Showing posts from category *Main.

-

Emily Puckart, MHTF Blog

Maternal Health Challenges in Kenya: An Overview of the Meetings

›The original version of this article, by Emily Puckart, appeared on the Maternal Health Task Force blog.

I attended the two day Nairobi meeting on “Maternal Health Challenges in Kenya: What New Research Evidence Shows” organized by the Woodrow Wilson International Center and the African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC). [Video Below]

First, here in Nairobi, participants heard three presentations highlighting challenges in maternal health in Kenya. The first presentation by Lawrence Ikamari focused on the unique challenges faced by women in rural Kenya. Presently Kenya is still primarily a rural country where childbearing starts early and women have high fertility rates. A majority of rural births take place outside of health institutions, and overall rural women have less access to skilled birth attendants, medications, and medical facilities that can help save their lives and the lives of their babies in case of emergency.

Catherine Kyobutungi highlighted the challenges of urban Kenyan women, many of whom deliver at home. When APHRC conducted research in this area, nearly 68 percent of surveyed women said it was not necessary to go to health facility. Poor road infrastructure and insecurity often prevented women from delivering in a facility. Women who went into labor at night often felt it is unsafe to leave their homes for a facility and risked their lives giving birth at home away from the support of skilled medical personnel and health facilities. As the urban population increases in the coming years, governments will need to expend more attention on the unique challenges women face in urban settings.

Finally, Margaret Meme explored a human rights based approach to maternal health and called on policymakers, advocates, and donors to respect women’s right to live through pregnancies. Further, she urged increased attention on the role of men in maternal health by increasing the education and awareness of men in the area of sexual and reproductive health as well as maternal health.

After these initial presentations, participants broke out into lively breakout groups to discuss these maternal health challenges in Kenya in detail. They reconvened in the afternoon in Nairobi to conduct a live video conference with a morning Washington, DC audience at the Woodrow Wilson Center. It was exciting to be involved in this format, watching as participants in Washington were able to ask questions live of the men and women involved in maternal health advocacy, research and programming directly on the ground in Kenya. It was clear the excitement existed on both sides of the Atlantic as participants in Nairobi were able to directly project their concerns and hopes for the future of maternal health in Kenya across the ocean through the use of video conferencing technology.

There was a lot of excitement and energy in the room in Nairobi, and I think I sensed the same excitement through the television screen in DC. I hope that this type of simultaneous dialogue, across many time zones, directly linking maternal health advocates around the globe, is an example of what will become commonplace in the future of the maternal health field.

Emily Puckart is a senior program assistant at the Maternal Health Task Force (MHTF).

Photo Credit: MHTF. -

Edward Carr, Open the Echo Chamber

Drought Does Not Equal Famine

›July 27, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Edward Carr, appeared on Open the Echo Chamber.

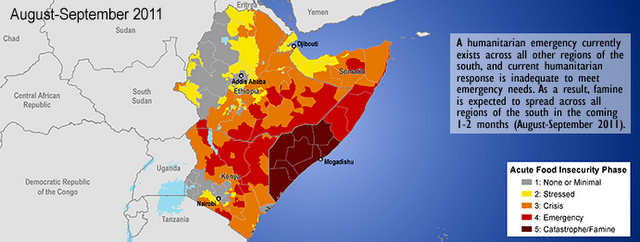

After reading a lot of news and blog posts on the situation in the Horn of Africa, I feel the need to make something clear: The drought in the Horn of Africa is not the cause of the famine we are seeing take shape in southern Somalia. We are being pounded by a narrative of this famine that more or less points to the failure of seasonal rains as its cause…which I see as a horrible abdication of responsibility for the human causes of this tragedy.

First, I recommend that anyone interested in this situation – or indeed in food security and famine more generally, to read Mike Davis’ book Late Victorian Holocausts. It is a very readable account of massive famines in the Victorian era that lays out the necessary intersection of weather, markets, and politics to create tragedy – and also makes clear the point that rainfall alone is poorly correlated to famine. For those who want a deeper dive, have a look at the lit review (pages 15-18) of my article “Postmodern Conceptualizations, Modernist Applications: Rethinking the Role of Society in Food Security” to get a sense of where we are in contemporary thinking on food security. The long and short of it is that food insecurity is rarely about absolute supplies of food – mostly it is about access and entitlements to existing food supplies. The Horn of Africa situation does actually invoke outright scarcity, but that scarcity can be traced not just to weather – it is also about access to local and regional markets (weak at best) and politics/the state (Somalia lacks a sovereign state, and the patchy, ad hoc governance provided by Al Shabaab does little to ensure either access or entitlement to food and livelihoods for the population).

For those who doubt this, look at the Famine Early Warning System Network (FEWS NET) maps I put in previous posts here and here (Editor: also above). Famine stops at the Somali border. I assure you this is not a political manipulation of the data – it is the data we have. Basically, the people without a functional state and collapsing markets are being hit much harder than their counterparts in Ethiopia and Kenya, even though everyone is affected by the same bad rains, and the livelihoods of those in Somalia are not all that different than those across the borders in Ethiopia and Kenya. Rainfall is not the controlling variable for this differential outcome, because rainfall is not really variable across these borders where Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia meet.

Continue reading on Open the Echo Chamber.

Image Credit: FEWS NET and Edward Carr. -

Farahnaz Zahidi Moazzam on the Population Reference Bureau’s “Women’s Edition” Trip to Ethiopia

›The original version of this article, by Farahnaz Zahidi Moazzam, appeared on the Population Reference Bureau’s Behind the Numbers blog.

My name is Farahnaz Zahidi Moazzam, and I’m a freelance journalist, writer, and editor from Pakistan. My passion is writing about human rights with a special focus on gender issues and reproductive health. Blogging is a personal joy to me, as I put my heart into my writing and blogging allows for a more personalized style. Digital journalism is a sign of evolution – one I happily accept. My pet peeve is marginalization on any grounds. I am a mother of a teenage daughter and live in Karachi.

As part of the Population Reference Bureau’s (PRB) group of journalists in Women’s Edition 2010-2012, I recently had the chance to travel to Ethiopia on a visit that was unforgettable. The visit inspired a series of seven brief travel-blogs, based on my seven days there. Women’s Edition is a wonderful opportunity to connect with other like-minded female journalists from developing countries around the world, and learn solutions to the problems from this interaction. The program has reaffirmed my belief that our commonalities are more than the differences.

Read Farahnaz Zahidi Moazzam’s posts from her trip to Ethiopia on her blog, Impassioned Ramblings, and view photos from the trip on PRB’s Facebook page.

Photo Credit: PRB. -

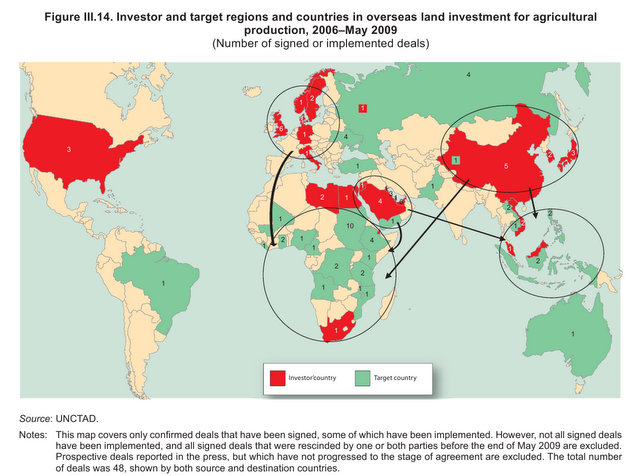

In Rush for Land, Is it All About Water?

›July 26, 2011 // By Christina DaggettOver the past few years, wealthy countries with shrinking stores of natural resources and relatively large populations (such as China, India, South Korea, and the Gulf states) have quietly purchased huge parcels of fertile farmland in Africa, South America, and South Asia to grow food for export to the parent country. With staple food prices shooting up and food security projected to worsen in the decades ahead, it is little wonder that countries are looking abroad to secure future resources. But the question arises: Are these “land grabs” really about the food — or, more accurately, are they “water grabs”?

The Great Water Grab

With growing urban populations, an expanding middle class, and increasingly scarce arable land resources, some governments and investors are snapping up the world’s farmland. Some observers, however, have pointed out that these dealmakers might be more interested in the water than the land.

In an article from The Economist in 2009, Peter Brabeck-Letmathe, the chairman of Nestlé, claimed that “the purchases weren’t about land, but water. For with the land comes the right to withdraw the water linked to it, in most countries essentially a freebie that increasingly could be the most valuable part of the deal.”

Consider some of the largest investors in foreign land: China has a history of severe droughts (and recently, increasingly poor water quality); the Gulf nations of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar, and Bahrain are among the world’s most water-stressed countries; and India’s groundwater stocks are rapidly depleting.

A recent report from the World Bank on global land deals highlighted the effect water scarcity is having on food production in China, South Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa, stating that “in contrast, Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America have large untapped water resources for agriculture.”

Keeping Engaged and Informed

“The water impacts of any investment in any land deal should be made explicit,” said Phil Woodhouse of the University of Manchester during the recent International Conference on Global Land Grabbing, as reported by the New Agriculturist. “Some kind of mechanism is needed to bring existing water users into an engagement on any deals done on water use.”

At the same conference, Shalmali Guttal of Focus on the Global South cautioned, “Those who are taking the land will also take the water resources, the forests, wetlands, all the wild indigenous plants and biodiversity. Many communities want investments but none of them sign up for losing their ecosystems.”

With demand for water expected to outstrip supply by 40 percent within the next 20 years, water as the primary motivation behind the rush for foreign farmland is a factor worth further exploration.

Global Farming

According to a report from the Oakland Institute, nearly 60 million hectares (ha) of African farmland – roughly the size of France – were purchased or leased in 2009. With these massive land deals come promises of jobs, technology, infrastructure, and increased tax revenue.

In 2008 South Korean industrial giant Daewoo Logistics negotiated one of the biggest African farmland deals with a 99-year lease on 1.3 million ha of farmland in Madagascar for palm oil and corn production. The deal amounted to nearly half of Madagascar’s arable land – an especially staggering figure given that nearly a third of Madagascar’s GDP comes from agriculture and more than 70 percent of its population lives below the poverty line. When details of the deal came to light, massive protests ensued and it was eventually scrapped after president Marc Ravalomanana was ousted from power in a 2009 coup.

While perhaps an extreme example, the Daewoo/Madagascar deal nonetheless demonstrates the conflict potential of these massive land deals, which are taking place in some of the poorest and hungriest countries in the world. In 2009, while Saudi Arabia was receiving its first shipment of rice grown on farmland it owned in Ethiopia, the World Food Program provided food aid to five million Ethiopians.

Other notable deals include China’s recent acquisition of 320,000 ha in Argentina for soybean and corn cultivation – a project which is expected to bring in $20 million in irrigation infrastructure, the Guardian reports – and a Saudi Arabian company which has plans to invest $2.5 billion and employ 10,000 people in Ethiopia by 2020, according to Gambella Star News.

But governments in search of cheap food aren’t the only ones interested in obtaining a piece of the world’s breadbasket: Individual investors are also heavily involved, and the Guardian reports that U.S. universities and European pension funds are buying and leasing land in Africa as well.

The Future of Land and Water

Whatever the benefits or pitfalls, large-scale land deals around the world look set to continue. The world is projected to have 7 billion mouths to feed by the end of this year and possibly 10 billion plus by the end of the century.

Currently, agriculture uses 11 percent of the world’s land surface and 70 percent of the world’s freshwater resources, according to UNESCO. If and when the going gets tough, how will the global agricultural system respond? Whose needs come first – the host countries’ or the investing nations’?

Christina Daggett is a program associate with the Population Institute and a former ECSP intern.

Photo Credit: Number of signed or implemented overseas land investment deals for agricultural production 2006-May 2009, courtesy of GRAIN and the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD).

Sources: BBC News, Canadian Water Network, Christian Science Monitor, Circle of Blue, The Economist, Gambella Star News, Guardian, Maplecroft, New Agriculturalist, Oakland Institute, State Department, Time, UNFPA, UNESCO, World Bank, World Food Program. -

Eddie Walsh, The Diplomat

Indonesia’s Military and Climate Change

›July 22, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Eddie Walsh, appeared on The Diplomat’s ASEAN Beat blog.

With more than 17,000 islands and 80,000 kilometers of coastline, Indonesia is extremely vulnerable to climate change. Analysts believe that rising temperatures will almost certainly have a negative impact on human security in Indonesia, which in turn will increase the probability of domestic instability and introduce new regional security concerns. With this in mind, it’s important that Indonesia’s armed forces take a range of measures to prioritize environmental security, including procuring new equipment, strengthening bilateral and multilateral relations, and undertaking training for new roles and missions.

Indonesians are expected to experience warmer temperatures, increased precipitation (in the northern islands), decreased precipitation (in the southern islands), and changes in the seasonality of precipitation and the timing of monsoons. These phenomena could increase the risk of either droughts or flooding, depending on the location, and could also reduce biodiversity, lead to more frequent forest fires and other natural disasters, and increase diseases such as malaria and dengue, as well incidences of diarrhea.

The political, economic, and social impact of this will be significant for an archipelago-based country with decentralized governance, poor infrastructure, and a history of separatist and radical conflict. According to a World Bank report, the greatest concern for Indonesia will be decreased food security, with some estimates projecting variance in crop yields of between -22 percent and +28 percent by the end of the century. Rising sea levels also threaten key Indonesian cities, including Jakarta and Surabaya, which could stimulate ‘disruptive internal migration’ and result in serious economic losses. Unsurprisingly, the poor likely will be disproportionately impacted by all of this.

Continue reading on The Diplomat.

Sources: World Bank.

Photo Credit: “Post tsunami wreckage Banda Aceh, Sumatra, Indonesia,” courtesy of flickr user simminch. -

Water, Energy, and the U.S. Department of Defense

› Energy for the War Fighter is the U.S. Department of Defense’s first operational energy strategy, mandated by congress last year. Energy security for the department means having assured access to reliable supplies of energy and the ability to protect and deliver energy to meet operational (non-facilities-related) needs. The report is divided into three main parts, which address reducing current demand for energy in military operations; expanding and securing the supply of energy for military operations; and building consideration of energy security into future force decisions. The strategy is designed to both support current military operations and to focus future energy investments accordingly. Previous federal energy mandates exempted the military’s field operations, which account for three-quarters of the department’s energy consumption. The department as a whole makes up 80 percent of the federal government’s annual energy use.

Energy for the War Fighter is the U.S. Department of Defense’s first operational energy strategy, mandated by congress last year. Energy security for the department means having assured access to reliable supplies of energy and the ability to protect and deliver energy to meet operational (non-facilities-related) needs. The report is divided into three main parts, which address reducing current demand for energy in military operations; expanding and securing the supply of energy for military operations; and building consideration of energy security into future force decisions. The strategy is designed to both support current military operations and to focus future energy investments accordingly. Previous federal energy mandates exempted the military’s field operations, which account for three-quarters of the department’s energy consumption. The department as a whole makes up 80 percent of the federal government’s annual energy use. The Water Energy Nexus: Adding Water to the Energy Agenda, by Diana Glassman, Michele Wucker, Tanushree Isaacman, and Corinne Champilouis of the World Policy Institute, attempts to show the correlation between energy and water to motivate policy makers to consider the implications of their dual consumption. “Nations around the world are evaluating their energy options and developing policies that apply appropriate financial carrots and sticks to various technologies to encourage sustainable energy production, including cost, carbon, and security considerations,” write the authors. “Water needs to be a part of this debate, particularly how communities will manage the trade-offs between water and energy at the local, national, and cross-border levels.” The study provides the context needed to evaluate key tradeoffs between water and energy by providing “the most credible available data about water consumption per unit of energy produced across a wide spectrum of traditional energy technologies,” they write.

The Water Energy Nexus: Adding Water to the Energy Agenda, by Diana Glassman, Michele Wucker, Tanushree Isaacman, and Corinne Champilouis of the World Policy Institute, attempts to show the correlation between energy and water to motivate policy makers to consider the implications of their dual consumption. “Nations around the world are evaluating their energy options and developing policies that apply appropriate financial carrots and sticks to various technologies to encourage sustainable energy production, including cost, carbon, and security considerations,” write the authors. “Water needs to be a part of this debate, particularly how communities will manage the trade-offs between water and energy at the local, national, and cross-border levels.” The study provides the context needed to evaluate key tradeoffs between water and energy by providing “the most credible available data about water consumption per unit of energy produced across a wide spectrum of traditional energy technologies,” they write.

Sources: U.S. Department of Defense. -

UN Security Council Debates Climate Change

› Today the UN Security Council is debating climate change and its links to peace and international security. In this short video, ECSP Director Geoff Dabelko outlines his hopes for today’s session and its follow-on activities. He suggests it is time to move from problem identification to problem solving by developing practical steps to respond to climate-security links.

Today the UN Security Council is debating climate change and its links to peace and international security. In this short video, ECSP Director Geoff Dabelko outlines his hopes for today’s session and its follow-on activities. He suggests it is time to move from problem identification to problem solving by developing practical steps to respond to climate-security links.

This Security Council debate was held at the instigation of the German government, chair of the Security Council this month. But it is not the first time this body has debated climate and security. In 2007, the United Kingdom used its prerogative as chair to introduce the topic in the security forum. Opinions from member states diverged on whether the Security Council was the appropriate venue for climate change.

Largely at the instigation of the Alliance of Small Island States, the UN General Assembly tackled climate and security links in 2009. The resulting resolution also spurred the UN Secretary-General to produce a summary report on the range of climate and security links.

Sources: Reuters, UN. -

Failed States Index 2011

›“The reasons for state weakness and failure are complex, but not unpredictable,” said J.J. Messner, one of the founders of the Fund for Peace’s Failed States Index, at the launch of the 2011 version of report in Washington last month. The Index is an analytical tool that could aid policymakers and governments seeking to prevent and mitigate state collapse by identifying patterns of underlying drivers of state instability.

The Index ranks 177 countries according to 12 primary social, economic, and political indicators based on analysis of “thousands of news and information sources and millions of documents” and distilled into a form that is meant to be “relevant as well as easily digestible and informative,” according to the creators. “By highlighting pertinent issues in weak and failing states,” they write, the Index “makes political risk assessment and early warning of conflict accessible to policymakers and the public at large.”

Common Threats: Demographic and Natural Resource Pressures

The Index reveals that half of the 10-most fragile states are acutely demographically challenged. The composite “Demographic Pressures” category takes into account population density, growth, and distribution; land and resource competition; water scarcity; food security; the impact of natural disasters; and public health prevention and control. Additional population indices are found in “Massive Movement of Refugees or Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs),” and health indicators, including infant mortality, water, and sanitation, are spread across several categories.

Not surprisingly, some of the most conflict-ridden countries show up at the top of the list. The Index highlights some of the lesser known issues that contribute to their misery: demographic and natural resource stresses in Afghanistan, Iraq, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Yemen (a list that would include Palestine, if inclusion in the Index were not contingent on UN membership); the DRC’s conflict minerals; and Somalia and Sudan’s myriad of environmental and migration problems, which play major roles in their continued instability.

Haiti, with its poor health and lack of infrastructure and disaster resilience, was deemed the Index’s “most-worsened” state of 2011. The January 2010 earthquake and its ensuing “chaos and humanitarian catastrophe” demonstrated that a single event can trigger the collapse of virtually every other sector of society, causing what Messner termed the “Humpty Dumpty effect” – while a state can deteriorate quickly, it is much harder to put it back together again.

The inclusion of natural resource governance within the social and economic indicators would render the Index a more complete analytical tool. In a 2009 report, the UN Environment Program (UNEP) found that “since 1990, at least eighteen violent conflicts have been fueled by the exploitation of natural resources,” and that effective natural resource management is a necessary component of conflict prevention and peacebuilding operations.

The Elephant in the Room: Predicting the Arab Spring

Why did the Index fail to predict the Arab Spring sweeping the Middle East and North Africa? Many critics assert that the inconsistent ranking of the states, ranging from Yemen (ranked 13th) to Bahrain (ranked 129th), demonstrates that the Index is a poor indicator of state instability. Particularly, critics argue that many of the countries experiencing revolutions were ranked artificially low.

“Of course, the Failed States Index did not predict the Arab Spring, and nor is it intended to predict such upheavals,” said Messner at the launch event. “But by digging down deeper into the specific indicator analysis, it was possible to observe the growing tensions in those countries.” The Index has consistently highlighted specific troubling indicators for the region, such as severe demographic pressures, migration, group grievance, human rights, state legitimacy, and political elitism.

Blake Hounshell, a correspondent with Foreign Policy (long-time collaborators with the Fund for Peace on the Index), wrote that the Index was never meant to be a “crystal ball” – even the best statistical data cannot truly encapsulate the complex realities that lead to inherently unpredictable events, such as revolutions. “It’s thousands of individual decisions, not rows of statistics, that add up to political upheaval,” Hounshell continued.

Demographer Richard Cincotta’s work on Tunisia’s revolution illuminates how the Index’s linear indicators can mask a complex reality. Whereas the Failed States Index simply measures “demographic pressure” as a linear function of how youthful a population is, Cincotta pointed out at a Wilson Center event that it was actually Tunisia’s relative demographic maturity that paved the way for its revolution and gives it a good chance of achieving a liberal democracy. Other countries in the region are much younger than Tunisia (Yemen being the youngest). The Arab Spring demonstrates that static indicators alone often do not have the capacity to predict complex social and political revolutions.

Sources: Foreign Policy, The Fund for Peace, UNEP.

Image Credit: Failed States Index 2011, Foreign Policy.