-

Migration and Environmental Change, Minority Land Rights and Livelihoods

›Migration and Global Environmental Change: Future Challenges and Opportunities, from the UK Government Office for Science’s Foresight Programme, looks at how environmental change, including climate change, land degradation, and the degradation of coastal and marine ecosystems, over the next 50 years will affect migration trends. The report emphasizes that migration is a complex and multi-causal phenomenon, which makes it difficult to differentiate environmental migrants as a distinct group. Nevertheless, research suggests that global environmental changes will affect the drivers of migration, particularly economic forces, such as rural wages and agricultural productivity.

Though Foresight finds that many will use migration as an adaptation strategy that improves resilience to environmental change, they also point out that some affected individuals may become “trapped” in vulnerable situations, lacking the financial capacity to respond to environmental changes, while others may be able to move but will inadvertently enter more exposed areas, particularly, at risk urban centers. For recommendations, they stress the importance of strategic, long-term urban planning, and recognition within adaptation and development policies that migration can be part of the solution.

A study, released on December 5 by Minority Rights Group International, finds that minority communities in Kenya, Uganda, and South Sudan face significant challenges around access to and control of critical natural resources. The report, Land, Livelihoods, and Identities: Inter-Community Conflicts in East Africa, shows how rapid population growth, climate change, and globalization are increasing competition for land, water, and forest and mineral resources in territories traditionally occupied by minority groups. These pressures can undermine livelihoods and trigger multiple and overlapping conflicts, especially where ownership has not been formalized in law. The study also notes that women are doubly vulnerable as their access to land and resources is frequently mediated through customary law, which depends on their communities retaining control over traditional territory. Although the report makes national-level legal and policy recommendations, the authors note that some of the most effective resource management and conflict resolution strategies adapt traditional cultural practices to the current circumstances of communities. -

Can “Climate-Smart Agriculture” Help Feed Africa’s Growing Population?

›December 13, 2011 // By Brenda ZuluFood production needs to increase 70 percent by 2050 to meet the demands of a growing world population, said former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan in a keynote address on “climate-smart agriculture” at a COP-17 event hosted by the World Bank and African Union. Annan, who is now chairman of the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), said this was a particular concern in Africa, where four out of five citizens are dependent on agriculture for their livelihoods.

One in seven people in the world do not have enough food to eat, Annan said, and climate change is expected to make this challenge more difficult to overcome. Climate-smart agriculture includes a wide variety of techniques that help increase the resilience of communities and protect them from extreme weather events, such as terracing to prevent soil erosion, improving weather forecasting, managing water runoff, and developing irrigation systems.

“Climate change affects us by undermining our resource base through water and soil degradation,” said Prime Minister of Ethiopia Meles Zenawi at the event. “There is need to protect the resources and to rehabilitate green areas of our land.” He said that since 70 percent of Africans are small-scale farmers and that most of the poor in Africa were farmers, there is no better way to fight poverty on the continent than through agriculture.

South African President Jacob Zuma said at the event that given that the UN projects a population of more than nine billion people in the world by 2050, agriculture should be a priority as it is more vulnerable to climate change than any other sector.

“Climate-smart agriculture includes proven practical techniques such as mulching, intercropping, conservation agriculture, integrated crop management and agro forestry, improved grazing, and innovative better weather management,” he said, all of which have the potential to help increase crop yields.

Mary Robinson, chair of the Global Leaders Council for Reproductive Health, said there could be no smart agriculture without integrating women’s issues, because climate change affects women disproportionately. “Women make the connection between climate-smart agriculture, food security, and gender,” she said.

“Our ability to feed the growing population under climate variability and change will require new expertise and harmonized efforts,” said Robinson.

Annan agreed, saying African women should be fully involved in early action that can support technical assistance, such as screening agriculture plans to ensure they are “climate smart” as well as integrating climate resilience and mitigation into ongoing poverty-reduction programs and testing new approaches.

But according to Brylyne Chitsunge, a farmer from Pretoria speaking on the panel, things will need to change considerably from the status quo. “The small-scale farmer remains very much marginalized in institutions,” she said. “They exist on paper but they really don’t exist.”

Brenda Zulu is a member of Women’s Edition for Population Reference Bureau and a freelance writer based in Zambia. Her reporting from the COP-17 meeting in Durban (see the “From Durban” series on New Security Beat) is part of a joint effort by the Aspen Institute, Population Action International, and the Wilson Center.

Sources: World Bank, World Food Programme.

Photo Credit: “Cultivated hillsides,” courtesy of flickr user coda (Damien du Toit). -

Book Preview: In ‘War and Conflict in Africa’, GWU Scholar Skeptical That Natural Resources Play a Leading Role

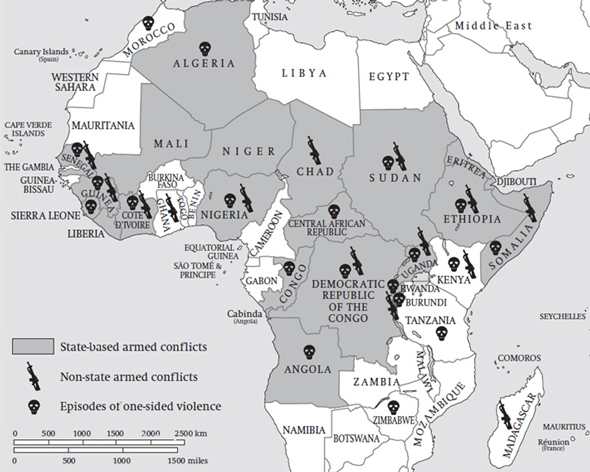

›November 30, 2011 // By Elizabeth Leahy MadsenWhile there is widespread agreement that the incidence of conflict in Africa is high, scholars and development agencies alike debate its driving forces and how to move toward solutions. Paul Williams, associate professor in the Elliott School of International Affairs at George Washington University and collaborator with the Wilson Center’s Africa Program, recently published a book that aims to both quantify African conflicts and devise a framework of their causes. In War and Conflict in Africa, Williams evaluates which factors explain the frequency of conflict in Africa during the post-Cold War era and how the international community has tried to build peace and prevent future conflict.

Although there have been promising trends toward establishing peace and democracy in some African countries, the continent still accounts for about one-third of all armed conflicts annually – more than Europe, the Middle East, and the Americas combined. International responses to these events range from focused humanitarian and conflict resolution efforts, to new regional organizations and global strategic and defense partnerships.

Seven of the 16 current UN peacekeeping missions operate in Africa, more than any other continent. The UK government has elected to spend nearly one-third of its development assistance in conflict-affected areas, and more than half of its “focus” countries are in Africa. In 2008, the Department of Defense created the U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM), whose commander, General Carter Ham, in a speech to Congress earlier this year, described “an insidious cycle of instability, conflict, environmental degradation, and disease that erodes confidence in national institutions and governing capacity,” as motivation for American military attention. “This in turn often creates the conditions for the emergence of a wide range of transnational security threats,” he said.

Evaluating the Ingredients of Conflict

Williams rejects earlier theses that attribute conflict across the continent to a single factor, such as the boundary legacies of colonialism, greed, or ethnicity. Instead, he characterizes African conflicts as “recipes” composed of case-specific mixes of factors, many of which are underlying and only some of which are sufficient triggers for conflict. “Collier is wrong,” Williams explained in an email interview. “Governance structures are always an important part of the buildup to war.”

Five “ingredients” of conflict are examined in-depth: neo-patrimonial governance structures; natural and human resources; sovereignty and self-determination; ethnicity; and religion. Among these, the book presents a fairly skeptical view of resources, ethnicity, and religion as immediate drivers of conflict. This assessment that environmental and identity issues are not sufficient to generate conflict on their own aligns with the book’s overarching argument: The decisions of political actors can instigate conflict or motivate peace from virtually any context, manipulating factors such as ethnicity and religion for their own advantage.

Effects of Natural Resources Are “Open-Ended”

A widely publicized thread of peace and conflict studies posits that resources, either when scarce or abundant, have an important role in triggering wars. A 2009 UN Environment Programme report found that 40 percent of all internal conflicts since 1950 “have a link to natural resources.” Recent peer-reviewed research has suggested that certain environmental changes increase the likelihood of civil conflicts or are directly responsible for it. Yet the question remains a source of much debate. For his part, Williams asserts that natural resources alone are insufficient to cause conflict.

War and Conflict in Africa presents several reasons that researchers and policymakers should avoid linking resources directly to conflict without considering the influence of intervening factors. Chief among them is that the value of any resource is socially constructed – no stone or river carries worth until humans decide so. Therefore, Williams argues that “it is political systems, not resources per se, that are the crucial factor in elevating the risk of armed conflict.”

The book suggests that two extant theories successfully demonstrate the connection between resources and conflict. The first body of research finds that conflict is more likely in regions that face a combination of resource abundance and a high degree of social deprivation. The second theory suggests that the link between resources and conflict lies in bad governance, whether exploitative or unstable. Both theories have explanatory power for Williams’s central line of thinking: Resources can be either a blessing or a curse, depending on leadership.

“Inserted into a context where corrupt autocrats have the advantage, resources will strengthen their hand and generate grievances,” he writes (p. 93). “Inserted into a stable democratic system, they will enhance the opportunities for leaders to promote national prosperity.”

Population and the Environment

Williams does accede that particular resource factors – land and demography, for example – may play a more significant role than others in conflict, but calls for more research. In a brief discussion of population age structure, the book suggests that there is no single relationship between demography and conflict but multiple ways that the two can relate. Williams mentions the theory that “large pools of disaffected youth” with few opportunities can raise the risk of volatility. However, he then notes other research showing that the most marginalized members of certain African societies are less likely to participate in political protests and more likely to tolerate authoritarian rule than those who are better off.

“The most marginalized from society are the truly destitute without patrons and suffering from severe poverty. They may well be inclined to join an insurgency movement once it begins to snowball but they will not usually play a key role in establishing the rebel group in the first place,” Williams said. However, “any time there are large pools of poor and unemployed youth there is the potential for leaders to manipulate them.”

On environmental resources, the book argues that land should be a central feature of quantitative research on the relationship between resources and conflict. Most African economies continue to rely on agriculture, and Williams observes that land has been “at the heart” of many conflicts in the region through a variety of governance-related mechanisms relating to its management and control. He places less emphasis on water scarcity as a potential factor in conflict, noting that the 145 water-related treaties signed around the world in the past decade auger well for cooperation rather than competition.

Williams is also dubious of emerging arguments that climate change could directly increase the incidence of conflict, either through changing weather patterns or climate-induced migration.

“Because armed conflicts are, by definition, the result of groups choosing to fight one another, any process, including climate change, can never be a sufficient condition for armed conflict to occur,” he argued. “Armed conflicts result from the conscious decisions of actors which might be informed by the weather but are never simply caused by it.”

No Simple Formula

Williams is not the only observer to find the narrative that resource shortage (or abundance) precipitates conflict too simplistic. His message to policymakers is a common refrain from academics and analysts seeking to counteract policymakers’ quest for simple formulas: We need more data.

“When deciding how to spend our money, we need to spend more of it on developing systems which deliver accurate knowledge about what is happening on the ground, often in very localized settings,” Williams said. War and Conflict in Africa contributes to a more complex understanding of the political actors and systems that catalyze or prevent conflict and offers a cautionary tale to those who seek only proven, easy predictions.

Elizabeth Leahy Madsen is a consultant on political demography for the Wilson Center’s Environmental Change and Security Program and senior technical advisor at Futures Group. She was previously a senior research associate at Population Action International. Full disclosure: She was a graduate student of Paul Williams’ in 2007.

Sources: DFID, Englebert and Ron (2004), Ham (2011), Hsiang et al (2011), Kahl (1998), Leysens (2006),Østby et al (2009), Radelet (2010), Themnér and Wallensteen (2011), UNEP (2009), UN Peacekeeping, Williams (2011)

Image Credit: Conflicts in Africa 2000-09, reprinted with permission courtesy of P.D. Williams, War and Conflict in Africa (Williams, 2011), p.3. -

Supply and Demand, Land and Power in the Global South

›In “Competition over Resources: Drivers of Insecurity and the Global South,” author Hannah Brock examines how an increased demand for non-renewable resources could lead to insecurity and contribute to local and international discord. The first of four papers examining what the Oxford Research Group has identified as the “most important underlying drivers of insecurity,” the paper focuses on competition over resources – specifically energy, water, and food – and argues that “a new way of approaching security is needed, one that addresses the drivers of conflict: ‘curing the disease’ rather than ‘fighting the symptoms.’” Through numerous examples, Brock illustrates the various strategies that nations are currently undertaking to satisfy demand and cautions that “where northern states and corporations buy access to southern resources, regulatory principles may be required to ensure this competition does not impair the human rights and security of local populations.”

A new briefing paper from Oxfam, “Land and Power: The growing scandal surrounding the new wave of investments in land,” heavily criticizes the rising trend of foreign land acquisitions, or “land grabs,” that have occurred since the 2007-08 food prices crisis, calling them an infringement on the rights of more vulnerable populations and decrying their environmental impact. The authors use case studies in Uganda, Indonesia, Guatemala, Honduras, and South Sudan to argue that land grabbing is a type of “development in reverse.” “National governments have a duty to protect the rights and interests of local communities and land rights-holders,” Oxfam writes, “but in the cases presented here, they have failed to do so.” The authors conclude with recommendations to improve transparency and shift power more towards local rights. -

In Colombia, Rural Communities Face Uphill Battle for Land Rights

›November 14, 2011 // By Kayly Ober“The only risk is wanting to stay,” beams a Colombian tourism ad, eager to forget decades of brutal internal conflict; however, the risk of violence remains for many rural communities, particularly as the traditional fight over drugs turns to other high-value goods: natural resource rights.

La Toma: Small Town, Big Threats

In the vacuum left by Colombia’s war on drugs, re-armed paramilitary groups remain a threat to many rural civilians. Organized groups hold footholds, particularly in the northeast and west, where they’ve traditionally hidden and exploited weak governance. Over the past five years, their presence has increased while their aims have changed.

A recent PBS documentary, The War We Are Living (watch below), profiles the struggles of two Afro-Colombian women, Francia Marquez and Clemencia Carabali, in the tiny town of La Toma confronting the paramilitary group Las Aguilas Negras, La Nueva Generacion. The Afro-Colombian communities the women represent – long persecuted for their mixed heritage – are traditional artisanal miners, but the Aguilas Negras claim that these communities impede economic growth by refusing to deal with multinationals interested in mining gold on a more industrial scale in their town.

For over seven years, the Aguilas Negras have sent frequent death threats and have indiscriminately killed residents, throwing their bodies over the main bridge in town. At the height of tensions in 2010, they murdered eight gold miners to incite fear. Community leaders know that violence and intimidation by the paramilitary group is part of their plan to scare and displace residents, but they refuse to give in: “The community of La Toma will have to be dragged out dead. Otherwise we’re not going to leave,” admits community leader Francia Marquez to PBS.

La Toma’s predicament is further complicated by corruption and general disinterest from Bogota. Laws that explicitly require the consent of Afro-Colombian communities to mine their land have not always been followed. In 2010, the Department of the Interior and the Institute of Geology and Minerals awarded a contract, without consultation, to Hector Sarria to extract gold around La Toma and ordered 1,300 families to leave their ancestral lands. Tension exploded between the local government and residents.

The community – spurred in part by Marquez and Carabali – geared into action; residents called community meetings, marched on the town, and set up road blocks. As a result, the eviction order was suspended multiple times, and in December 2010, La Toma officially won their case with Colombia’s Constitutional Court. Hector Sarria’s mining license as well as up to 30 other illegal mining permits were suspended permanently. But, as disillusioned residents are quick to point out, the decision could change at any time.

“Wayuu Gold”

Much like the people of La Toma, the indigenous Wayuu people who make their home in northeast Colombia have also found themselves the target of paramilitary wrath. Wayuu ancestral land is rich in coal and salt, and their main port, Bahia Portete, is ideally situated for drug trafficking, making them an enticing target. In 2004, armed men ravaged the village for nearly 12 hours, killing 12, accounting for 30 disappearances, and displacing thousands. Even now, seven years later, those brave enough to lobby for peace face threats.

Now, other natural resource pressures have emerged. In 2011, growing towns nearby started siphoning water from Wayuu lands, and climate change is expected to exacerbate the situation. A 2007 IPCC report wrote that “under severe dry conditions, inappropriate agricultural practices (deforestation, soil erosion, and excessive use of agrochemicals) will deteriorate surface and groundwater quantity and quality,” particularly in the Magdalena river basin where the Wayuu live. Glacial melt will also stress water supplies in other parts of Colombia. The threat is very real for indigenous peoples like the Wayuu, who call water “Wayuu gold.”

“Without water, we have no future,” says Griselda Polanco, a Wayuu woman, in a video produced by UN Women.

The basic right to water has always been a contentious issue for indigenous peoples in Latin America – perhaps most famously in Cochabomba, Bolivia – and Colombia is no different: most recently 10,000 protestors took to the streets in Bogota to lobby for the right to water.

Post-Conflict Land Tenure Tensions

Perhaps the Wayuu and people of La Toma’s best hope is in a new Victims’ Law, ratified in June 2011, but in the short term, tensions look set to increase as Colombia works to implement it. The law will offer financial compensation to victims or surviving close relatives. It also aims to restore the rights of millions of people forced off their land, including many Afro-Colombian and indigenous peoples.

But “some armed groups – which still occupy much of the stolen land – have already tried to undermine the process,” reports the BBC. “There are fears that they will respond violently to attempts by the rightful owners or the state to repossess the land.”

Rhodri Williams of TerraNullius, a blog that focuses on housing, land, and property rights in conflict, disaster, and displacement contexts, wrote in an email to New Security Beat that there are many hurdles in the way of the law being successful, including ecological changes that have already occurred:Perhaps the biggest obstacle is the fact that many usurped indigenous and Afro-Colombian territories have been fundamentally transformed through mono-culture cultivation. Previously mixed ecosystems are now palm oil deserts and no one seems to have a sense of how restitution could meaningfully proceed under these circumstances. Compensation or alternative land are the most readily feasible options, but this flies in the face of the particular bond that indigenous peoples typically have with their own homeland. Such bonds are not only economic, in the sense that indigenous livelihoods may be adapted to the particular ecosystem they inhabit, but also spiritual, with land forming a significant element of collective identity. Colombia has recognized these links in their constitution, which sets out special protections for indigenous and Afro-Colombian groups, but has failed to apply these rules in practice. For many groups, it may now be too late.

As National Geographic explorer Wade Davis said at the Wilson Center in April, climate change can represent as much a psychological and spiritual problem for indigenous people as a technical problem. Unfortunately, as land-use issues such as those faced by Afro-Columbian communities, the Wayuu, and many other indigenous groups around the world demonstrate, there is a legal dimension to be overcome as well.

Sources: BBC News, Colombia Reports, International Displacement Monitoring Centre, PBS, Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, UN Women. The War We Are Living, part of the PBS series Women, War, and Peace, was instrumental to the framing of this piece.

Image and Video Credit: “Countryside Near Manizales, Colombia,” courtesy of flickr user philipbouchard; The War We Are Living video, courtesy of PBS. -

Rwanda: Dramatic Uptake in Contraceptive Use Spurs Unprecedented Fertility Decline

›November 8, 2011 // By Elizabeth Leahy Madsen

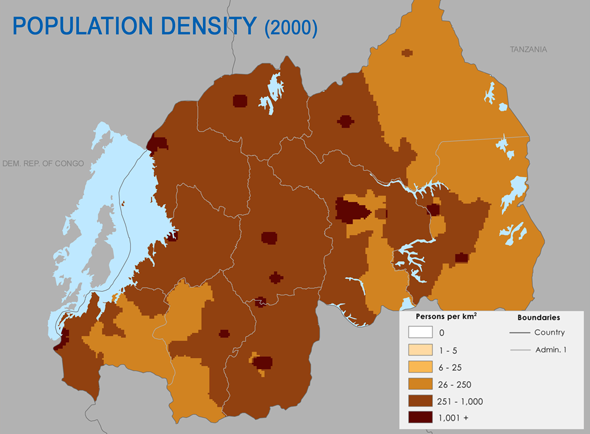

With over 400 people per square kilometer, the highest rate on the African mainland, population density is perhaps the most widely-discussed factor of Rwanda’s demography. Some scholars, notably Jared Diamond, have argued that it played a primary role in sparking the 1994 genocide through competition for land (although others present a more complex theory based in policies and governance).

-

Pascal Gakwaya Kalisa, PHE Champion

Coffee Farmer and Extension Manager Promotes Improved Health and Livelihoods in Rwandan Coffee Communities

›

This PHE Champion profile was produced by the BALANCED Project.

Mr. Pascal Gakwaya Kalisa has produced coffee in the densely populated country of Rwanda for the past nine years. A proud member of the 1,200 member Maraba Coffee Cooperative in Huye District in the Southern Province of Rwanda, Kalisa knows that a larger income alone does not ensure a better quality of life for his fellow coffee farmers and their families. He also knows that a successful coffee growing/exporting enterprise depends on preserving the fragile Rwandan soils, as well as on the health and well-being of farming families and communities. Therefore, Kalisa and other cooperative members treat the land and trees with a level of personal care that is necessary for optimum organic production and soil preservation.

Kalisa and the community have set up small, garden-sized coffee farms that are more productive than usual. Cooperative washing stations have enabled the small-scale farmers to improve product quality, and the cooperatives themselves are learning to negotiate better coffee prices with international buyers. Through such efforts and the support of many international donors and industry partners, Rwanda has become a producer of high quality specialty coffee since 2005, and its coffees are being marketed through renowned coffee roasters and importers in the United States, Europe, and Japan. In just six short years, Rwandan farmers have doubled their incomes and created 2,000 jobs, and the first renowned specialty coffee competition Cup of Excellence in Africa was held in Rwanda in 2008.

SPREAD: A Community Partnership

Recognizing the broad-based health, social, and economic needs of coffee farmers and their families in this part of East Africa, the U.S Agency for International Development initiated the Sustaining Partnerships to Enhance Rural Enterprise and Agribusiness Development project (SPREAD) to provide rural cooperatives and enterprises involved in high-value commodity chains with both appropriate technical assistance and access to health-related services and information. It is this combination of technical assistance and health-related outreach and services that has resulted in increased and sustained incomes and improved livelihoods.

Kalisa and other members of various cooperatives that SPREAD supports recognize that not only should farmers and their families preserve the land, but they must also preserve their own health in order to perform the labor needed to farm the crop that will produce the steady stream of high quality coffee upon which their livelihoods depend. Initiating community dialogues around issues such as protected sex, gender roles, and how coffee revenue is spent within households has also been crucial to project success among both youth and adults.

In his role as coffee zone coordinator for the SPREAD project, Kalisa works with coffee cooperatives to implement improved agricultural practices that improve the quality of their crop. This includes using cleaner environmental practices during coffee processing, such as introducing composting of coffee cherry pulp. Kalisa also helps disseminate integrated health and coffee messages through a weekly coffee talk-show produced by the National University of Rwanda’s Radio Salus, called Imbere Heza (“Bright Future”). In one show, for example, a man explained to a fellow farmer that to get good coffee cherries, he should thin his trees to renew his plantation.

Integrating Healthy Lives

Kalisa has also helped the SPREAD project’s health team deliver integrated messages on family planning, maternal and child health, alcohol, nutrition, gender issues, and the linkages between these. He uses examples such as the one about tree thinning to explain that families that space their children tend to be healthier, as they can plan the number of children to better fit with the financial and natural resources at hand.

Kalisa sees the benefits of using community agents to deliver integrated health, environment, and livelihood messages. This includes training extension agents to discuss environmental and human health issues in the context of coffee growing. Also, having coordinators from the coffee program and the health program go hand-in-hand to the field saves time, fuel, and other project costs. Kalisa believes that this campaign to educate coffee farmers and their families on the linkages between human health, a healthy environment, and strong livelihoods will lead to long-term change in their behavior, attitudes, and knowledge – change that will help them live better lives today and into the future.

This PHE Champion profile was produced by the BALANCED Project. A PDF version can be downloaded from the PHE Toolkit. PHE Champion profiles highlight people working on the ground to improve health and conservation in areas where biodiversity is critically endangered.

Photo Credit: “Rwanda photos 060,” courtesy of David Dewitt/counterculturecoffee. -

Robert Draper, National Geographic

People and Wildlife Compete in East Africa’s Albertine Rift

›The original version of this article, by Robert Draper, appeared on National Geographic.

The mwami remembers when he was a king of sorts. His judgment was sovereign, his power unassailable. Since 1954 he, like his father and grandfather before him, has been the head of the Bashali chiefdom in the Masisi District, an undulating pastoral region in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Though his name is Sylvestre Bashali Mokoto, the other chiefs address him as simply doyen – seniormost. For much of his adult life, the mwami received newcomers to his district. They brought him livestock or other gifts. He in turn parceled out land as he saw fit.

Today the chief sits on a dirty couch in a squalid hovel in Goma, a Congolese city several hours south of Masisi. His domain is now the epicenter of a humanitarian crisis that has lasted for more than a decade yet has largely eluded the world’s attention. Eastern Congo has been overtaken by thousands of Tutsi and Hutu and Hunde fighting over what they claim is their lawful property, by militias aiming to acquire land by force, by cattlemen searching for less cluttered pastures, by hordes of refugees from all over this fertile and dangerously overpopulated region of East Africa seeking somewhere, anywhere, to eke out a living. Some years ago a member of a rebel army seized the mwami’s 200-acre estate, forcing him, humiliated and fearing for his safety, to retreat to this shack in Goma.

The city is a hornet’s nest. As recently as two decades ago Goma’s population was perhaps 50,000. Now it is at least 20 times that number. Armed males in uniform stalk its raggedy, unlit streets with no one to answer to. Streaming out of the outlying forests and into the city market is a 24/7 procession of people ferrying immense sacks of charcoal on bicycles or wooden, scooter-like chukudus. North of the city limits seethes Nyiragongo volcano, which last erupted in 2002, when its lava roared through town and wiped out Goma’s commercial district. At the city’s southern edge lies the silver cauldron of Lake Kivu – so choked with carbon dioxide and methane that some scientists predict a gas eruption in the lake could one day kill everyone in and around Goma.

The mwami, like so many far less privileged people, has run out of options. His stare is one of regal aloofness. Yet despite his cuff links and trimmed gray beard, he is not a chief here in Goma. He is only Sylvestre Mokoto, a man swept into the hornet’s nest, with no land left for him to parcel out. As his guest, a journalist from the West, I have brought no gifts, only demeaning questions. “Yes, of course my power has been affected greatly,” the mwami snaps at me. “When others back up their claims with guns, there is nothing I can do.”

Continue reading on National Geographic.

Photo Credit: “Aerial View of Goma,” courtesy of UN Photo/Marie Frechon.

Showing posts from category land.