Showing posts from category environment.

-

El Niño, Conflict, and Environmental Determinism: Assessing Climate’s Links to Instability

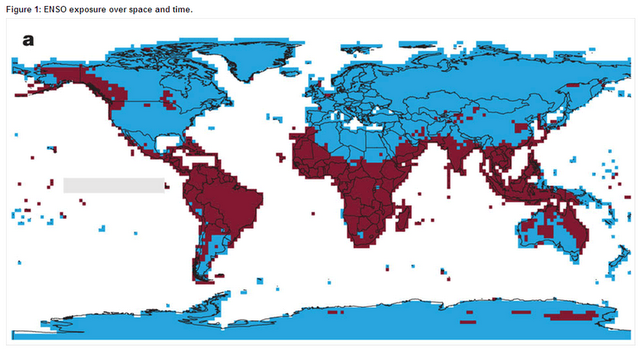

›October 5, 2011 // By Schuyler NullA recent Nature article on climate’s impact on conflict has generated controversy in the environmental security community for its bold conclusions about links between the global El Niño/La Niña cycle and the probability of intrastate conflict.

-

SXSW Eco Panel: Three Great Ideas That Won’t Be On the Rio+20 Agenda

›September 30, 2011 // By Schuyler Null South by Southwest (SXSW) – the popular music, film, and alternative showcase – is moving into the green space with its first ever “eco” conference, kicking off next week, October 4, with more than 50 panels on “solutions for a sustainable world.” There’s one in particular though you should tune into: “Three Great Ideas that Won’t Be On the Rio Agenda,” featuring Geoff Dabelko, director of the Wilson Center’s Environmental Change and Security Program; Roger-Mark De Souza, vice president of research and director of the climate program at Population Action International; and Aimee Christensen, CEO of Christensen Global Strategies.

South by Southwest (SXSW) – the popular music, film, and alternative showcase – is moving into the green space with its first ever “eco” conference, kicking off next week, October 4, with more than 50 panels on “solutions for a sustainable world.” There’s one in particular though you should tune into: “Three Great Ideas that Won’t Be On the Rio Agenda,” featuring Geoff Dabelko, director of the Wilson Center’s Environmental Change and Security Program; Roger-Mark De Souza, vice president of research and director of the climate program at Population Action International; and Aimee Christensen, CEO of Christensen Global Strategies.

The panel will feature discussion on three issues that will likely not be on the table at the Rio+20 UN Conference on Sustainable Development next year: integrated population, health, and environment development programs, climate adaptation as a path to peacebuilding, and how to get the private sector better involved in helping cope with climate change.

If you’re traveling down to Austin, “Three Great Ideas” is scheduled for Thursday, October 6 at 10am CST; if not, stay tuned for webcast information! -

Remembrance: Wangari Maathai, Nobel Peace Prize Winner, Linked Environment and Conflict

›September 26, 2011 // By Schuyler NullSad news today as Wangari Maathai, the first African woman and the first environmentalist to win the Nobel Peace Prize, has passed away in Nairobi. The Green Belt Movement, which Maathai founded in 1977, has planted over 30 million trees and advocates for what Maathai called the three essential components of a stable society: sustainable environmental management, democratic governance, and a culture of peace. [Video Below]

“Almost every conflict in Africa you can point at has something to do with competition over resources in an environment,” said Maathai during her visit to the Wilson Center in 2009:Unless you deal with the cause, you are wasting your time. You can use all the money you want for all the years you want; you will not solve the problem, because you are dealing with a symptom. So we need to go outside that box and deal with development in a holistic way.

Maathai’s message was molded from her experiences in Kenya and across sub-Saharan Africa in general. She was not shy about condemning African leaders and advocating for women in the political space. In ECSP Report 12, she wrote, “I come from a continent that has known many conflicts for a long time. Many of them are glaringly due to bad governance, unwillingness to share resources more equitably, selfishness, and a failure to promote cultures of peace.”

Importantly, though, Maathai advocated for addressing these issues in concert, not separately. She said at the Wilson Center:I can’t say, ‘Let us deal with governance this time, and don’t worry about the resources.’ Or, ‘Don’t worry about peace today, or conflicts that are going on; let us worry about management of resources.’ I saw that it was very, very important to use the tree-planting as an entry point.

A Message to the World

Some raised questions when Maathai won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2004 – the first awarded to someone from the environmental field – but the recognition was more than deserved, wrote Environmental Change and Security Program (ECSP) Director Geoff Dabelko on Grist:Maathai is on the front lines of the struggle over natural resources that fuels conflicts across the world. While there is no dramatic footage of tanks rumbling across borders or airplanes flying into buildings, the everyday fight for survival of those who depend directly on natural resources – forests, water, minerals – for their livelihoods is at the heart of the battle for peace and human security.

Maathai explained in Report 12 that she thought her winning of the prize was intended as a message to the world to “rethink peace and security.”

…

Elevating such a strong Southern voice – and one whose elephant’s skin bears the scars of the fight for peace – is a noble choice.

The Nobel Committee “wanted to challenge the world to discover the close linkage between good governance, sustainable management of resources, and peace,” she wrote. “In managing our resources, we need to realize that they are limited and need to be managed more sustainably, responsibly, and accountably.”

Sources: Grist, The New York Times.

Photo Credit: David Hawxhurst/Wilson Center. -

Carl Haub, Yale Environment 360

What If Experts Are Wrong On World Population Growth?

›September 22, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Carl Haub, appeared on Yale Environment 360.

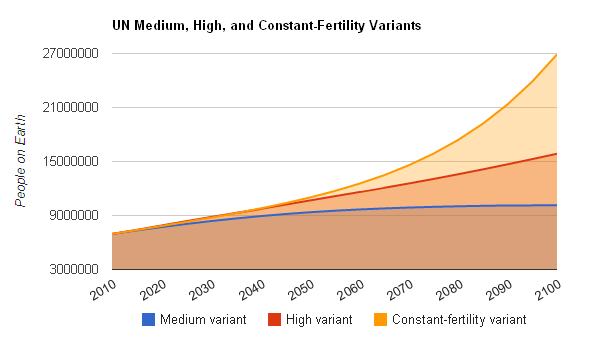

In a mere half-century, the number of people on the planet has soared from 3 billion to 7 billion, placing us squarely in the midst of the most rapid expansion of world population in our 50,000-year history – and placing ever-growing pressure on the Earth and its resources.

But that is the past. What of the future? Leading demographers, including those at the United Nations and the U.S. Census Bureau, are projecting that world population will peak at 9.5 billion to 10 billion later this century and then gradually decline as poorer countries develop. But what if those projections are too optimistic? What if population continues to soar, as it has in recent decades, and the world becomes home to 12 billion or even 16 billion people by 2100, as a high-end UN estimate has projected? Such an outcome would clearly have enormous social and environmental implications, including placing enormous stress on the world’s food and water resources, spurring further loss of wild lands and biodiversity, and hastening the degradation of the natural systems that support life on Earth.

It is customary in the popular media and in many journal articles to cite a projected population figure as if it were a given, a figure so certain that it could virtually be used for long-range planning purposes. But we must carefully examine the assumptions behind such projections. And forecasts that population is going to level off or decline this century have been based on the assumption that the developing world will necessarily follow the path of the industrialized world. That is far from a sure bet.

Continue reading on Yale Environment 360.

Image Credit: Data from UN Population Division, chart arranged by Schuyler Null. -

Broadening Development’s Impact: From Sustainability to Governance and Security

›John Drexhage and Deborah Murphy’s UN background paper, “Sustainable Development: From Brundtland to Rio 2012,” looks at how “sustainable development” has evolved since the 1987 Brundtland Report first brought the concept to the forefront of the international community’s attention. Drexage and Murphy write that climate change has become a “de facto proxy” for sustainable development and they offer various recommendations for how policymakers and institutions can better integrate social and economic issues into a sustainable development framework. Considering that “increasing consumption, combined with population growth, mean that humanity’s demands on the planet have more than doubled over the past 45 years,” the authors conclude that “the opportunity is ripe” to bring “real systemic change” to how the world thinks about – and acts on – sustainable development.

The World Bank’s World Development Report 2011 makes an argument for “bringing security and development together to put down roots deep enough to break the cycles of fragility and conflict.” The report gives an overview of the “interconnections among security, governance, and development” and offers recommendations on how understanding and addressing them can end cycles of violence. Just as Drexhage and Murphy point to population changes as a challenge for sustainable development, the World Bank notes that growing urbanization has “increased the potential for crime, social tension, communal violence, and political instability” locally while a threefold increase in refugees and internally displaced persons over the past 30 years has put strains on regional relations around the world. Though the report acknowledges that there’s no quick fix to any of these problems, the conclusion underlining the report’s findings is that “strengthening legitimate institutions and governance to provide citizen security, justice, and jobs is crucial to break cycles of violence.” -

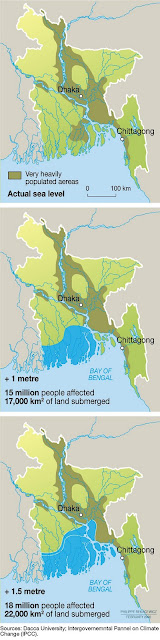

Perfect Storm? Population Pressures, Natural Resource Constraints, and Climate Change in Bangladesh

›Few nations are more at risk from climate change’s destructive effects than Bangladesh, a low-lying, lower-riparian, populous, impoverished, and natural disaster-prone nation. The UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates that by 2050, sea levels in Bangladesh will have risen by two to three feet, obliterating a fifth of the country’s landmass and displacing at least 20 million people. On September 19, the Wilson Center’s Asia Program, with assistance from ECSP and the Comparative Urban Studies Project, hosted a conference that examined Bangladesh’s imperiled environmental security.

Climate Change and Population

The first panel focused on manifestations, drivers, and risks. Ali Riaz addressed the threat of climate refugees. Environmental stress, he said, may produce two possible responses: fight (civil conflict or external aggression) or flight (migration). In Bangladesh, the latter is the more likely outcome. Coastal communities, overwhelmed by rising sea levels and flooding, could migrate to Bangladesh’s urban areas or into neighboring India. Both scenarios pose challenges for the state, which already struggles to provide services to its urban masses and has shaky relations with New Delhi.

Mohamed Khalequzzaman examined Bangladesh’s geological vulnerability in the context of climate change. In a deltaic nation like Bangladesh, he explained, sedimentation levels must keep up with rates of sea level rise to prevent the nation from drowning. However, sediment levels now fall below 5 millimeters (mm) per year – short of the 6.5 mm Khalequzzaman calculates are necessary to keep pace with projected sea level rises. He lamented the nation’s tendency to construct large dams and embankments in the Bengal Delta, which “isolate coastal ecosystems from natural sedimentation,” he said, and result in lower land elevations relative to rising sea levels.

Adnan Morshed declared that Bangladesh’s geographic center – not its southern, flood-prone coastal regions – constitutes the nation’s chief climate change threat. Here, Dhaka’s urbanization is “destroying” Bangladesh’s environment, he said. Impelled by immense population growth (2,200 people enter Dhaka each day) and the need for land, people are occupying “vital wetlands” and rivers on the city’s eastern and western peripheries. “Manhattan-style” urban grid patterns now dominate wetlands and several rivers have become converted into land. Exacerbating this urbanization-driven environmental stress are highly polluting wetlands-based brickfields (necessary to satisfy Dhaka’s construction needs) and city vehicular gas emissions.

Adaptation Responses

The second panel considered possible responses to Bangladesh’s environmental security challenges. Roger-Mark De Souza trumpeted the imperative of more gender-inclusive policies. Environmental insecurity affects women and girls disproportionately, he said. When Bangladesh is stricken by floods, females must work harder to secure drinking water and to tend to the ill; they must often take off from school; and they face a heightened risk of sexual exploitation – due, in great part, to the lack of separate facilities for women in cyclone shelters. He reported that such conditions have often led to early forced marriages after cyclones.

Shamarukh Mohiuddin discussed possible U.S. responses. On the whole, American funding for global climate change adaptation programs has lagged and initiatives that are funded often focus more on short-term mitigation (such as emissions reductions) rather than adaptation. She recommended that Washington’s Bangladesh-based adaptation efforts be better coordinated with those of other donors.

Mohiuddin also suggested that to convey a greater sense of urgency, Bangladesh’s climate change threats should be more explicitly linked to national security – and particularly to how America’s strategic ally, India, would be affected by climate refugees fleeing Bangladesh.Philip J. DeCosse highlighted Bangladeshi government success stories in the famed Sundarbans – one of the world’s largest mangrove forests. Officials have banned commercial harvesting in some areas of the forests and shut down a highly polluting paper mill. He also praised civil society and the media for bringing attention to the Sundarban’s environmental vulnerability. As a result of efforts such as these, the Sundarbans are “coming back,” he said, with mangrove species growing anew. Thanks to a range of actors – from the forestry department to civil society – these forests are also now being “governed more than managed,” said DeCosse.

The Sundarbans – click to view larger map.

DeCosse’s fellow panelists identified additional hopeful signs. Morshed shared a photograph of a green, pristine park in Dhaka. De Souza underscored how family planning programs have worked in Bangladesh in the past, with fertility rates declining considerably in recent years, and several speakers spotlighted efforts by civil society and the media to bring greater attention to Bangladesh’s environmental security imperatives.

Nonetheless, major challenges remain, and panelists offered a panoply of recommendations. Khalequzzaman called for a major geological study of soil loss and siltation. De Souza implored Bangladesh to ensure that women’s roles and family planning considerations are featured in climate change negotiations and adaptation policies. Morshed advocated for imposing urban growth boundaries and enhancing public transport in cities. And several speakers spoke of the need to pursue more effective natural-resource-sharing arrangements with India. Ultimately, in the words of De Souza, it may not be possible to eliminate Bangladesh’s “perfect storm” – but much can be done to calm it.

Event ResourcesMichael Kugelman is a program associate with the Wilson Center’s Asia Program.

Sources: UN.

Photo/Image Credit: “Precarious Living, Dhaka,” courtesy of flickr user Michael Foley Photography; “Impact of Sea Level Rise in Bangladesh,” courtesy of UNEP; and the Sundarbans courtesy of Google Maps. -

Loren Landau: We Need to Move Beyond Traditional Views of Migration

› Addressing the role of subnational actors, from local governments to mining companies, is increasingly critical to understanding migration, said Loren Landau, director of the African Center for Migration and Society at the University of the Witwatersrand, in an interview with ECSP. These actors frequently exert more influence than national governments over human resources because they control the “space in which people live, the space in which they produce,” Landau said.

Addressing the role of subnational actors, from local governments to mining companies, is increasingly critical to understanding migration, said Loren Landau, director of the African Center for Migration and Society at the University of the Witwatersrand, in an interview with ECSP. These actors frequently exert more influence than national governments over human resources because they control the “space in which people live, the space in which they produce,” Landau said.

Migration is most frequently seen as an aberration or a temporary coping mechanism, but this conception is outdated. According to Landau, “especially as rural livelihoods become less viable, movement will be the norm.”

Local and global actors must recognize that “people are moving, and they are moving to a whole range of new places,” he said. These new places will need attention and resources, but we will need to move beyond traditional views of migration in order to respond to the challenge. -

Jan Eliasson, Huffington Post

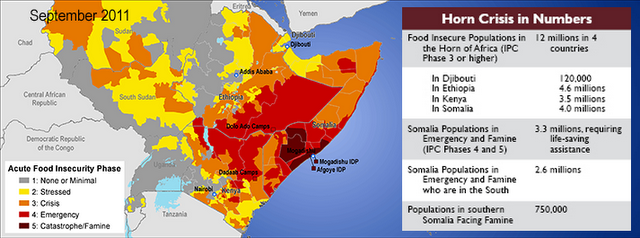

What Somalia Teaches Us: Sanitation, Health, and Conflict

›September 15, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Jan Eliasson, appeared on Huffington Post.

The confirmation of cholera deaths in Somalia offers a chilling reminder of what happens when there is no safe water and inadequate sanitation. The refugee crisis in Somalia is fueled by the worst drought in the horn of Africa in over 60 years.

This humanitarian disaster is a glaring example of the international community’s failure to uphold basic needs and rights of some of our planet’s most vulnerable people. As we struggle to respond to this humanitarian catastrophe, we must remember that Somalis are in need of more than access to food, but also safe water, sanitation, shelter, and healthcare.

For many of Somalia’s poorest citizens, who have walked for days and miles, drinking contaminated water, and staying in crowded camps, deadly diseases including cholera may be a tragic but predictable end result. Up to 100,000 people have crowded into Mogadishu, seeking shelter, food, and water. More arrive each day in Mogadishu and in overflowing camps in neighboring Kenya.

Experts estimate that more than 29,000 children under the age of five have already died from the combination of drought, famine, and illness. Diarrhea is on the rise in overcrowded shelters where there is a shortage of safe water and large numbers of weak and malnourished children. These conditions provide a breeding ground for infectious diseases, including measles, cholera and pneumonia. On August 18th, Tarik Jasarevic, a spokesperson for the World Health Organization, said, “We don’t see the end of it.”

Continue reading on Huffington Post.

Sources: AP, The New York Times, UN.

Image Credit: “The Horn of Africa food security crisis in numbers,” courtesy of the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) and USAID.