democracy, the model predicts they have a high likelihood of falling back towards authoritarianism (Mali is a tragic recent example).

This model, said Cincotta, can be a useful tool for analysts to challenge and add to their assessments. For example, it paints a bleak picture for democracy in Afghanistan (median age 16.6 years old), Iraq (18.5), or Yemen (17.7) and a comparatively rosier one for Tunisia (29.8), Libya (26.1), and Egypt (25.0). Some other observations may useful as well: no monarch has survived without some limits of power being introduced after countries reach a median age of 35, and military rulers too never pass that mark.

The age structural maturity model is, however, not perfect, Cincotta said. The most common outliers are autocracies (Freedom House score of “not free”) and partial democracies (“partly free”) with one-party regimes (China, North Korea), regimes led by charismatic “founder figures” (Cuba, Singapore), or those that where the regime is either supported or intimidated by a nearby autocratic state (Belarus).

Like all analyses, the model has its limitations, said Cincotta, but if used as a tool to generate “alternative hypotheses,” it can help predict dramatic political changes, like the Arab Spring. The research also suggests that the “third wave” of democratization is not over and will in fact continue to expand as countries with younger populations mature.

In conclusion, the panelists recommended the students find ways to include political demography in their work moving forward. “Consider it an alternative tool that may be useful,” said Geoff Dabelko. Policymakers today are overburdened with information and conventional analyses can sometimes become stuck in familiar lines of thought – demography can supplement these or shake them up by providing alternative narratives.

Sources: UN Population Division.

Photo Credit: Schuyler Null/Wilson Center; chart courtesy of Richard Cincotta. -

One Country, Two Stories: Marc Sommers on Rwandan Youth’s Struggle for Adulthood

›Almost an entire generation of Rwandans is confronting the prospect that they are going to be failed adults, said Marc Sommers, a fellow with Woodrow Wilson Center’s Africa Program and visiting researcher at Boston University’s African Studies Center.

-

The Middle East Program

Reflections on Women in the Arab Spring

›The Arab Spring has fascinating and powerful demographic and gender undercurrents. Last year, demographer Richard Cincotta counseled observers to pay close attention to the demonstrations: if they featured young women – as opposed to being dominated by young men and boys – it’s a sign that democracy may be on its way. To mark the occasion of International Women’s Day last week, the Wilson Center’s Middle East Program gathered observations from a cross-section of regional voices on how women have fared thus far.

Excerpted below is the entry from Moushira Khattab, former Egyptian ambassador to South Africa and the Czech and Slovak Republics, and former minister of family and population:As the global community celebrates International Women’s Day, we must hail the heroic and pivotal role Egyptian women played to make the January 25th Revolution an inspiration for the world. They joined men and took to Tahrir Square calling for freedom, dignity, and social justice. They rallied around the cause of pushing the train of political change. One year later, Egyptian women find that the train of change has not only left them behind, but has in fact turned against them. It is ironic that the revolution that empowered a country, and made every Egyptian realize the power of their voice, stopped short of women’s rights. Sadly, the only march that was kicked out of Tahrir Square was that of women celebrating 2011 International Women’s Day. Women were beaten, subjected to virginity tests, and stripped of their clothes in the very same Tahrir Square.

Download the full set of reflections from the Wilson Center’s Middle East Program.

Dormant conservative value systems are being manipulated by a religious discourse that denies women their rights. Calls for purging the sins of the old regime necessitate a reminder of the positive outcomes of laws that, although enacted under that old regime, have liberated and enhanced women’s status, including prohibiting female genital mutilation and child marriage. We also need a reminder that such gains are only a step towards these rights, and are the outcome of collective hard work along generations. Against the background of parliamentary elections, defenders of women’s rights have backed down, while young revolutionaries don’t have women’s rights on their agendas. The most telling indicator is the shameful and meager representation of women in Egypt’s post-revolution parliament. Among a handful of elected female MPs, one declared that her top priority is to repeal the law granting women the right to seek divorce.

With religious parties controlling it, the question becomes: Will this parliament be willing and able to produce a constitution that guarantees equal rights to all Egyptians regardless of gender or religion? Dare we dream that Egyptians in 2012 could have a constitution equal to that put in place by South Africans in 1996?

Showing posts from category youth.