Showing posts from category security.

-

Helping Hands: An Integrated Approach to Development

›Originally featured in the Wilson Center’s Centerpoint, June 2011.

“At the moment, the agendas of the growing population of people and the environment are too separate. People are thinking about one or the other,” said Sir John Sulston, Nobel laureate and chair of the Institute for Science, Ethics, and Innovation at the University of Manchester, in an interview with the Environmental Change and Security Program (ECSP).

“People argue about, ‘Should we consume less or should we have fewer people?’ The point is it’s both. We need to draw it together. It’s people and their activities.”

Many who research and work on population, health, and environment (PHE) issues are increasingly advocating integrated solutions. Such issues as population growth, natural resource management, and food security, are interrelated challenges that, if addressed concurrently, likely will yield better results and community trust.

With this notion in mind, ECSP launched the five-year HELPS (health, environment, livelihoods, population, and security) project in October 2010. The project focuses on integrated PHE programs and demographic security linkages. HELPS also looks at population’s links to global environmental priorities, media coverage of population, and related issues like gender, youth, and equity.

Funded by USAID’s Office of Population and Reproductive Health through its IDEA (Informing Decision-makers to Act) grant, the HELPS project builds on ECSP’s 14-year history of exploring nontraditional security issues.

Population-Environment Connection

A February event in the HELPS series featured Sir John Sulston, who said dialogue between population and environmental communities has received renewed attention and is reappearing on national agendas.

The Royal Society’s People and the Planet study, which will be completed by early 2012, will “provide policy guidance to decision-makers as far as possible” and aims to facilitate dialogue, he said. The HELPS Project is helping the working group gather evidence of population-environment connections and to identify solutions.

“What we should be aiming to do is to ensure that every individual on the planet can come to enjoy the same high quality of life whilst living within the Earth’s natural limits,” said Sulston. People are happier, healthier, and wealthier than ever before, according to human development indexes. But, Sulston said, 200 million women worldwide have an unmet need for family planning, ecosystems are degraded, biodiversity has decreased, and there are widespread shortages of food and water.

“Many times we tackle different development challenges through single sector programs: health programs, agriculture programs, water programs. Those single sector approaches can make sense,” said ECSP Director Geoff Dabelko on the Wilson Center’s Dialogue television program. “But, of course, poor people are facing all those life and death challenges at once. We have to find ways to help them meet those challenges together in an integrated fashion.”

On the same program, Roger-Mark De Souza, vice president for research and director of the Climate Program for Population Action International, said the drive for integrated development stems from the communities being served, not necessarily from outside aid groups. “We’ve seen that there’s a greater impact because there’s longer sustainability for those efforts that have an integrated approach,” he said. “There’s a greater understanding and a greater appreciation of the value that [PHE] projects bring.”

At an April 7 ECSP event, De Souza said rural communities in developing countries understand that high population growth rates, poor health, and environmental degradation are connected. An integrated approach to development, he said, is a “cost-effective intervention that we can do very easily, that responds to community needs that will have a huge impact that’s felt within a short period of time.”

Proponents of integrated development face significant barriers, but the tide may be turning. To fully harness this momentum, former ECSP Senior Program Associate Gib Clarke argues in his FOCUS brief, “Helping Hands: A Livelihood Approach to Population, Health, and Environment Programs,” that the PHE community must solidify its research base, reach out to new partners, and push for flexible funding and programming. He suggested changing the name PHE to HELP – health, environment, livelihoods, and population. By adding livelihoods, the glue that binds population, health, and the environment, he said, the HELP moniker might broaden its appeal to new donors and practitioners.

Case Study: Madagascar

In Madagascar, a key country for integrated PHE programs, “today’s challenges are even greater than those faced 25 years ago,” said Lisa Gaylord, director of program development at the Wildlife Conservation Society, at a March 28 Wilson Center event. As the country’s political situation has deteriorated since 2009, the United States and other donors pulled most funding, and some PHE programs were forced to discontinue environmental efforts.

But other PHE programs are expanding: Based in southwestern Madagascar, the Blue Ventures program began as an ecotourism outfit, said Program Coordinator Matt Erdman, but has since grown to incorporate marine conservation, family planning, and alternative livelihoods. A major challenge is its rapidly growing population, which threatens the residents’ health and food security, as well as the natural resources on which they depend. More than half the island’s population is younger than 15, and the infant and maternal mortality rates are high, Erdman said.

In response, Blue Ventures set up a family planning program. The program uses a combination of clinics, peer educators, theater presentations, and sporting events, such as soccer tournaments, to spread information about health and family planning. The HELPS project will soon publish a Focus brief on Blue Ventures’ family planning efforts, titled: “To Live with the Sea.”

Erdman said, “If you have good health, and family size is based on quality, families can be smaller and [there will be] less demand for natural resources, leading to a healthier environment.”

Demographic Security

A country’s age structure can pose a challenge, said Jennifer Dabbs Sciubba, the Mellon Environmental Fellow with the Department of International Studies at Rhodes College, at a March 14 Wilson Center event. Countries with a large percentage of people younger than 30 “are [much] more likely to experience civil conflict than states with more mature age structures.”

Tunisia’s recent revolution, Sciubba said, could be understood as a “story about demography.” Countries with transitional age structures, such as India, Brazil, and South Africa, face different security challenges. With a majority of their populations between 15 and 60 years old, more people are contributing to the economy than are taking away, which could bolster these countries economically and politically. Global institutions will have to reform and include these countries, she advised, “or else become irrelevant.”

“Understanding population is critical to our success in being able to prevent conflict, and also managing conflict and crises once we’re involved,” said Kathleen Hicks, Deputy Undersecretary at the Department of Defense (DOD). However, the DOD does not “treat demographics as destiny,” she said, but instead as “one of several key trends, the complex interplay of which may spark or exacerbate future conflicts.”

Demography can also help predict political trends. In 2008, demographer Richard Cincotta predicted that between 2010 and 2020 the states along the northern rim of Africa – Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt – would each reach a demographically measurable point where the presence of at least one liberal democracy among the five would be probable. Recent months have brought possible first steps to validate that prediction.

Mathew Burrows, counselor at the National Intelligence Council, said Cincotta’s work demonstrates that “the demographic tool is essential” to analysts and policymakers. “There is a real appetite among policymakers” for understanding demography, he said, because it gives them more structure than political science narratives.

Yemen is another example of this trend. In March, tens of thousands of youth-led demonstrators demanded that their president resign. While numerous factors have sparked the “Arab Spring,” one driving force is Yemen’s dire demographic and environmental situation. Some experts say Yemen may be the first country to run out of groundwater. The average Yemeni woman has more than five children, and 45 percent of its population is below age 15. On May 18, Yemeni and international experts discussed these issues at the Wilson Center. Upcoming HELPS events include daylong conferences on Afghanistan and Nigeria.

There are solutions that can break the links between “youth bulges” and insecurity. In a recent video interview discussing the connection between demography and civil conflict, Elizabeth Leahy Madsen, a senior research associate at Population Action International, said, “Policies that have a major impact over time are ensuring education, especially for girls, and providing employment opportunities to the large and growing numbers of young people today.”

Dana Steinberg is the editor of the Wilson Center’s Centerpoint.

Photo Credit: Blue Ventures in Madagascar, courtesy of Garth Cripps. -

Global Climate Change Vulnerability and the Risk of Conflict

›In a study from the Center for Sustainable Development at Uppsala University in Sweden titled “Climate Change and the Risk of Violent Conflicts in Southern Africa,” authors Ashok Swain, Ranjula Bali Swain, Anders Themnér, and Florian Krampe examine the potential for climate change and variability to act as a “threat multiplier” in the Zambezi River Basin. The report argues that “socio-economic and political problems are disproportionately multiplied by climate change/variability.” A reliance on agriculture, poor governance, weak institutions, polarized social identities, and economic challenges in the region are issues that may combine with climate change to increase the potential for conflict. Specifically, the report concludes that the Matableleland-North Province in Zimbabwe and Zambezia Province in Mozambique are the areas in the region most likely to experience climate-induced conflicts in the near future.

The “Climate Vulnerability Monitor 2010: The State of the Climate Crisis,” published by Madrid-based DARA and the Climate Vulnerable Forum, is a comprehensive atlas of climate change vulnerability around the world. The report examines country vulnerability in four impact areas – health, weather disasters, habitat loss, and economic stress – and compares current levels of vulnerability with those expected in 2030. Of the 184 assessed countries, nearly all registered high vulnerability to at least one impact area. The report estimates that there are 350,000 “climate-related deaths” each year, almost 80 percent of which are children living in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Finally, the report features an overview of climate change basics, country profiles, and reviews on the effectiveness of several climate adaptation methods. -

Yemen Beyond the Headlines: Governance, State Capacity, and the U.S.

›Part two of the “Yemen Beyond the Headlines: Population, Health, Natural Resources, and Institutions” event, held at the Wilson Center on May 18.

“Moving beyond Ali Abdullah Saleh has proved to be very challenging, not only for the Yemeni people, but for the neighboring countries and for the international community as a whole,” said former U.S. Ambassador to Yemen Edmund Hull, one of a number of speakers on governance and future challenges during the all-day conference, “Yemen Behind the Headlines: Population, Health, Natural Resources, and Institutions,” at the Woodrow Wilson Center. [Video Below]

Don’t Throw Out the Good With the Bad

Yemen’s protest movement is different than those of Egypt or Tunisia because neighboring countries, such as those in the Gulf Cooperation Council, are actively involved. “[They] don’t have the luxury of saying this is a purely Yemeni affair,” said Hull. “They have to identify where their national interests are and then they have to come up with a legitimate and effective way of protecting those interests.” Included in those national interests is dealing with the presence of Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.

But, Hull said, “It would be a shame if, as part of this revolution, what was good in Yemen gets tossed out with what was bad.” Among the institutions that should be protected are the Social Fund for Development, a government development initiative designed to reduce poverty , and the Central Security Forces, “still a very necessary institution and one that has to be protected if other challenges in Yemen are to be met,” he said.

“It’s a mistake to over-focus on the end of a regime – yes, it’s important to get a transfer of power, but I would argue [that it is] equally important to institutionalize the forces that have led to this, as a safeguard against the counter revolution and as an impetus to meeting those many, many political challenges that Yemen faces.”

Going forward, Hull said that elections will be key: Yemen had good electoral experiences in 2003 and 2006 but the system has since suffered some “backsliding,” he said. He also emphasized the importance of letting the youth participate, protecting social networking systems and NGOs, instituting legal requirements to promote transparency, and freeing up and protecting the media. “Unless you have a media spotlight, abuses are going to accumulate,” he said.

Not a “Basket-Case”

“Yemen is not a basket case,” said Charles Schmitz, an associate professor at Towson University. “There have been substantial achievements that I think we need to take into account.” Among these achievements, he highlighted Yemen’s growth in life expectancy, literacy rates, and gross domestic product. The country’s population growth rate has also slowed over the past two decades, though its total fertility rate remains one of the highest in the region.

These gains were fuelled by two resource booms, Schmitz explained: mainly, remittances from the construction boom in the 1970s and oil production. However, oil production dropped off dramatically after peaking around 2001, and remittances have not been able to keep up with the growth of the economy.

“Yemen is in a very severe crisis,” Schmitz said. “The oil has stopped… the balance of payments has been going negative for the last couple of years… and the government appears to be dipping into the central bank.” As a result, he said there is a “very real” possibility of the currency – the riyal – collapsing. The currency represents trust in the government, of which there is none right now, he said.

An Opportunity for New Thinking

“The key variable to the future of the Yemeni economy is state capacity, and this is something Yemen has not done well thus far, largely because of the political crisis,” Schmitz said.

“I think we must be attuned to the reality around us,” said Jeremy Sharp, a specialist in Middle Eastern affairs with the Congressional Research Service. “Quite frankly, Yemen needs a lobby in this country. Yes we have a tight budget environment, but it’s also an opportunity for new thinking.”

“The degree and extent of U.S. engagement with Yemen…is based primarily on the perceived terrorist threat there,” said Sharp. “Our policy toward Yemen always seems to be one horrific terrorist attack away from public outcries for deeper U.S. involvement – i.e., military involvement.”

A Cycle of Transitions?

“We may be looking at cycles of transition in Yemen over the coming decades,” said Ginny Hill, an associate fellow with the Middle East and North Africa Programme at Chatham House. “Stable political settlements take time.” The street protestors are not going to get what they want in the short term, “but just two or three of them sitting in government or being involved in the negotiation process… is going to change the dialogue in Yemen,” she said.

The United States has difficult questions to answer, said Sharp: Who will control Yemen’s security forces down the line? How will the next leader deal with the U.S.-Yemen partnership? Will power be fragmented between civilian and military leaders? Will the next leader play the nationalist card and reduce cooperation with the United States to bolster their own public standing?

“In the absence of the degree of engagement that we need, the [U.S. government] aims high rhetorically,” said Sharp. “We speak about these things while pursuing our own national security goals on the ground. Perhaps this path is unsustainable and events will force the U.S. to pay even more attention to Yemen. Or perhaps we will continue to muddle along this path and never quite reach the brink, precipice, or impending crisis that is so routinely predicted in the media.”

See parts one and three of “Yemen Beyond the Headlines: Population, Health, Natural Resources, and Institutions” for more from this Wilson Center event.

Sources: UNICEF, World Bank.

Photo Credit: “Even small children…,” courtesy of flickr user AJTalkEng. -

Inaugural Lee Hamilton Lecture at the Wilson Center

Admiral Mullen: “Security Means More Than Defense”

›Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Admiral Mike Mullen delivered the inaugural talk in the Lee Hamilton Lecture Series on Civil Discourse and Democracy at the Wilson Center yesterday where he spoke on the importance of “taking the long-view” on U.S. engagement with the world and the changing field of 21st century geopolitics.

Mullen, whose aides, Captain Wayne Porter and Colonel “Puck” Mykleby, wrote the recently launched Mr. Y paper on a new national strategic narrative, echoed many of the same sentiments.

“[The Mr. paper] has some interesting things to say about how we are seeing a shift away from 20th century concepts of power and control to that of promoting strength and influence,” Mullen said. “Frankly, in this small, flatter, and faster world, I think any nation that believes it can, in a very clinical way, control events does so at their own peril.”

“The narrative also happens to share my long-held belief that we must remain engaged internationally if we wish to pursue the world that our children [and] our grandchildren deserve,” he continued:As challenging as engaging others with different views may be, the alternative of abandoning these partners in these regions is far worse. We’ve gone down that road before, and it is one that leads to isolation and resentment, ultimately making our nation less secure as we deceive ourselves into believing that ignoring these challenges will somehow make them go away.

Mullen also agreed with the Mr. Y authors’ view on adopting a more holistic view of national security:

…

Until we restore a sense of hope in these challenged regions, we will see again and again that security without prosperity is ultimately unsustainable.Wayne and Puck put it well when they said we must recognize that security means more than defense. And sustaining security requires adaptation and evolution, the leverage of converging interests, and interdependencies. We must accept that competitors are not necessarily adversaries and that a winner does not demand a loser.

The military’s energy initiatives are an important focus as well, Mullen said. “We’re the biggest consumer of energy in the U.S. government…and I don’t think we’ll ever get to a position where that’s not the case, but we certainly ought to recognize that and figure out a way to do it more effectively, efficiently, and at a much reduced cost.”

What we learned in Iraq is “there were too many people getting killed in long convoys,” Mullen said. The Marines were able to adapt to that threat by developing self-contained green cooling kits, and “that’s where we’re headed,” he said. “Our focus on and investments in the green world has taken off.”

“Now it is really mainstream: The service chiefs, combatant commanders, [they] talk about it,” Mullen continued. “There are investments being made, both from an S&T; standpoint – science and technology – as well as research and development.”

Read the transcript in its entirety here for the Chairman’s remarks on the continued importance of the UN, G-20, and NATO; the short-term intractability of challenges in Iran and North Korea; the rise of China; continued American military dominance; the defense budget; and the Arab Spring, which he called the “most significant change afoot in the world today.”

Photo Credit: Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Admiral Mike Mullen, courtesy of David Hawxhurst/Wilson Center. -

“The Second Front in the War on Terror”

USAID, Muslim Separatists, and Politics in the Southern Philippines

›For some years after the terrorist attacks of 9/11, the existence of violent Muslim separatists on the southern Philippine island of Mindanao gave U.S. officials significant cause for concern. In 2005, for example, the U.S. embassy charge d’affaires to the Philippines, Joseph Mussomeli, told reporters that “certain portions of Mindanao are so lawless, so porous…that you run the risk of it becoming like an Afghanistan situation. Mindanao is almost, forgive the poor religious pun, the new Mecca for terrorism.” During the Bush administration, officials referred to the region as a “second front” in the War on Terror: the region was once seen as a “new Afghanistan” that “threatened to become an epicenter of Al Qaeda.” [Video Below]

Nevertheless, as noted by Wilson Center Fellow Patricio Abinales at an Asia Program event on May 11, U.S. efforts to co-opt and pacify separatist guerrillas have proven remarkably successful in some areas of the islands. Some commentators have highlighted the role of the U.S. military in bringing a relative sense of security to troubled regions, noting that Mindanao presents a “future model for counterinsurgency.” However, Abinales’s research shows the military activities have had little effect, often because troops are stationed far from potential areas of conflict. Instead, it is the civilian side of the American presence that has dampened conflict in the war zones of the southern Philippines.

Abinales specifically explored the factors behind the success of the U.S. Agency for International Development’s (USAID) Growth with Equity in Mindanao (GEM) program in demobilizing and reintegrating 28,000 separatist guerrillas of the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF), as well as the long-term political consequences of this accomplishment.

“Arms to Farms”

Usually, USAID programs are organized on the basis of grants for specific and limited projects. In contrast, GEM arose as a long-term umbrella organization that oversees the disbursement and management of American funding across a number of long-term projects. Coordinators are trained directly in Mindanao and are encouraged to “go native,” living in the area and becoming part of the community. GEM prioritizes cultural understanding, respect for community leaders, an appreciation of the important role that women play in local societies, and sensitivity to potential divisions within separatist groups and their security concerns vis-à-vis the Philippine government.

There has often been a general tendency for aid organizations to associate the demobilization of warring groups with disarmament. While Philippine officials on Mindanao have sometimes tried this approach, cash-for-guns amnesty schemes have opened up opportunities for corruption and have not been particularly effective. Understanding that one of the major concerns of guerrilla rebels is exploitation by corrupt government officials, GEM established an “Arms to Farms” scheme, whereby Muslim rebels are trained to engage in agriculture, but are not encouraged to put away their weapons. In this way, the program keeps potential guerrillas and Al Qaeda recruits busy with legitimate and peaceful economic activity, while it assuages their concerns about the threat from corrupt government officials, who may otherwise take the fruits of agricultural labor by force.

In fact, Abinales noted that one of the keys to GEM’s success is that the organization has never submitted to the official local authorities, and has largely been allowed a free reign by Manila to conduct its activities on Mindanao. It is precisely because the state has not been successful in delivering welfare regimes which provide stability to the area that GEM is seen as an alternate source of development and security in the region. Moreover, because of GEM’s activities, other American officials are allowed relatively free access, and are even welcomed into areas where the authority of the Philippine government holds no sway. Most of GEM’s activities are conducted with the MNLF, which has maintained its own official treaties and agreements with Manila since the 1970s. However, the American organization is beginning to enter the territory of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, a splinter group of the MNLF that rejects relations with the national government outright, but one whose leaders are jealous of the development gains the MNLF has made under GEM.

Abinales was quick to point out that although GEM’s activities have been successful, they are tailor-made to specific circumstances. It is therefore difficult to present them as a generalized model that can be applied to other separatist conflicts. Nevertheless, Abinales’s work suggests that government agencies working on counterinsurgency efforts elsewhere might do well to examine the benefits of the flexible civilian approaches to conflict resolution formed with a deep understanding of the concerns of the specific communities involved.

Bryce Wakefield is program associate with the Asia Program at the Woodrow Wilson Center. -

Ten Billion: UN Updates Population Projections, Assumptions on Peak Growth Shattered

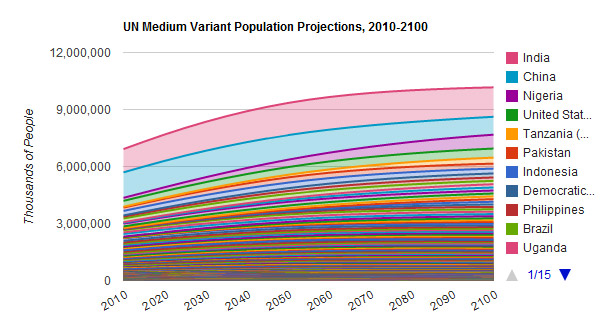

›May 12, 2011 // By Schuyler NullThe numbers are up: The latest projections from the UN Population Division estimate that world population will reach 9.3 billion by 2050 – a slight bump up from the previous estimate of 9.1 billion. The most interesting change however is that the UN has extended its projection timeline to 2100, and the picture at the end of the century is of a very different world. As opposed to previous estimates, the world’s population is not expected to stabilize in the 2050s, instead rising past 10.1 billion by the end of the century, using the UN’s medium variant model.

-

Isobel Coleman, Council on Foreign Relations

Report: Family Planning and U.S. Foreign Policy

›May 10, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this brief, by Isobel Coleman of the Council on Foreign Relations, is based on the report, Family Planning and U.S. Foreign Policy: Ensuring U.S. Leadership for Healthy Families and Communities and Prosperous, Stable Societies, by Isobel Coleman and Gayle Lemmon.

Click here for the interactive version (non-Internet Explorer users only).

U.S. support for international family planning has long been a controversial issue in domestic politics. Conservatives tend to view family planning as code for abortion, even though U.S. law, dating to the 1973 Helms Amendment, prohibits U.S. foreign assistance funds from being used to pay for abortion. Indeed, increased access to international family planning is one of the most effective ways to reduce abortion in developing countries. Investments in international family planning can also significantly improve maternal, infant, and child health. Support for international voluntary family planning advances a wide range of vital U.S. foreign policy interests – including the desire to promote healthier, more prosperous, and secure societies – in a cost-effective manner.

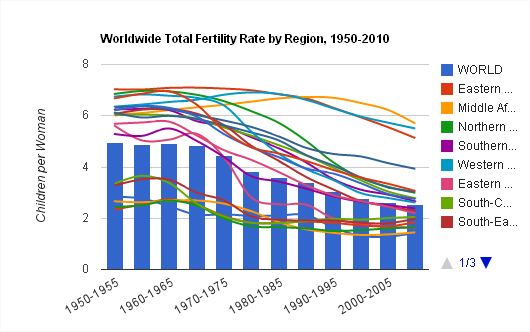

Saving Lives of Mothers and Children

More than half of all women of reproductive age in the developing world, some 600 million women, use a form of modern contraception today, up from only 10 percent of women in 1960. This has contributed to a global decline in the average number of children born to each woman from more than six to just over three. Despite these gains, an estimated 215 million women globally – particularly in sub-Saharan Africa and southern Asia – are sexually active but are not using any contraception, even though they want to avoid pregnancy or delay the birth of their next child. With the world’s population poised to cross the seven billion mark later in 2011, and expected to grow by nearly 80 million people annually for several more decades, global unmet need for family planning is likely to increase.

Studies have shown that contraception could reduce maternal deaths by a third, from approximately 360,000 to 240,000; reduce abortions in developing countries by 70 percent, from 35 million to 11 million; and reduce infant mortality by 16 percent, from 4 million to around 3.4 million.

For a woman in the developing world, the lifetime risk of dying from pregnancy is still one of the greatest threats she will face. In developed countries, 1 out of 4,300 women will lose her life as a consequence of pregnancy, compared to sub-Saharan Africa, where that figure soars to 1 in 31, and Afghanistan, where the lifetime risk of dying from pregnancy is 1 out of 7.

Unsafe abortions are one factor contributing to high maternal death rates. As of 2008, 47,000 abortion-related maternal deaths occur annually, accounting for 13 percent of all maternal deaths. Filling the unmet need for modern family planning would lead to a reduction in mistimed pregnancies and a significant decline in abortions and abortion-related health complications. In 2000 alone, if women who wished to postpone or avoid childbearing had access to contraception, approximately 90 percent of global abortion-related and 20 percent of obstetric-related maternal deaths could have been averted.

Maternal mortality has a devastating and irreversible effect on children and families. Indeed, countries with the highest maternal mortality rates also experience the highest rates of neonatal and childhood mortality. When a mother dies, her surviving newborn’s risk of death increases to 70 percent.

Family planning presents an opportunity to curb maternal and under-five deaths not simply by giving women of all ages the ability to determine their family size, but by enabling women to delay pregnancy until at least age 18 and to space and plan their births. In this way, modern contraceptive methods help women avoid high-risk pregnancies. Studies suggest that short pregnancy intervals (when the pregnancy occurs less than twenty-four months after a live birth) are associated with an increased risk of maternal and under-five mortality. In fact, if all mothers were to wait at least 36 months to conceive again, it is estimated that 1.8 million deaths of children under five could be prevented annually.

Enhancing International Security

While much of the developed world is experiencing population stability or even decline, many countries in the developing world continue to see rapid population growth. Population imbalances have emerged as a serious issue affecting economic opportunity, global security, and environmental stability. Ongoing civil conflicts, radicalism, weak governance, and corruption are endemic problems for many fragile states. While high fertility rates are not the cause of their problems, they do complicate the challenges these countries face in trying to reduce poverty, achieve per capita income growth, provide education and productive opportunities for youth, and address increasing shortages of natural resources.With the world’s population poised to cross the 7 billion mark later in 2011, and expected to grow by nearly 80 million people annually for several more decades, global unmet need for family planning is likely to increase.

Yemen, for example, has the highest rate of unmet need for family planning of any country. Its population has doubled in less than 20 years, and it has the world’s second-youngest population. High fertility – around six children per woman – taxes Yemen’s infrastructure, education and health systems, and environment. In addition, its labor force is growing at a pace much faster than the growth of available jobs, resulting in high youth unemployment. Increasing access to family planning would help improve Yemen’s long-term prospects for achieving per capita growth and stability. Conversely, continued high fertility rates will only deepen Yemen’s current crises.

Many countries experiencing fast population growth – like Yemen – do not have the capacity to harness the potential of their young populations. In these cases, high fertility rates can lead to a vicious cycle of poverty at the community, regional, and national levels. Rapidly growing populations are also more prone to outbreaks of civil conflict and undemocratic governance. Eighty percent of all outbreaks of civil conflict between 1970 and 2007 occurred in countries with very young populations. Demographers have shown that the statistical likelihood of civil conflict consistently decreases as countries’ birth rates decline.

Countries with the highest population growth rates face real resource constraints, particularly arable land and clean water. As of 2010, 40 percent of populations in more than 35 countries have insufficient access to food, with the largest concentration in central and eastern sub-Saharan Africa. Given that many of these food-insecure countries will continue to experience significant population growth in decades ahead, malnutrition will remain a challenge.

Continue reading at the Council on Foreign Relations or download the full report, Family Planning and U.S. Foreign Policy: Ensuring U.S. Leadership for Healthy Families and Communities and Prosperous, Stable Societies.

Isobel Coleman is a senior fellow for U.S. foreign policy; director of the Civil Society, Markets, and Democracy Initiative; and director of the Women and Foreign Policy Program at the Council on Foreign Relations.

Sources: Council on Foreign Relations, Population Action International, Population Reference Bureau, UNFPA, World Health Organization.

Chart Credit: Arranged by Schuyler Null, data from UN Population Division, World Population Prospects, 2010 Revision. -

A New Security Narrative: What’s America’s Story for the 21st Century?

›We rarely had to question our place in the world during World War II or the Cold War when good guys and bad guys were easier to identify. A clear narrative, whether in the form of opposing Hitler or containing the spread of “The Evil Empire,” fueled our sense of global mission. Sure there were disagreements, but the big picture (and the big enemy) loomed large.

Our sense of realities, large and small, begins with the stories that frame our understanding of the events around us. The fall of the USSR took the wind out of the sails of our mythic sense of purpose. We were still “us,” but we now lacked a “them.”

A security narrative often emerges from our collective sense of threat assessment. It’s not only about what we stand for, but also what we stand against. On that fateful day of September 11, 2001, many believed that we had found the enemy that would provide the story lacking from our national security narrative since the fall of the Soviet empire. But an ill-defined foe lacking a nation-state home has only contributed to our post-Cold War drift. When we ask ourselves why we are committing military might in Libya (or Afghanistan, or Iraq), we’re really asking bigger questions. What is our purpose in the world? What is the story that defines our friends and our foes? And what does that story tell us about when to sit back or step up? When to watch or when to act?

The lack of a storyline also gives those who hate us the opportunity to define us as evil. So it becomes ever more urgent to start the conversation and to provide a non-partisan forum for what is bound to be a difficult deliberation. When Jane Harman left Congress to accept the leadership post at the Wilson Center, she brought her sense that toxic partisanship prevents Congress from addressing the biggest questions facing the nation in a productive and nonpartisan manner. Under her leadership, the Wilson Center has begun the “National Conversation” series to tackle the toughest issues.

The recently held inaugural event showed great promise. Two active military officers, Captain Wayne Porter (USN) and Colonel Mark Mykleby (USMC), writing under the pseudonym, “Mr. Y,” provided the framework for the discussion. Their vision for a new U.S. security story was presented in a white paper titled, “A National Strategic Narrative.” Their stated purpose is to provide a framework through which to view policy decisions well into the 21st century.

The encounter was lively and challenging, sometimes provocative, but always civil. I can summarize the immediate outcome by reporting a consensus that a narrative is missing and needed. It was a good start, but the discussion needs to continue until we reach a national consensus and not just one among five panelists and a moderator. I will not go into great detail in recapping the arguments and ideas presented, but will instead offer a contribution from each participant to whet your appetite.

Anne-Marie Slaughter, Princeton professor and former Director of Policy Planning for the U.S. Department of State began the session with a summary of the white paper, describing the changing nature of power and influence:We were never able to control international events but we had a much better possibility during the Cold War when you essentially had a bipolar world with two principal actors than we do in a world of countless state and non-state actors. Nobody controls anything in the 21st century, indeed it’s just not a very good century to be – it’s not a good time to be a control freak. [Laughter] Whether it’s your e-mail or global events it’s sort of the same problems. What you can do is influence outcomes. So we have to start by saying it’s an open system; you can’t control it but you can build up your credible influence.

Brent Scowcroft, National Security Advisor to two U.S. presidents, provided an historical framework for the discussion:I think we’re facing a historical discontinuity. The Treaty of Westphalia recognized the existence of the nation-state system codified it and so on. That was a replacement for the feudal system where our sovereignty was vague, divided between kings and princes and landowners and religious leaders. It created a new system and I think the epitome of the nation-state system was the 20th century. I think that globalization writ large is changing that system and globalization is eroding national borders. The financial crisis of 2008 showed us we’ve got a global economic system, what happened in one country spread immediately around. It also showed we don’t have a global way to deal with a global economic situation. Now, this force of globalization to me the best way to look at it is akin to the force of industrialization 250 years ago. Industrialization really created the modern nation state with a lot more power over its citizens to deal with issues than the earlier Westphalia state system had. And it brought the state together. It made it more powerful. Globalization is reacting the same way but in the opposite direction. It is diluting the power of the nation state to deal with the important things.

Thomas Friedman, Pulitzer-prize winning columnist for The New York Times, described the difference between virtual and real action:Exxon Mobil, they’re not on Facebook, they’re just in your face. [Laughter] Peabody Coal, they don’t have a chatroom. They’re in the cloakroom of the U.S. Congress with bags of money. So if you want to change the world, you gotta get out of Facebook and into somebody’s face whether that’s in the U.S. Congress or Tahrir Square. You’ll say, why I blogged on it. I blogged on it, really? That’s like firing a mortar into the Milky Way Galaxy, okay. [Laughter] There is a faux sense of activism out there that is really dangerous. The world, your world, may be digital but politics is still analog and we’ve kind of gotten away from that. Egypt changed. Yes, Facebook was hugely important in organizing people, but the fundamental change happened because a million people showed up in Tahrir Square.

Steve Clemons, founder of the American Strategy Program at the New America Foundation, added this thought on the essence of globalization:What globalization really is, is the disruption of cartels. What blogging is, individual blogging is saying is, I’m not gonna wait for The New York Times editor to tell me no any more or [laughter] to say yes three weeks from now. You know, it is the disruption of cartels and that is happening in every sector of society.

Robert Kagan, senior fellow with The Brookings Institution and a former State Department Policy Planning Officer, cautioned against rushing to utopian conclusions about the impact of our new levels of interconnectedness:Let me just give you an example of how even something new doesn’t necessarily change things the way we want them to or the way we expect them to. I’m positive by the way that human nature is not new. So you’re kind of dealing with the same beast, and I use the term advisably, as you’ve been dealing with for millennia. Let’s talk about the fact that everyone can communicate with each other on the internet. You know, when people communicate with each other especially across national boundaries sometimes it makes them grow closer. Sometimes it makes them hate each other more. If you read the Internet in China now it’s hyper nationalistic. Now, you can argue that because that’s where the government channel said and because they don’t let anybody else or anything else or you could say the Internet is a great vehicle for the Chinese people to express their hatred of the Japanese people. It certainly is doing that now. So does that mean the Internet is going to bring nations closer and solve problems? Not necessarily.

Representative Keith Ellison (D-MN), talked about the expectations of youth and how demographics will be a key consideration when defining a narrative:The Middle East is on my mind a lot these days, what it means if you have all these societies where 50 percent of the population is under 18 years old? You know this is – this has big implications. I mean, this is a demographic reality that is going to have vast implications for the United States. So one thing is it’s not going away because lots of these people who are 18 years old, their cohort just moves through. You know, they’re going to be there a long time and they have demands, they’re going to have needs, they’re going to have expectations. You mentioned justice. They expect us to act justly. And I, when people talk about anti-Americanism, for me part of what’s going on is unmet expectations not just ‘we don’t like it.’

For this abbreviated summary of the discussion, I give the final cautionary word to Steve Clemons, who had this to say in response to an audience question about how to begin the process of constructing a new narrative:This is a town of risk-averse institutions, a town of inertia, a town of vested interests. It’s not a town that really embraces the notion of how do you pivot very quickly and rapidly in a different direction. So, fundamentally you need to begin putting out narratives like this.

A transcript and video of the event is available from the Wilson Center and additional coverage can also be found right here on The New Security Beat.

John Milewski is the host of Dialogue Radio and Television at the Woodrow Wilson Center and can also be followed on The Huffington Post or Twitter.

Photo Credit: Adapted from “1989 – Berlin, Germany,” courtesy of flickr user MojoBaer.