-

P.H. Liotta, Salve Regina University

The Real Population Bomb: Megacities, Global Security, and the Map of the Future (Book Preview)

›February 8, 2012 // By Wilson Center Staff There was a time when the city was the dominant political identity. Centuries and even millennia ago, the most advanced societies in the Mediterranean, the Near East, and South America revolved around cities that were either states in themselves or were the locus of power for larger empires and kingdoms. The time of the city is coming again, though now in a considerably less benign way.

There was a time when the city was the dominant political identity. Centuries and even millennia ago, the most advanced societies in the Mediterranean, the Near East, and South America revolved around cities that were either states in themselves or were the locus of power for larger empires and kingdoms. The time of the city is coming again, though now in a considerably less benign way. From the introduction to The Real Population Bomb:

From the introduction to The Real Population Bomb:There was a time when the city was the dominant political identity. Centuries and even millennia ago, the most advanced societies in the Mediterranean, the Near East, and South America revolved around cities that were either states in themselves or were the locus of power for larger empires and kingdoms. The time of the city is coming again, though now in a considerably less benign way.

This book is about where and how geopolitics will play out in the twenty-first century. Cumulatively it represents two decades of work from authors with seemingly dissimilar backgrounds: one is a poet, novelist, and translator; the other is a security analyst and expert in disaster response and management who has worked for two presidential administrations. Both were colleagues at the U.S. Naval War College in the early 2000s.

With the rise of massive urban centers in Africa and Asia, cities that will matter most in the twenty-first century are located in less-developed, struggling states. A number of these huge megalopolises – whether Lagos or Karachi, Dhaka or Kinshasa – reside in states often unable or simply unwilling to manage the challenges that their vast and growing urban populations pose. There are no signs that their governments will prove more capable in the future. These swarming, massive urban monsters will only continue to grow and should be of great concern to the rest of the world.

We have traveled widely and conducted fieldwork in places as disparate as the Altiplano of Bolivia; Caracas, Venezuela; Guayaquil, Ecuador; the autonomous Altai Republic in deep Siberia; and the massive slums of Egypt, India, Kenya, South Africa, and Brazil. What we share from this experience is the recognition that the world has changed before our eyes. Terms such as the “developed” and “developing” world – phrases that were always dangerous and loaded with false value – no longer have the relevance they seem to have had once. Concepts such as “first world” and “third world” are stubborn relics of Cold War thinking – just as our “mental maps” are grounded in the often difficult but known past. We must change our ways of seeing the world.

Traditionally there have been two general approaches to understanding societies and states. One is the humanitarian or ecological perspective in which the focus is on society – how people live and are affected by war, pollution, and economic globalization. The other is a realist perspective in which the focus is on the economic, political, and military relations among major powers such as the European Union, the United States, China, and Russia.

What these traditional approaches underemphasize is the overlap and natural alignment between them. To understand the map of the future, we need to critically appreciate how astonishing population growth in cities – particularly fast-growing megalopolises in weak or failing states in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia – is impacting ecology and ecosystems, human security, and the national security of Western states, as well as allies and trading partners.

For both better and worse, globalization and urban population growth have changed political and economic dynamics in ways that previous conceptions of how the world works cannot do justice. In this book we examine how developments below the nation-state level – at the municipal level – affect how we must see the world of the future. While this work is anything but a travelogue, we do visit some of the most alarming locations on the earth. Often these places have been viewed in impressionistic terms, as distant locations where “others” live – with whom “we” have little interaction. But we are far more connected than we think; whether Nigeria or Pakistan, Bangladesh or Egypt, their future is also ours. The odds seem stacked against those who live there. In the dense, overgrown neighborhoods and shantytowns of Lagos, Kinshasa, Cairo, Karachi, Lahore, or Dhaka, government authorities have failed to provide infrastructure and public services. We need urgent, collective, and innovative actions to help critical megacities weather the gathering storm.

But there is hope and strength. Though time is running short, solutions are still possible. In the end, this book is about the power and resilience of the human spirit.

P. H. Liotta’s latest book is The Real Population Bomb: Megacities, Global Security, and the Map of the Future, with James F. Miskel. As a member of the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change UN’s IPCC, he shared the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize.

Photo Credit: “Urban View: the Republic of Korea’s Second Largest City,” courtesy of United Nations Photo. -

Caryle Murphy for the Middle East Program

Saudi Arabia’s Youth and the Kingdom’s Future

›Saudi Arabia is passing through a unique demographic period. …Approximately 37 percent of the Saudi population is below the age of 14. Those under age 25 account for around 51 percent of the population, and when those under 29 are included, young people amount to two-thirds of the kingdom’s population. (In the United States, those 14 years and younger are 20 percent of the population; those 29 and below make up 41 percent.)

-

Papua New Guinea Youth Conflict Study Reveals Effects of Civil War on Young Men

›Demographic security is fast becoming a central concept in discussions about the relationship between youth and violence, and, although quantitative work has been the normal mode of research in the field, recent evidence from Papua New Guinea’s autonomous region of Bougainville shows the value of understanding local-level nuance.

Policies to support youth in post-conflict situations are important for building peace, particularly given the “youth bulge” thesis that suggests that large cohorts of marginalized young people are contributing to a demographic “arc of instability” across the developing world. However, the statistical evidence showing correlations between youth bulges and an increased risk of instability has been criticized for failing to account for the agency of youth themselves. For instance, Marc Sommers points out that there is “scant information on how and why most marginalized African youth resist engagement in violence even when it would seem to provide immediate benefits.” This lack of detailed, evidence-based knowledge can frustrate efforts to develop effective youth policies, particularly in post-conflict settings, where the risk of the persistence or even return of violence, is arguably increased by the presence of youth bulges.

Bougainville’s “Crisis Generation”

Hoping to address this lack of knowledge about how and why young people engage in peace or violence in post-conflict settings, I recently spent several weeks in Bougainville. My aim was to study how young men make lives for themselves in the social circumstances that exist nine years on from a civil war that lasted more than a decade and claimed more lives than any Pacific conflict since World War II. The qualitative evidence I collected on these pathways informed analysis in an article co-authored with Jon Barnett in the Journal of Political Geography, “Localising Peace: The Young Men of Bougainville’s ‘Crisis Generation’” (subscription required).

With a 2010 median age of just 20.4 years (projected to remain less than 25 until at least 2030) and more than 60 percent of its population less than 30 years old, Papua New Guinea is among the world’s youngest states, according to UN population data. Despite a wealth of natural resources, the state faces severe challenges to providing education, jobs, and security for a young population whose growth has for many years severely outpaced the capacity of its formal institutions. Papua New Guinea, and the region of Bougainville within it, is a state where demographic strains are reasonably expected to continue to pose risks to an already fragile state.

Bougainville’s 18-to-30-year olds, known among their peers and elders as the “crisis generation,” are those with living memory of the violence but who were too young to have fought on either side. They continue to face challenges with trauma, accessing education and work, achieving social standing, and escaping from histories of violence. These sometimes impede their capacity to participate meaningfully in local society and can lead them towards sporadic acts of violence.

Understanding the Pathways to Violence

For many young men in Bougainville, achieving critical social measures of success – such as amassing the wealth required for marriage – has become nearly impossible due to high unemployment and restricted access to education. Marriage matters, since land rights in Bougainvillean societies are generally derived matrilineally, and therefore young men who are unable to marry tend to lack secure access to land.

Education is a critical institution for young men in Bougainville. Unfortunately, the formal sector that might employ young men upon completing secondary education is very small, and therefore much of the time and money spent pursuing that education is wasted. The education system itself lacks the resources to meet the needs of all those who seek secondary education. To cope with the demand, youth are asked to sit for exams in grade 8 and again in grade 10, a practice which creates high failure rates and whittles down the student cohort from several thousand at primary level to only a few hundred at the completion of secondary schooling (few of whom then receive meaningful employment). For many, this failure to obtain a return on years of school fees places significant strain on the relationships between youth and their familial and social networks.

Some adapt to these challenges by “upgrading” their poor education through distance learning or by seeking out vocational training as a way to obtain skills relevant for rural life. But some are seen as wedged between a set of unworkable options: “Many of them are existing in a vacuum,” said one civil society leader. “They see things outside but they cannot grab them and they cannot ground themselves.”

As a result, many turn to homebrew alcohol and marijuana and a select few seek social standing by adopting displays and acts of violence that imitate the personas of former rebels. Of these choices, the first attracts the stigma of “lazy,” and the second, “dangerous.” In both cases, these stigmas risk overshadowing the legitimate challenges facing young men by distilling the complexity of the world into a simple morality crisis that itself creates divides both between and within generations.

Building Policy Prescriptions

Unfortunately, the sorts of life and trauma counseling services capable of engaging these young men remain under-supported. As one youth worker claimed of the youth who have no memory of life before the war, “They don’t know how it was before the Crisis. They think things have always been this way; that this is normal.”

In a more southern district, one young man explained of his more notorious peers, “It’s these guys roaming around, mixing with ladies and drinking, they cannot reason so they use the gun, the knife – offensive weapons. And when they are sober they regret. These people spoil the peace process here in Bougainville.”

Providing viable alternatives to these lifestyles is crucial and can only be achieved by asking young men themselves about their world, about the challenges they face, and about the strategies they take to maneuver through them. By understanding the social, cultural, and geographical specifics of a local context, this form of analysis provides a valuable starting point for determining and evaluating policy interventions that statistics alone cannot provide.

In Bougainville’s case, an expansion of vocational training and the provision of trauma counseling, regardless of whether a person was a combatant or not, are two desperately needed interventions that have the potential to increase the capacity of young men to achieve success through peaceful means.

Sources: Conciliation Resources, The Sydney Morning Herald, UN Population Division.

Photo Credit: “Mekamui/Panguna” and crossing from Buka to Bougainville, courtesy of flickr user madlemurs. -

Paul Francis, Deirdre LaPin, and Paula Rossiasco for the Africa Program

Securing Development and Peace in the Niger Delta: A Social and Conflict Analysis for Change

›Excerpted below is the introduction by Steve McDonald. The full report is available for download from the Wilson Center’s Africa Program.

This study, Securing Development and Peace in the Niger Delta: A Social and Conflict Analysis for Change, draws together a vast range of information about Nigeria’s delta region not previously available in a single publication. It richly illuminates the social history and underlying causes of unrest in the area. Equally important, the study adds to the empirical research available to us about conflict prevention and approaches to post-conflict reconstruction in regions harmed by the extraction of natural resources.

It examines the complex interactions between the social, political, economic, environmental, and security factors that drive and sustain conflict. It also reviews the main policy responses and initiatives that have already been brought to bear in the delta and maps out key policy options for the future.

Encouragingly, the study finds that many of the elements of sustainable pathways to development and peace already exist or can readily be realized. What is needed is a systematic framework and, most critically, a leadership consensus and the political will to marshal them. Nigeria’s development partners are already showing a renewed commitment to support solutions to the delta’s challenges. Imaginative dialogue and partnership between them and with critical stakeholders in government, the private sector, civil society, and communities holds the promise of yielding effective strategies for sustainable development and peace that befit the region’s unique character and history.

This study, then, emerges at a time of particular opportunity and hope. And yet it must be noted that the present time also holds a considerable potential risk. Without appropriate and thoughtful action, the legitimate aspirations of the citizens of the delta and their compatriots in Nigeria as a whole will, yet again, go unrewarded. For the Niger Delta today, any plan or project must be rooted in practical and active understanding of the origins and risks of conflict in order to sustain the momentum of peaceful development and avoid planning that does not take into account the dynamics of conflict and its core causes.

Finally, the importance of the issues dealt with in this study extends beyond the delta or Nigeria as a nation. They are much broader when viewed from Nigeria’s place in the sub-region and the world economy. While the delta is unique, there are also lessons that can be learned for other conflict situations, and especially for the expanding number of new oil producing countries along the Guinea coast. For all, the key lesson is that peace is hard work. It requires a leadership committed to equitable government, dialogue with citizens, and sustainable development.

Download the full report from the Wilson Center. -

Is Foreign Aid Worth the Cost?

›“Is foreign aid worth the cost? That’s not really the question unless you’re Ron Paul,” quipped Carol J. Lancaster, dean of the School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University, at the Wilson Center on January 23. “The real questions are: What do we want to accomplish with our foreign aid? Where should it go? And in what form?” [Video Below]

Lancaster noted that following World War II, foreign aid became “a two-pronged instrument – one as an instrument of the Cold War and the other as an extension of American values.” It has been a very “intense marriage” between the two, he said, “with one side up and the other side down at different times, as any marriage tends to be.” Truman convinced Congress to provide aid to Greece and Turkey in 1948 to combat communism, and he was able to gain approval for the Marshall Plan by “scaring the wits out of Congress” about the communist threat.

Aid Under Fire

Congressman Donald Payne (N.J.), who is the ranking Democrat on the House Foreign Affairs Committee’s Subcommittee on Africa, agreed that the Cold War was the principal reason for our foreign aid programs after World War II, as we provided hundreds of billions of dollars in aid to our supporters around the world. But, “It’s different today,” he added. “Since the end of the Cold War, more funds are going for humanitarian and development assistance, but it is still directly linked to our national interests. One in five American jobs are tied to U.S. trade, and the growth of our trading partners is our growth as well.”

Payne cautioned that there is “a new group in the House of Representatives who think we should step out of the world. They’ve told their constituents they are going to cut the budget, and foreign aid is an easy target.” Payne noted that polls show the American people think one-quarter or more of the federal budget goes to foreign aid when it is little more than one percent.

Nevertheless, there has been bipartisan support for former President Bush’s HIV/AIDS initiative in Africa which is showing remarkable results in reducing deaths from the disease. Payne added that aid to Africa is showing results in the number of economies that are doing well despite the global economic downturn.

Payne expressed frustration with the inability to enact a foreign aid authorization bill in the last several Congresses because the measures became weighted down with all manner of policy riders that were both partisan and controversial. Consequently, our foreign relations operations are solely dependent on the annual appropriations bills which tend to become encumbered as well with troublesome riders.

The Dangers of “Nation Building”

Charles O. Flickner, Jr., a 28-year Republican staff member on the Senate Budget Committee and then the Foreign Operations Appropriations Subcommittee in the House, presented a more skeptical view, saying foreign aid is not worth the $35 billion it is costing us each year, even though some of the programs have been successful and should be continued. The biggest problem in recent years, he said, has been the amount of money wasted on projects in Iraq and Afghanistan without adequate planning or execution. Money was being virtually shoveled out the door in amounts the host countries did not have the capacity to absorb, said Flickner, and as a consequence we have witnessed a lot of failed projects and corruption.

Smaller projects, which the U.S. government and private aid donors are better at, have a greater chance for success because they do not overwhelm the capacities of host countries. He cited some of the scholarships and technical training programs available for foreign nationals as being among the most worthwhile in building internal leadership capacity for the future in developing countries.

Rajiv Chandrasekaran agreed on the amount of wasted aid dollars being spent in Iraq and Afghanistan, which he has covered as a foreign correspondent for The Washington Post. He told the story of a small, dirt-poor town in Afghanistan he visited in where the bazaar was bustling with new shops and goods, and people were freely spending money on modern electronics, motor bikes, and clothes. The town was the beneficiary of a massive U.S. aid program that provided seed money for farmers to grow crops and created day labor jobs for the residents of the area. A contractor was authorized to spend $30 million on the economic development of the town during the U.S. counterinsurgency surge and that came to roughly $300 per person. It was clear to the USAID official on the ground and to the reporter that the experiment would not be sustainable over the long-term, even though there was a temporary sense of economic activity and prosperity.

Future Vulnerabilities

The panel seemed to agree that it was unfair to blame USAID for these failures since they were thrown into situations overnight they were not prepared to manage in countries that were not capable of absorbing the assistance being directed at them – all in the midst of ongoing conflict. The real test of whether the new directions being charted by the Obama Administration will work will be on the smaller, more manageable projects in which the host countries have a greater role in shaping and implementing.

Lancaster listed four vulnerabilities in the future course of U.S. foreign aid that should be avoided, including trying to merge our various interests through the State and Defense Departments with our aid programs in countries like Pakistan, where the institutions are weak and corrupt; the danger of creating an entitlement dependency through funding of HIV/AIDS drugs, where we will be guilty of causing deaths if we reduce funding; the danger of attempting to undertake too many initiatives at once, such as food aid, global health, climate change, and science and technology innovations, while simultaneously trying to reform the infrastructure of USAID; and trying too hard to demonstrate results from aid given the difficulty of disentangling causes and effects and gauging success over too short a time frame.

Event Resources:

Don Wolfensberger is director of the Congress Project at the Wilson Center. -

‘New Security Beat’ Is Five Years Old

›January 26, 2012 // By Wilson Center Staff

ECSP’s Sean Peoples, Meaghan Parker, and Schuyler Null accepted the Population Institute’s Global Media Award for Best Online Commentary at a January 12 ceremony in New York City. Five years ago, in January 2007, we launched New Security Beat. Since then we’ve established a strong editorial focus on a key but neglected niche: where population, environment, and security meet.

-

Move Beyond “Water Wars” to Fulfill Water’s Peacebuilding Potential, Says NCSE Panel

›January 26, 2012 // By Schuyler NullOne of the best talks of last week’s NCSE Environment and Security Conference was thewater security plenary on Friday. Moderator Aaron Salzberg, who is the special coordinator for water resources at the Department of State, led with a provocative question: how many in attendance think there will be war over water in the future?

-

UNEP Maps Conflict, Migration, Environmental Vulnerability in the Sahel

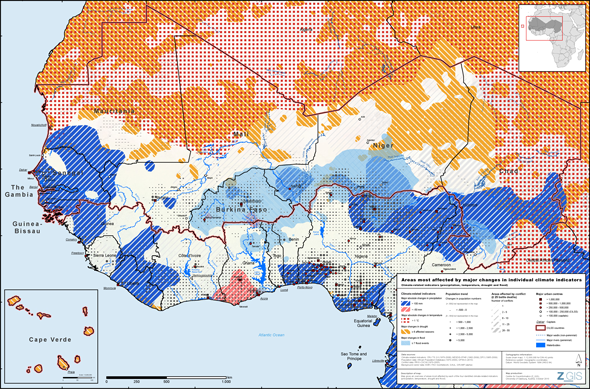

›A new set of maps from the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) identifies “climate hotspots” – areas vulnerable to instability exacerbated by climate change – in 17 sub-Saharan countries in and bordering the Sahel region. The maps reflect the fact that, more often than not, the impact of climate change on local populations is compounded by changes in migration, conflict, or both. According to Livelihood Security: Climate Change, Migration and Conflict in the Sahel, the UNEP report accompanying the maps, understanding “the exacerbating effect of changes in climate on population dynamics and conflict in the region” will be essential to developing successful adaptation strategies throughout the region.

UNEP’s maps analyze 40 years of data to pinpoint where the region’s most at-risk populations are located based on environmental, population, and conflict trends dating back to 1970. In a single map pinpointing the Sahel’s 19 hotspots, UNEP synthesizes subnational data from four environmental indicators over time – rainfall (from 1970 to 2006), temperature changes (1970 to 2006), drought (1982 to 2009), and flooding (1985 to 2009) – which are then layered on top of population trends (1970 to 2010) and conflict data (1970 to 2005) in order to identify the region’s most insecure areas.

Composite Vulnerability

At first glance, the map can appear hard to decipher; it is flooded with different colors and symbols, each indicating something different about the extent of climate change, migration, and conflict in the region. A Google Earth version of the map (available for download here) makes all this information easier to process by allowing users to select which indicators they want to see mapped out, cutting back on the number of lines, dots, colors, and pie charts the user has to decode.

Given the vast amount of the information being condensed into these maps, the report is a helpful and worthwhile read. For instance, eight hotspots are in places with growing populations and another seven are located in places that have experienced conflict; altogether, 4 of the 19 hotspots have both past conflict and growing populations. The report digs deeper into the confluence of climate, conflict, and migration by discussing case studies that highlight how the three intersect in local communities (at the same time, the report is careful to avoid suggesting that there is a causal relationship between the three issues.). In Niger, Nigeria, and Chad, for example, tensions have been mounting between northern pastoralists and southern farmers as each group has moved further and further afield in search of water and arable land to sustain their livelihoods.

Holes In the Data

While the hotspot maps include a wealth of information, the report makes clear that it is by no means exhaustive. Rising sea levels are, for instance, a major impending threat to coastal populations in the Sahel, but only the downloadable Google Earth map – not the hotspot map in the report or the Google Earth map as presented online – incorporates this factor. Compounded with a skyrocketing population in the coastal areas – the coast between Accra and the Niger delta is expected to be “an urban megalopolis of 50 million people” by 2020, according to the report – an increase in sea levels could have a huge impact on the region’s stability.

The report also readily admits that the datasets for population trends and conflict have shortcomings. Population data is largely based on censuses, which both the report and its data sources (UNEP’s African Population Database and the Gridded Population of the World, version 3) acknowledge can be inconsistent in their accuracy. Additionally, after 2000, population data is based on projections rather than estimates, which, as last year’s update from the UN Population Division showed, have often proven inaccurate, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa.

Regarding conflict, the UNEP report is straightforward in admitting its limits. The report lacks data on small-scale conflict (fewer than 25 battle deaths, following the Uppsala Conflict Data Program’s threshold that separates conflicts from lower-level violence), even as it acknowledges that such conflict is “often the first to occur” when climate change threatens communities’ access to resources and livelihoods.

Ultimately, however, these maps give valuable data on specific locations that are uniquely vulnerable to trends in population, climate, migration, and conflict. They add focus to the conventional wisdom that climate change will impact the region’s stability, and, taken together, the maps and the report provide a valuable resource for scholars and policymakers attempting to craft adaptation policies that take into consideration these complex links.

Sources: Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center at Columbia University’s Earth Institute, UNEP, Uppsala Conflict Data Program.

Image Credit: UNEP.

Showing posts from category security.