Showing posts from category foreign policy.

-

Is the Glass Half Full or Half Empty?

›The much-anticipated Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review(QDDR) demands to be taken seriously. Its hefty 250 pages present a major rethink of both American development policy and American diplomacy. Much of it is to be commended:

-

How Population Growth Is Straining the World’s Most Vital Resource

Turning Up the Water Pressure [Part Two]

›January 19, 2011 // By Russell SticklorThis article by Russell Sticklor appeared originally in the Fall 2010 issue of the Izaak Walton League’s Outdoor America magazine. Read part one here.

As concerns over water resources have grown around the globe, so too have proposed solutions, which range from common sense to absurd. Towing icebergs into the Persian Gulf or floating giant bags of fresh water across oceans to water-scarce countries are among the non-starters. But more moderate versions of those ideas are already being put into practice. These solutions showcase the power of human ingenuity — and reveal just how desperate some nations have become to secure water.

For example, India is doing business with a company out of tiny Sitka, Alaska, laying the framework for a water-export deal that could see huge volumes of water shipped via supertankers from the water-rich state of Alaska to a depot south of Mumbai. Depending on the success of this arrangement, moving bulk water via ship could theoretically become as commonplace as transoceanic oil shipments are today.

There is far greater potential, however, in harnessing the water supply of the world’s oceans. Perhaps more than any other technological breakthrough, desalination offers the best chance to ease our population-driven water crunch, because it can bolster supply. Although current desalination technology is not perfect, Eric Hoke, an associate professor of environmental engineering at the University of California-Los Angeles, told me via email, it is already capable of converting practically any water source into water that is acceptable for use in households, agriculture, or industrial production. Distances between supply and demand would be relatively short, considering that 40 percent of the world’s population — some 2.7 billion people — live within 60 miles of a coastline.

The Lure of Desalination

Although desalination plants are already up and running from Florida to Australia, the jury is still out on the role desalination can play in mitigating the world’s fresh water crisis. Concerns persist over the environmental impact seawater-intake pipes have on marine life and delicate coastal ecosystems. Another question is cost: Desalination plants consume enormous amounts of electricity, which makes them prohibitively expensive in most parts of the world. Desalination technology may not be able to produce water in sufficient scale — or cheaply enough — to accommodate the growing need for agricultural water. “Desalination is more and more effective [in producing] large quantities of water,” notes Laval University Professor Frédéric Lasserre in an interview. “But the capital needed is huge, and the water cost, now about 75 cents per cubic meter, is far too expensive for agriculture.” Although desalination might be “a good solution for cities and industries that can afford such water,” Lasserre predicts it “will never be a solution for agricultural uses.”

Nevertheless, desalination’s promise of easing future water crunches in populous coastal regions gives the technology game-changing potential at the global level. “Desalination technology,” Columbia University’s Upmanu Lall told said in an email, “will improve to the point that [water scarcity] will not be an issue for coastal areas.”

A Glass Half Full

With world population projected to grow by at least 2 billion during the next 40 years, water will likely remain a chief source of global anxiety deep into the 21st century. Because water plays such a fundamental role in everyday life across every society on earth, its shared stewardship may become an absolute necessity.

Take India and Pakistan’s landmark Indus Waters Treaty of 1960, which is still in effect today. The agreement — signed by two countries that otherwise can’t stand each other — shows that when crafted appropriately and with enough patience, international water-sharing pacts can help defuse tensions over water access before those tensions escalate into violence. Similar collaboration on managing shared waters in other areas of the world — a process that can be a bit bumpy at times — has proven successful to date.

Meanwhile, more widespread distribution of reliable family planning tools and services across Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa, and Asia will also be needed if the international community hopes to meaningfully address water scarcity concerns. Better access to healthcare and family planning tools would empower women to take greater control over their reproductive health and potentially elevate living standards in crowded parts of the developing world. Smaller family sizes would help decelerate population growth over time, easing the burden on water and soil resources in many areas. The key is ensuring such efforts have adequate funding. The United States recently pledged $63 billion over the next six years through its Global Health Initiative to help partner countries improve health outcomes through strengthened health systems, with a particular focus on improving the health of women and children.

Putting a dent in the global population growth rate will be important, but it must be accompanied by a sustained push for conservation — nowhere more so than in agriculture. Investing in the repair of a leaky irrigation infrastructure could help save water that might otherwise literally slip through the cracks. Attention to maintaining healthy soil quality — by practicing regular crop rotation, for example — could also help boost the efficiency of irrigation water.

Setting a Fair Price

The most enduring changes to current water-use practices may have to come in the form of pricing. In most parts of the world, including parts of the United States, groundwater removal is conducted with virtually zero oversight, allowing farmers to withdraw water as if sitting atop a bottomless resource. But as groundwater tables approach exhaustion, the equation changes; as Ben Franklin famously pointed out, “when the well’s dry, we know the worth of water.”

The key, then, is to establish the worth of water before this comes to pass. Smart pricing could encourage conservation by making it less economical to grow water-intensive crops, particularly those ill-suited to a particular climate. “Some crops being grown should not be grown . . . once the true cost of water is factored in,” Nirvikar Singh, a University of California-Santa Cruz economics professor who focuses on water issues, told me via email. Pricing would also provide a revenue stream for modernizing irrigation infrastructures and maintaining sewage systems and water treatment centers, further bolstering water efficiency and quality both in the United States and around the globe.

To be sure, implementing a pricing scheme for water resources — which have been essentially free throughout history — will be unpopular in many parts of the world. It’s natural to expect some pushback from the public as water managers and governments take steps to address the 21st century water crunch. But given the resource’s undeniable and universal value on an ever-more crowded planet, few options exist aside from using the power of the purse to push for more efficient water use.

In the end, however, water pricing must be combined with greater public value on water conservation — we must not flush water down our drains before using it to its full potential. Whether that involves improving the water transportation infrastructure, recycling wastewater, taking shorter showers, or turning to less water-intensive plants and crops, steps big and small need to be taken to better conserve and more equitably divide the world’s water to irrigate our farms, grow our economies, and sustain future generations.

Sources: Columbia Water Center, National Geographic, Population Reference Bureau, White House.

Photo Credits: “Juhu Beach Crowded,” courtesy of flickr user la_imagen, and “Irrigation (China),” courtesy of flickr user spavaai. -

How Population Growth Is Straining the World’s Most Vital Resource

Turning Up the Water Pressure [Part One]

›January 18, 2011 // By Russell SticklorThis article by Russell Sticklor appeared originally in the Fall 2010 issue of the Izaak Walton League’s Outdoor America magazine.

For many Americans, India — home to more than 1.1 billion people — seems like a world away. Its staggering population growth in recent years might earn an occasional newspaper headline, but otherwise, the massive demographic shift taking place on our planet is out of sight, out of mind. Yet within 20 years, India is expected to eclipse China as the world’s most populous nation; by mid-century, it may be home to 1.6 billion people.

So what?

In a world that is increasingly connected by the forces of cultural, economic, and environmental globalization, the future of the United States is intertwined with that of India. Much of this shared fate stems from global resource scarcity. New population-driven demands for food and energy production will increase pressure on the world’s power-generating and agricultural capabilities. But for a crowded India, domestic scarcity of one key resource could destabilize the country in the decades to come: clean, fresh water.

Stepping Into a Water-Stressed Future

From Africa’s Nile Basin and the deserts of the Middle East to the arid reaches of northern China, water resources are being burdened as never before in human history. There may be more or less the same amount of water held in the earth’s atmosphere, oceans, surface waters, soils, and ice caps as there was 50 — or even 50 million — years ago, but demand on that finite supply is soaring.

Consider that since 1900, the world population has skyrocketed from one billion to the cusp of seven billion today, with mid-range projections placing the global total at roughly 9.5 billion by mid-century. And it only took 12 years to add the last billion.

Unlike the United States — which is a water-abundant country by global standards — India is growing weaker with each passing year in its ability to withstand drought or other water-related climate shocks. India’s water outlook is cause for alarm not just because of population growth but also because of climate change-induced shifts in the region’s water supply. Depletion of groundwater stocks in the country’s key agricultural breadbaskets has raised water worries even further. Water scarcity is not some abstract threat in India. As Ashok Jaitly, director of the water resources division at New Delhi’s Energy and Resources Institute, told me this past spring, “we are already in a crisis.”

How the country manages its water scarcity challenges over the coming decades will have repercussions on food prices, energy supplies, and security the world over — impacts that will be felt here in the United States. And India is not the only country wrestling with the intertwined challenges of population growth and water scarcity.

Transboundary Tensions

Several of the world’s most strategically important aquifers and river systems cross one or more major international boundaries. Disputes over dwindling surface- and groundwater supplies have remained local and have rarely boiled over into physical conflict thus far. But given the challenges faced by countries like India, small-scale water disputes may move beyond national borders before the end of this century.

Looming global water shortages, warns a recent World Economic Forum report, will “tear into various parts of the global economic system” and “start to emerge as a headline geopolitical issue” in the coming decades.

This has become a national security issue for the United States. Any country that cannot meet population-linked water demands runs the risk of becoming a failed state and potentially providing fertile ground for international terrorist networks. For that reason, the United States is keeping close track of how water relations evolve in countries like Yemen, Syria, Somalia, Pakistan, and Afghanistan. It is also one of the reasons water security is a key goal of U.S. development initiatives overseas. For instance, between 2007 and 2008, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) invested nearly $500 million across more than 70 countries to boost water efficiency, improve water treatment, and promote more sustainable water management.

More Mouths to Feed, Limited Land to Farm

Water is a critical component of industrial processes the world over — from manufacturing and mining to generating energy — and shapes the everyday lives of the people who rely on it for drinking, cooking, and cleaning. But the aspect of modern society most affected by decreasing water availability is food production. According to the United Nations, agriculture accounts for roughly 70 percent of total worldwide water usage.

Global population growth translates into tens of millions of new mouths to feed with each passing year, straining the world’s ability to meet basic food needs. Given the finite amount of land on which crops can be productively and reliably grown and the constant pressure on farms to meet the needs of a growing population, the 20th and early 21st centuries have been marked by periodic regional food crises that were often induced by drought, poor stewardship of soil resources, or a combination of the two. As demographic change continues to rapidly unfold throughout much of Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, the ability of farmers and agribusinesses to keep pace with surging food demands will be continually challenged. Food shortages could very well emerge as a staple of 21st century life, particularly in the developing world.

Mirroring the growing burden on farmland will be a growing demand for water resources for agricultural use — and the outlook is not promising. According to a report from the International Water Management Institute in Sri Lanka, “Current estimates indicate that we will not have enough water to feed ourselves in 25 years’ time.”

As one of the world’s largest agricultural producers, the United States will be affected by this food crisis in multiple ways. Decreased food security abroad will increase demand for food products originating from American breadbaskets in California and the Midwest, possibly resulting in more intensive (and less sustainable) use of U.S. farmland. It may also drive up prices at the grocery store. Booming populations in east and south Asia could affect patterns of global food production, particularly if severe droughts spark downturns in food production in key Chinese or Indian agricultural centers. Such an outcome would push those countries to import huge quantities of grain and other food staples to avert widespread hunger — a move that would drive up food prices on the global market, possibly with little advance warning. Running out of arable land in the developing world could produce a similar outcome, Upmanu Lall, director of the Columbia Water Center at Columbia University, said via email.

Changing Tastes of the Developing World

Economic modernization and population growth in the developing world could affect global food production in other ways. In many developing countries, rising living standards are prompting changes in dietary preferences: More people are moving from traditional rice- and wheat-based diets to diets heavier in meat. Accommodating this shift at the global level results in greater demand on “virtual water” — the amount of water required to bring an agricultural or livestock product to market. According to the World Water Council, 264 gallons of water are needed to produce 2.2 pounds of wheat (370 gallons for 2.2 pounds rice), while producing an equivalent amount of beef requires a whopping 3,434 gallons of water.

In that way, the growing appeal of Western-style, meat-intensive diets for the developing world’s emerging middle classes may further strain global water resources. Frédéric Lasserre, a professor at Quebec’s Laval University who specializes in water issues, said in an interview about his book Eaux et Territories, that at the end of the day, it simply takes far more water to produce the food an average Westerner eats than it does to produce the traditional food staples of much of Africa or Asia.

Continue reading part two of “Turning Up the Water Pressure” here.

Sources: Columbia Water Center, ExploringGeopolitics.org, International Water Management Institute (Sri Lanka), Population Reference Bureau, The Energy and Resources Institute (India), United Nations, USAID, World Economic Forum, World Water Council.

Photo Credits: “Ganges By Nightfall,” courtesy of flickr user brianholsclaw, and “Traditional Harvest,” courtesy of flickr user psychogeographer. -

Watch: Cynthia Brady on Natural Resources, Climate Change, and Conflict at USAID

›“While we know that natural resources alone are neither necessary nor sufficient to drive conflict, we do know that competition over resources and their revenues often helps to drive conflict and to sustain it over time,” said Cynthia Brady, a senior conflict advisor at USAID’s Office of Conflict Management and Mitigation. “We also know that climate change impacts are going to interact with those dynamics, so we need to better understand how, in order to really program effectively against it in the future.”

Brady spoke to an audience of peacebuilding professionals at the 2010 Alliance for Peacebuliding Conference in Annapolis, Maryland, this fall. She noted that the issue of climate security is a relatively new one and when talking about the risks of climate-related conflict, it’s important to avoid hyperbole.

“The science of analyzing both the risks of climate impacts and the risks of conflict is pretty uncertain – they’re both still evolving,” Brady said. “There’s a very limited evidence base of real-world analysis from which we draw about this intersection.”

“I think it’s really important that we avoid over-simplification and we really focus, as peacebuilding and conflict practitioners, on the reality that conflict is such a complex phenomenon, and that opens a lot of opportunities for various points of intervention,” said Brady. -

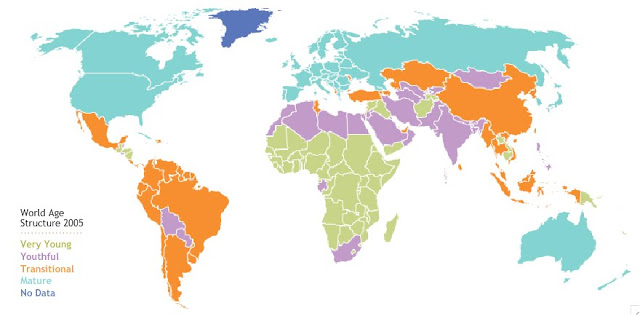

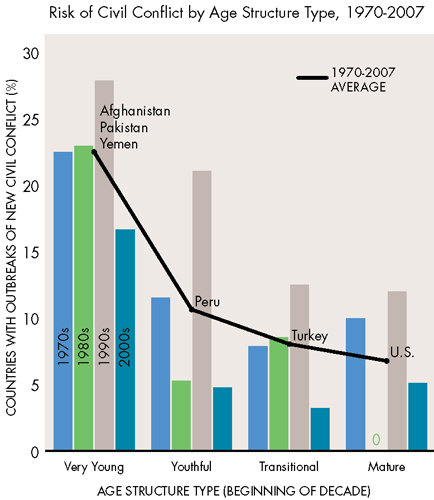

Demographic Security Comes to the Hill

›December 16, 2010 // By Hannah Marqusee“We are now in an unprecedented era of demographic divergence,” said Population Action International’s Elizabeth Leahy Madsen at a September briefing held by Congressman John Tierney’s Subcommittee on National Security and Foreign Affairs and Congressman Russ Carnahan’s Subcommittee on International Organizations, Human Rights and Oversight.

Eighty percent of the world’s conflicts occur in places where 60 percent or more of the population is under 30, and 90 percent of countries with young populations have weak governments, said Chairman Tierney in his opening remarks. He said that while such demographic trends “appear to be issues for the future…it is important that we start this dialogue today, so that we can make steps to address [them].” ECSP Director Geoff Dabelko and the Stimson Center’s Richard Cincotta joined Madsen on the panel titled, “The Effects of Demographic Change on Global Security,” at the Capitol Visitor Center.

Youth Bulges and National Security

The countries of greatest security threat to the United States are also those with the youngest age structures and rapidly increasing populations, said Madsen. By next year, the world’s population will have reached seven billion, with 95 percent of that growth occurring in the developing world.

Large youthful populations can be a source of national strength because they provide innovation and manpower, said Dabelko, but without significant investment they may also contribute to state instability. When there are often few opportunities to obtain a job or an education for young people, there are low “opportunity costs” to joining a rebel group, said Madsen.

State instability can be affected by youth bulges, shifting religious or ethnic compositions, or food and water insecurity, but age-structural transitions are the strongest indicator of state performance, said Cincotta. Despite conventional wisdom, there is actually little evidence to link state failure with premature adult mortality due to AIDS or a high male-to-female ratio, he added.

It is not only developing countries with high fertility rates that face demographic difficulties, Cincotta noted. Countries such as Japan and Germany will soon have reached a “post-mature” age structure in which their aging populations and comparatively small workforces will tax state institutions and threaten economic stability.

Population Policies: Using “Soft Tools” to Improve National Security

Recently, leaders in the U.S. government have been paying increased attention to the linkages between demography and security through the “three Ds:” diplomacy, development, and defense. In 2008, the National Intelligence Council’s Global Trends 2025 included demographic assessments to analyze security trends, and this year, the National Security Strategy featured demographic trends along with the environment and other non-traditional areas.

Dabelko said that while this growing recognition signals progress, the “hard tools” of the traditional security community must be bolstered with “soft tools” commonly used by the international aid community, such as female empowerment, education, health services and youth employment.

Madsen argued that empowering the 215 million women with an unmet need for family planning worldwide through increased funding for voluntary family planning programs is a cost-effective way to shape population trends and ultimately reduce security threats.

“Demography is not destiny,” said Madsen. “Family planning has been an unsung signature of U.S. foreign assistance for decades.”

Similarly, Cincotta said that policies should help states transition out of youth bulges, and help countries with aging populations reform social institutions to protect older people.

Dabelko added that while progress has been made in acknowledging the linked nature of population trends and national security, there is significant room for improvement. Pointing to the successes of integrated population, health, and environment (PHE) programs, which provide environmental conservation and family planning services simultaneously, he called for similar programs to address population dynamics and conflict prevention. Long-term solutions call for coordinated resources and integrated strategies, he said.

Read the speakers’ full remarks: Chairman John F. Tierney, Richard Cincotta, Geoff Dabelko, and Elizabeth Leahy Madson (slides).

Sources: Guttmacher Institute, Population Action International, National Intelligence Council.

Image Credits: “World Age Structure 2005” and “Risk of Civil Conflict by Age Structure Type, 1970-2007,” courtesy of Population Action International. -

An Integrated Climate Dialogue

COP-16 Cancun Coverage Wrap-up

›December 13, 2010 // By Schuyler NullAfter focused last-minute negotiations, the UNFCCC COP-16 parties meeting in Mexico finally reached an agreement on a package being called “The Cancun Agreements” on Saturday. One of the most important impacts of the agreement (also referred to as the “balanced package”) is the establishment of a green climate fund which will help developing countries adapt to and mitigate the effects of climate change.

For more on the green fund as well as the integration of gender, population, development, and even a little bit of security in the broader climate dialogue, see The New Security Beat’s coverage of Cancun below.- Interview with Karen Hardee: Climate-Proofing Development

- Pop Audio: From Cancun: Roger-Mark De Souza on Women and Integrated Climate Adaptation Strategies

- Guest Contributor Alex Stark: From Cancun: Getting a Climate Green Fund

- The Number Left Out: Bringing Population Into the Climate Conversation

Kicking off our coverage was an email interview with Karen Hardee, visiting fellow with the Population Reference Bureau, on “climate-proofing” development. Hardee gives a brief overview of the UN National Adaptation Programmes of Action system and the current state climate adaptation integration in international development. She points out that one of the enduring positives from COP-15 was a renewed focus on financing tools that has permeated to the top levels of the UN.

Hardee also touched on the nascent but largely unfulfilled connection between population growth and resilience, noting that “of the first 41 programs submitted to the UNFCCC…37 noted that population growth exacerbated the effects of climate change, but only six explicitly stated that meeting an unmet demand for RH/FP should be a key priority for their adaptation strategy and only two proposed projects that included RH/FP.”

Next, Population Action International’s Roger-Mark De Souza was kind of enough to speak with us briefly over the phone from the conference itself, providing a run-down on a PAI-sponsored side event focusing on empowering women in climate debates.

“When you look at the negative impacts of climate change, the impacts on the poor and the vulnerable – particularly women – increase, so investing in programs that put women at the center is critical,” De Souza said.

Leaving gender issues, like child and maternal health and education, out of deliberations like those COP-16 are missed opportunities to get more “power for your peso,” he said.

Alex Stark, formerly of CNAS and now with the Adopt a Negotiator program in Cancun, provided an update and a strong argument for one of the most critical elements of the “balanced package” that many are hoping will come out of Cancun – the establishment of an international fund to help pay for adaptation and mitigation programs in developing countries.

Stark provides an insight into some of the chatter on the floor at COP-16 and also outlines the moral, development, and security advantages to supporting a green fund, pointing out that “by managing displacement, migration, and violent conflict driven by the effects of climate change, such as water scarcity, climate change adaptation can help bolster international security and stability.”

“Within the UN process itself,” she writes, “a robust, well-run, equitable green fund would help rebuild the trust lost between developed and developing countries at Copenhagen last year.”

Lastly, Bob Engelman, of the Worldwatch Institute, provides a broad argument for more inclusion of a key variable in climate debates – population (and not in the Ted Turner mold). He enumerates the common pitfalls of population debates, from sensitivities about personal choices to squeamishness about sexuality and reproductive health, and just plain gender bias.

But despite these barriers, says Engelman, population – and not just growth but demographics too – matters in the climate debate and therefore needs to be part of the conversation (an argument he makes more comprehensively in a new report, Population, Climate Change, and Women’s Lives). Echoing De Souza, he concludes by pointing out that although the discussion may be difficult, the solution is relatively simple: “On population, the most effective way to slow growth is to support women’s aspirations.”

“As societies, we have the ability to end the ongoing growth of human numbers – soon, and based on human rights and women’s intentions,” Engelman said. “This makes it easy to speak of women, population, and climate change in a single breath.”

Sources: Population Action International, Slate, UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, The Washington Post, Worldwatch Institute.

Photo Credit: Adapted from “Trees Dead on Shore of Timor-Leste Lake,” courtesy of flickr user United Nations Photo; Roger-Mark De Souza, courtesy of David Hawxhurst/Wilson Center; “Will you back a climate fund?,” courtesy of flickr user Oxfam International; and “Met Office Climate Data – Month by Month (September),” courtesy of flickr user blprnt_van. -

Robert Engelman, Worldwatch Institute

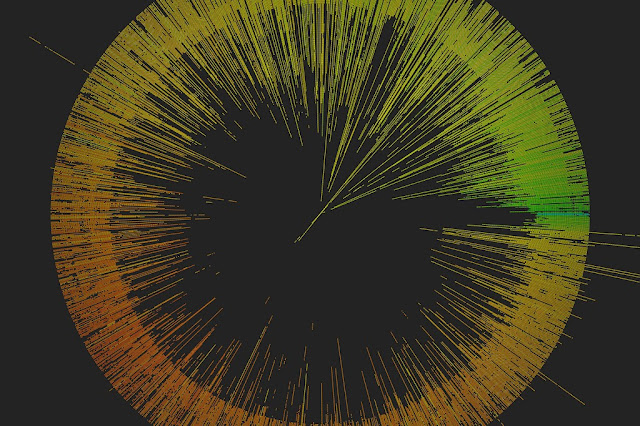

The Number Left Out: Bringing Population Into the Climate Conversation

›December 9, 2010 // By Wilson Center Staff Numbers swirl around climate change.

Numbers swirl around climate change.

So many parts per million of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. So many gigatons of carbon dioxide emitted. So many degrees Celsius of temperature rise that we hope won’t happen. Yet one number rarely comes into play when experts or negotiators talk about the changing atmosphere and the warming of the planet: the number of humans putting heat-trapping gases into the air.

The original version of this article, by Robert Engelman, appeared on the Worldwatch Institute’s Transforming Cultures blog.

The UK Met Office’s data set for September 2009 of more than 1,600,000 temperature readings from 1,700+ stations.

Numbers swirl around climate change.

So many parts per million of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. So many gigatons of carbon dioxide emitted. So many degrees Celsius of temperature rise that we hope won’t happen. Yet one number rarely comes into play when experts or negotiators talk about the changing atmosphere and the warming of the planet: the number of humans putting heat-trapping gases into the air.

The relative silence isn’t hard to understand. Population is almost always awkward to talk about. It’s fraught with sensitivity about who has how many children and whether that is anyone else’s business. It’s freighted with sexuality, contraception, abortion, immigration, gender bias, and other buttons too hot to press into conversation. Yet two aspects of population’s connection to climate change cry out for greater attention – and conversation.

One is that population – especially its growth, but other changes as well – matters importantly to the future of climate change, a statement that as far as I can tell is not challenged scientifically. (The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, for example, accepts the accuracy of the so-called Kaya identity, which names population among the four factors that determine emissions growth from decade to decade.) And, two, addressing population in climate-friendly ways is also fundamentally people-friendly, in that it involves no “population control,” but rather the giving up of control – especially control of women’s bodies by people other than themselves.

A new Worldwatch Institute report, which I authored, offers details, findings, and recommendations on both the importance of population in climate change and how to address it. The report looks at some of the history of the population-climate link – in particular, interesting work by William Ruddiman, who hypothesizes that the agricultural revolution contributed to global warming thousands of years ago. And it addresses the common objection that population growth can’t be that important in greenhouse gas emissions growth because countries with high per capita emissions tend to have smaller families than low-emitting countries.

Equity in per capita emissions, I argue, is an essential goal – and without it, no global effort to shrink emissions can succeed. The imperative of an equal sharing of atmospheric carbon space is among the most powerful arguments for a smaller world population. When greenhouse gases other than carbon dioxide – such as methane and “black carbon” – are considered, per capita emissions gaps are not as wide as many writers believe. And the amount of all these gases that equal emitters can contribute without altering the atmosphere shrinks in direct proportion to population’s growth.

Arguments about population’s role in climate change are unnecessarily heated, however. Even if the growth of human numbers played only a minor role in emissions growth, it would be worth discussing – not because addressing population will somehow resolve our climate predicament, but because ultimately no other strategy on its own will either. We need the widest possible range of strategies – economic, political, technological, and behavioral – that are both feasible and consistent with shared human values.

On population, the most effective way to slow growth is to support women’s aspirations. Almost all women aspire to gain an education, to stand in equality with men, and to make decisions for themselves – including whether and when to give birth. Policies and programs to help women achieve these aspirations exist in many places. But they don’t get the attention, support and funding they deserve. And they are rarely seen as climate-change strategies.

As societies, we have the ability to end the ongoing growth of human numbers – soon, and based on human rights and women’s intentions. This makes it easy to speak of women, population, and climate change in a single breath.

Robert Engelman is vice president for programs at the Worldwatch Institute and the author of “Population, Climate Change, and Women’s Lives.” Please contact him if you are interested in a copy of the report.

Sources: UK Met Office, World Resources Institute.

Image Credit: Adapted from “Met Office Climate Data – Month by Month (September),” courtesy of flickr user blprnt_van, and report cover, courtesy of the Worldwatch Institute. -

Managing the Mekong: Conflict or Compromise?

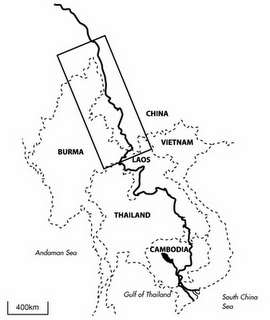

›December 1, 2010 // By Russell SticklorAt nearly 5,000 kilometers long, the Mekong River is one of Asia’s most strategically important transboundary waterways. In addition to providing water for populations in the highlands of southern China, the Mekong helps support some 60 million people downstream in Southeast Asia, where the river is a key component of agricultural production and economic development.

In recent years, however, the Mekong has emerged as a flashpoint for controversy, pitting China against a coalition of downstream nations that includes Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam. The countries of the Lower Mekong argue that Beijing’s construction of multiple dams on the Upper Mekong is robbing them of critical water resources, by decreasing both the quality and quantity of water that makes it through Chinese floodgates and spillways. China, however, mindful of soaring energy demand at home, has continued its campaign to harness the hydroelectric potential of the Upper Mekong and its tributaries – but at what cost to the environment and Beijing’s relationships with Southeast Asia?

China’s Hand on the Faucet

China’s total energy demand just recently passed the United States and is expected to continue to increase in the near-term – by 75 percent over the next 25 years, according to the International Energy Agency.

As a result, Beijing has been looking to bolster its energy security by reaching out to develop energy resources in Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East, as well as along the Mekong and in the East and South China Seas.

In that context, China’s aggressive hydroelectric development of the Upper Mekong — known in China as the Láncang Jiang (shown in the boxed area of the map at right) — makes perfect sense. The river’s sizeable elevation drops make it a rich source of energy; already, 15 large-scale dams have either been completed or are under construction on the Upper Mekong in Tibet and Yunnan.

Those dams also provide China with enormous geopolitical leverage over downstream nations. With little more than the flick of a switch, the Chinese government could substantially curtail the volume of flow entering the Lower Mekong basin. Doing so would of course be tantamount to an act of war, since depleted flow volumes in the Lower Mekong would hinder crop irrigation, jeopardize food security, and endanger the health of the region’s economically critical freshwater fisheries, which are among the world’s most productive. Chinese floodgates and spillways essentially give Beijing de facto control over Southeast Asia’s water security.

The View Downstream

To date, China has never threatened to deliberately reduce the flow of the Mekong to its downstream neighbors. Nevertheless, the perception of threat in Southeast Asian capitals remains high.

Already, a number of the region’s governments — represented formally through the Mekong River Commission, a 15-year-old organization that China still has not joined as a full-fledged member — have complained that completed or in-progress Chinese dams are resulting in less water entering their countries, a phenomenon that becomes particularly pronounced during periods of drought, as observed this summer. Further, there is also the issue of water quality. Since Chinese dams trap silt being flushed out of the Himalayas, that nutrient-rich material cannot be carried downstream, where it historically has helped create fertile soils in the floodplains of the Lower Mekong basin.

Quality and quantity concerns aside, there are also structural issues concerning how Beijing goes about its business on the Upper Mekong. Since it is only a “Dialogue Partner” to members of the Mekong River Commission, China is not required to seek approval from downstream nations on hydroelectric development of the river’s Chinese stretch, even though that development has both direct and indirect implications for water security in the Lower Mekong basin. China has even shown a penchant for deliberate secrecy as it develops its stretch of the river, choosing to share a minimal amount of hydrological data with downstream neighbors and typically refraining from even announcing new dam projects.

“The Security Implications Could Hardly Be Greater”

Given its geographic position, Cambodia is particularly vulnerable to China’s stewardship decisions. With one of the poorest populations in Southeast Asia and also one of the highest fertility rates, at 3.3 births per woman, the potential for water scarcity issues is real. By mid-century, its population is projected to jump from its current 15 million to nearly 24 million.

“The government of Cambodia will be entirely at the mercy of Beijing,” said Wilson Center Scholar and Southeast Asian security expert Marvin Ott. “For Cambodia, the question becomes how they can curry China’s favor so as to avoid coercive use of the Mekong — or find some way of exerting counter-pressure on Beijing.”

Overall, population for mainland Southeast Asia is projected to rise from its current 232 million to 292 million by 2050. This growth will require increased agricultural output across the region and thus increased reliance on the waters of the Lower Mekong. The Lower Mekong nations’ shared dependency on the river and China’s continued unilateralism in the Upper Mekong could have serious repercussions for the region, said Ott:The security implications could hardly be greater for the downstream states. With the dams, China will have literal control over the river system that is the lifeblood of Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam. The power this gives China is equivalent to an invasion and occupation of a country by the Chinese army.

For its part, the PRC maintains that water woes in the Lower Mekong are not its doing. In response to the chorus of Southeast Asian claims that China diverts or stores more than its fair share of water, Beijing’s typical refrain has been that blame for low water levels downstream lies not with Chinese water resource management but with heightened precipitation variability associated with climate change. Chinese water officials also contend that the Lower Mekong countries’ complaints are misdirected because water from the Chinese-controlled sections of the Upper Mekong basin accounts for less than 20 percent of the Mekong’s total flow volume by the time the river reaches its natural outlet in the South China Sea.

There are some indications, however, that China may be experimenting with a more open approach to engaging downstream nations. Earlier this year, China overturned precedent by offering top Southeast Asian government officials a tour of what had once been a top-secret hydro project, the mammoth Xiaowan dam. Some critics insisted Beijing’s fear of growing U.S. influence in the Lower Mekong helped motivate the rare show of transparency, while others said it was a means to curry favor with Southeast Asian nations so that they would support China’s controversial resource-development strategies in the South China Sea. Yet regardless of motive, Beijing’s move away from secrecy – if sustained – could do a great deal to smooth over regional tensions.

Dammed If You Do, Damned If You Don’t

Beyond some limited transparency, Beijing also hopes to mitigate concerns about development of the Upper Mekong by offering funding or logistical support for similar large-scale hydroelectric facilities on the Lower Mekong. The move has been largely welcomed by the Mekong River Commission countries, which envision dams of their own generating much-needed energy input for national grids, accelerating continued economic modernization, and enhancing flood control. As of 2009, there were 12 dam projects for stretches of the Mekong south of the Chinese border and many more planned for key tributaries.

The danger in such deal-making is that the environmental costs will be lost in the shuffle. A series of major dams would fundamentally alter the Mekong’s hydrology, which could lead to the degradation of sensitive riverine ecosystems, the disruption of upstream migratory routes for fish that serve as local dietary staples, and the decline of fresh water fisheries that form the backbone of many local economies.

Given the long-term effects on the food, environmental, and economic security of the Lower Mekong heartland, Beijing’s attempt to ease water tensions with a new round of dam construction may end up doing far more harm than good. Unfortunately, with both China and the Mekong River Commission countries currently viewing the dam proposals as something of a win-win, planning and construction are likely to move forward over the coming years.

Sources: Financial Times, Foreign Policy, International Institute for Strategic Studies, Los Angeles Times, Mekong River Commission, National Geographic, New Asia Republic, Phnom Penh Post, Population Reference Bureau, Stimson Center.

Photo Credits: “Xiaowan Dam Site (Yunnan Province, China, 2005),” (Top) courtesy of flickr user International Rivers; Map (Middle) courtesy of International Rivers; “Thailand – Isaan, Mekong River,” (Bottom) courtesy of flickr user vtveen.