Showing posts from category security.

-

Panetta: Diplomacy and Development Part of Wider Strategy to Achieve Security; Will They Survive Budget Environment?

›Leon Panetta – newly minted secretary of defense and former director of the CIA – gave one of his first public policy addresses yesterday at the Woodrow Wilson Center addressing national security priorities amidst a constrained budgeting environment (see video here). Under the debt ceiling agreement recently agreed to by Congress, the Pentagon is expected to achieve around $450 billion in spending cuts over the next 10 years.

Most of Secretary Panetta’s speech focused on “preserving essential capabilities,” including the ability to project power and respond to future crises, a strong military industrial base, and most importantly, a core of highly trained and experienced personnel.

But he also touched on the other two “D” s besides defense – diplomacy and development: “The reality is that it isn’t just the defense cuts; it’s the cuts on the State Department budget that will impact as well on our ability to try to be able to promote our interests in the world,” Panetta said in response to a question from ECSP Director Geoff Dabelko:National security is a word I know that we oftentimes use just when it comes to the military, and there’s no question that we carry a large part of the burden. But national security is something that is dependent on a number of factors. It’s dependent on strong diplomacy. It’s dependent on our ability to reach out and try to help other countries. It’s dependent on our ability to try to do what we can to inspire development.

Panetta’s backing of diplomacy and foreign aid as an extension of U.S. national security strategy is a continuation of vocal support by former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Mike Mullen, former Secretary of Defense Bob Gates, and others at the Pentagon, but the bigger issue remains convincing Congress, where the State Department has become a popular target for budget cutters.

If we’re dealing with Al Qaeda and dealing with the message that Al Qaeda sends, one of the effective ways to undermine that message is to be able to reach out to the Muslim world and try to be able to advance their ability to find opportunity and to be able to seek…a better quality of life. That only happens if we bring all of these tools to bear in the effort to try to promote national security.

We’ve learned the lessons of the old Soviet Union and others that if they fail to invest in their people, if they fail to promote the quality of life in their country, they – no matter how much they spend on the military, no matter how much they spend on defense, their national security will be undermined. We have to remember that lesson: that for us to maintain a strong national security in this country, we’ve got to be aware that we have to invest not only in strong defense, but we have to invest in the quality of life in this country.

Perhaps the more useful question going forward is one of priorities. Clearly there will be (and already is) less money to go around, and the Defense Department is one of the largest outlays, while State is much smaller – the military’s FY 2012 budget request was $670.9 billion; the State Department’s, $50.9 billion. So the question is: when push comes to shove, will Secretary Panetta be able to sustain his support for diplomacy and development budgets if it means larger cuts at DOD?

Sources: Government Executive, Politico, U.S. Department of Defense, U.S. Department of State.

Photo Credit: David Hawxhurst/Wilson Center. -

El Niño, Conflict, and Environmental Determinism: Assessing Climate’s Links to Instability

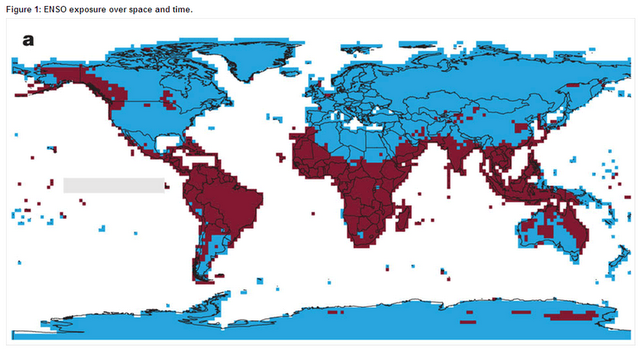

›October 5, 2011 // By Schuyler NullA recent Nature article on climate’s impact on conflict has generated controversy in the environmental security community for its bold conclusions about links between the global El Niño/La Niña cycle and the probability of intrastate conflict.

-

Digging Deeper: Water, Women, and Conflict

›

It’s not just “carrying water from a water point, but it’s discharging responsibilities that a woman has for using and managing water which may make her vulnerable to violence and bring her into risky areas,” said Dennis Warner, senior technical advisor for water and sanitation at Catholic Relief Services (CRS), at the Wilson Center on August 29. [Video Below]

-

Gates and Winnefeld: Development a Fundamental Part of National Security

› “As we’ve learned in Iraq and Afghanistan, reconstruction, development, and governance are crucial to any long-term success – it is a lesson we forget at our peril,” said Former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates in a video address commemorating the U.S. Agency for International Development’s 50th anniversary this fall. Gates was joined by Admiral James Winnefeld, Jr., the vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, in a post on USAID’s Impact blog to reinforce the importance of development and USAID in particular to U.S. national security.

“As we’ve learned in Iraq and Afghanistan, reconstruction, development, and governance are crucial to any long-term success – it is a lesson we forget at our peril,” said Former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates in a video address commemorating the U.S. Agency for International Development’s 50th anniversary this fall. Gates was joined by Admiral James Winnefeld, Jr., the vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, in a post on USAID’s Impact blog to reinforce the importance of development and USAID in particular to U.S. national security.

USAID was created on November 3, 1961 as part of a total overhaul of U.S. foreign assistance by President Kennedy. From the start, President Kennedy understood that the agency would play a role not just in development abroad but in improving U.S. security as well.

The agency is marking its 50th anniversary in an environment where development and security are seen as perhaps more linked than ever.

Winnefeld described the work that USAID and the military do as going hand-in-hand, saying that “together, we play a critical role in America’s effort to stabilize countries and build responsive local governance.”

In country after country, Winnefeld said, “USAID’s development efforts are critical to our objective of creating peace and security around the world.” He added that “instability in any corner of today’s highly interconnected world can impact everyone. Development efforts prevent conflicts from occurring by helping countries become more stable and less prone to extremism.”

“For 50 years,” Gates said, “USAID has embodied our nation’s compassion, generosity, and commitment to advance our ideals and interests around the globe. It’s a commitment demonstrated every time this agency works hand-in-hand with communities worldwide to cure a child, build a road, or train a judge.”

“By improving global stability,” Winnefeld concluded, “USAID helps keep America safe.”

Sources: USAID.

Video Credit: USaidVideo. -

Broadening Development’s Impact: From Sustainability to Governance and Security

›John Drexhage and Deborah Murphy’s UN background paper, “Sustainable Development: From Brundtland to Rio 2012,” looks at how “sustainable development” has evolved since the 1987 Brundtland Report first brought the concept to the forefront of the international community’s attention. Drexage and Murphy write that climate change has become a “de facto proxy” for sustainable development and they offer various recommendations for how policymakers and institutions can better integrate social and economic issues into a sustainable development framework. Considering that “increasing consumption, combined with population growth, mean that humanity’s demands on the planet have more than doubled over the past 45 years,” the authors conclude that “the opportunity is ripe” to bring “real systemic change” to how the world thinks about – and acts on – sustainable development.

The World Bank’s World Development Report 2011 makes an argument for “bringing security and development together to put down roots deep enough to break the cycles of fragility and conflict.” The report gives an overview of the “interconnections among security, governance, and development” and offers recommendations on how understanding and addressing them can end cycles of violence. Just as Drexhage and Murphy point to population changes as a challenge for sustainable development, the World Bank notes that growing urbanization has “increased the potential for crime, social tension, communal violence, and political instability” locally while a threefold increase in refugees and internally displaced persons over the past 30 years has put strains on regional relations around the world. Though the report acknowledges that there’s no quick fix to any of these problems, the conclusion underlining the report’s findings is that “strengthening legitimate institutions and governance to provide citizen security, justice, and jobs is crucial to break cycles of violence.” -

Loren Landau: We Need to Move Beyond Traditional Views of Migration

› Addressing the role of subnational actors, from local governments to mining companies, is increasingly critical to understanding migration, said Loren Landau, director of the African Center for Migration and Society at the University of the Witwatersrand, in an interview with ECSP. These actors frequently exert more influence than national governments over human resources because they control the “space in which people live, the space in which they produce,” Landau said.

Addressing the role of subnational actors, from local governments to mining companies, is increasingly critical to understanding migration, said Loren Landau, director of the African Center for Migration and Society at the University of the Witwatersrand, in an interview with ECSP. These actors frequently exert more influence than national governments over human resources because they control the “space in which people live, the space in which they produce,” Landau said.

Migration is most frequently seen as an aberration or a temporary coping mechanism, but this conception is outdated. According to Landau, “especially as rural livelihoods become less viable, movement will be the norm.”

Local and global actors must recognize that “people are moving, and they are moving to a whole range of new places,” he said. These new places will need attention and resources, but we will need to move beyond traditional views of migration in order to respond to the challenge. -

Edward Carr, Open the Echo Chamber

Food Security and Conflict Done Badly…

›The original version of this article, by Edward Carr, appeared on Open the Echo Chamber.

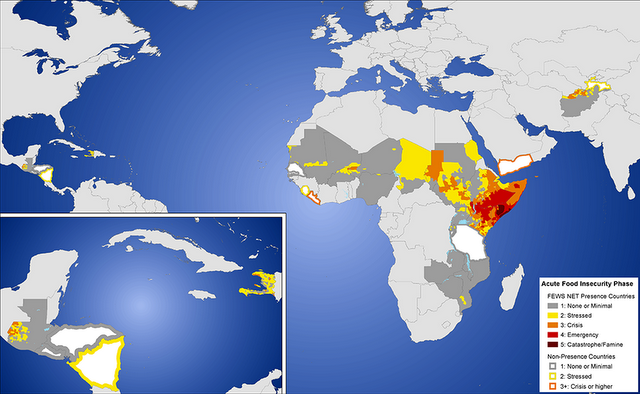

Over at the Guardian, Damian Carrington has a blog post arguing that “Food is the ultimate security need.” He bases this argument on a map produced by risk analysts Maplecroft, which sounds quite rigorous:The Maplecroft index [represented on the map], reviewed last year by the World Food Programme, uses 12 types of data to derive a measure of food risk that is based on the UN FAO’s concept. That covers the availability, access and stability of food supplies, as well as the nutritional and health status of populations.

I’m going to leave aside the question of whether we can or should be linking food security to conflict – Marc Bellemare is covering this issue in his research and has a nice short post up that you should be reading. He also has a link to a longer technical paper where he interrogates this relationship…I am still wading through it, as it involves a somewhat frightening amount of math, but if you are statistically inclined, check it out.

Instead, I would like to quickly raise some questions about this index and the map that results. First, the construction of the index itself is opaque (I assume because it is seen as a proprietary product), so I have no idea what is actually in there. Given the character of the map, though, it looks like it was constructed from national-level data. If it was, it is not particularly useful – food insecurity is not only about the amount of food, but access to that food and entitlement to get access to the food, and these are things that tend to be determined locally. You cannot aggregate entitlement at the national level and get a meaningful understanding of food insecurity – and certainly not actionable information.

Continue reading on Open the Echo Chamber.

Image Credit: “Estimated food security conditions, 3rd Quarter 2011 (August-September 2011),” courtesy of the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) and USAID. -

Development or Security: Which Comes First?

› “Let’s take an area of conflict of great concern to us: Afghanistan. One of the very concrete questions is, do you invest your development efforts predominantly in the relatively secure parts of Afghanistan, which gives you more security gains in terms of holding them, or in the relatively insecure parts, where you’re most concerned with winning against the Taliban and the battle seems most in the balance?” With that question, Richard Danzig, the chairman of the board for the Center for a New American Security (CNAS), got to the heart of the issues being debated at a recent panel on development assistance and national security.

“Let’s take an area of conflict of great concern to us: Afghanistan. One of the very concrete questions is, do you invest your development efforts predominantly in the relatively secure parts of Afghanistan, which gives you more security gains in terms of holding them, or in the relatively insecure parts, where you’re most concerned with winning against the Taliban and the battle seems most in the balance?” With that question, Richard Danzig, the chairman of the board for the Center for a New American Security (CNAS), got to the heart of the issues being debated at a recent panel on development assistance and national security.

The discussion, hosted on September 5 by the Aspen Institute in conjunction with the Brookings Blum Roundtable on Global Poverty, brought together Rajiv Shah, the administrator of the U.S. Agency for International Development; Susan Schwab, professor at the University of Maryland and former U.S. trade representative; Sylvia Mathews Burwell, president of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation’s Global Development Program; and CNAS’ Danzig. Most of the hour-long discussion was spent debating whether assistance could be successful in insecure situations (like Afghanistan), or if a place has to have some kind of stability before assistance can really take root and successfully spur development.

Short vs. Long term

Administrator Shah, not surprisingly, made the argument that development assistance is valuable in either instance. That said, he also strongly cautioned against overpromising what aid in a place like Afghanistan can accomplish, saying that “one big mistake we’ve made is to oversell what any civilian agency can do in an environment where there’s an active military campaign.” He pointed out that “it not only raises the cost of doing the work…but it also puts people at real risk.”

Danzig took a more aggressive tone, saying that “in the great majority of cases I think it is misleading and distortive to argue for development on the grounds that it will predominantly enhance security.” He argued that more often than not, security should be a prerequisite for development: “You need to distinguish cart and horse here…in most instances…the security needs to precede the development.”

Shah and Danzig, who dominated the panel, were more in sync about what development assistance can accomplish in longer-term scenarios, when security and stability are assured. Shah in particular spoke forcefully about development assistance over time, stressing that “in the long view, in the medium term, the development priorities are national security priorities.”

Enabling Success

However, Shah did warn that aid could fall short of our goals if it not carried out in a reliable way. “Stability and predictability of finance is the single thing that’s most highly correlated with good outcomes,” he said. When our aid to a country comes and goes unreliably, flowing one year and stopping abruptly the next, it’s much harder to have the kind of positive impact we want it to have, he explained.

“Through the years, where these questions have been debated back and forth, there has been one constant,” said moderator Jessica Tuchman Mathews, president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “We have always multiplied the objectives vastly beyond the resources – always.”

Video Credit: Aspen Institute.