-

As Somalia Sinks, Neighbors Face a Fight to Stay Afloat

›May 14, 2010 // By Schuyler NullThe week before the international Istanbul conference on aid to Somalia, the UN’s embattled envoy to the country, Ahmedou Ould-Abdallah, warned the Security Council that if the global community “did not take the right action in Somalia now, the situation will, sooner or later, force us to act and at a much higher price.”

The UN High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) also issued strong warnings this week. Deputy High Commissioner Alexander Aleinikoff said in Geneva, “The displacement crisis is worsening with the deterioration of the situation inside Somalia and we need to prepare fast for new and possibly large-scale displacement.”

But the danger is not limited to Somalia. The war-torn country’s cascading set of problems – criminal, health, humanitarian, food, and environmental – threaten to spill over into neighboring countries.

A Horrendous Humanitarian Crisis

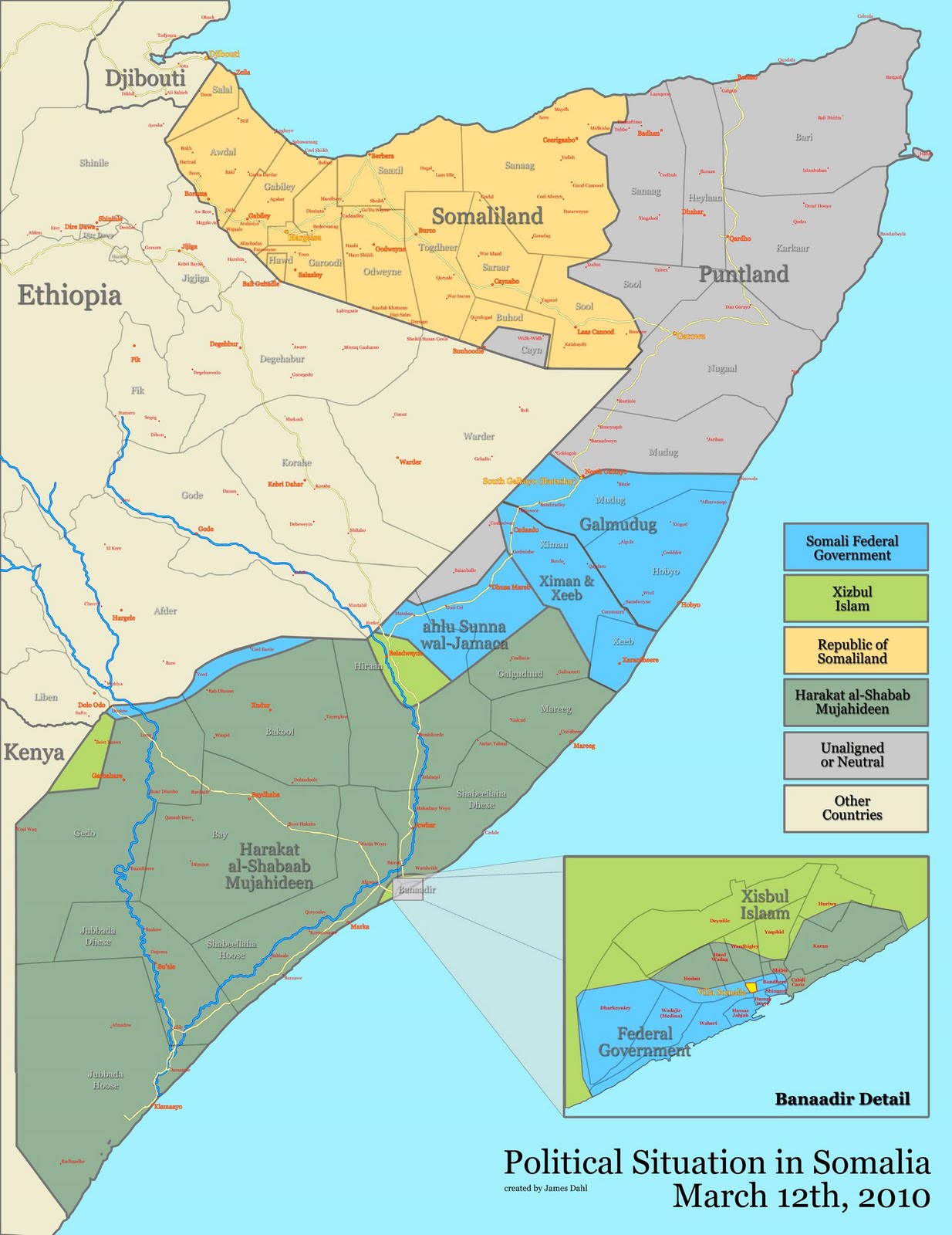

The UN- and U.S.-backed Transitional Federal Government (TFG) controls only parts of Mogadishu and small portions of central Somalia, while insurgent group Al Shabab controls nearly the entire south. The northern area is divided into semi-autonomous Somaliland and Puntland, which also fall outside of the transitional government’s control.

But the civil war is only one part of what Ould-Abdallah called a “horrendous” humanitarian crisis.

According to the UN, 3.2 million Somalis rely on foreign assistance for food – 43 percent of the population – and 1.4 million have been internally displaced by war. Another UN-backed study finds that approximately 50 percent of women and 60 percent of children under five are anemic. Most distressing, the UN Security Council reported in March that up to half of all food aid sent to Somalia is diverted from people in need by militants and corrupt officials, including UN and government employees.

Because of the country’s large youth bulge – 45 percent of Somalia’s population is under the age of 15 – food and health conditions are expected to get much worse before they get better. In the 2009 Failed States Index, Somalia ranks as the least stable state in the world and, along with Zimbabwe, has the highest demographic pressures.

Islamic Militants and the Battle for the High Seas

Yet the West continues to focus on the sensational pirate attacks on Somalia’s coast. The root cause of these attacks is not simply lawlessness say Somali officials, instead, they began partly as desperate attempts to stop foreign commercial fleets from depleting Somalia’s tuna-rich, lawless shores. A 2006 High Seas Task Force reported that at any given time, “some 700 foreign-owned vessels are engaged in unlicensed and unregulated fishing in Somali waters, exploiting high value species such as tuna, shark, lobster and deep-water shrimp.”

The transitional government opposes the fishermen-turned-pirates, but can do little to stop them. Al Shabab has thus far allowed pirates to operate freely in their territory. Their tacit approval may be tied to reports that the group has received portions of ransoms in the past.

Another hardline Islamist group, Hizbul Islam, recently took over the pirate safe haven of Haradhere, allegedly in response to local pleas for better security, but the move may simply have been part of an ongoing struggle with Al Shabab for control of pirate ransoms and port taxes – one of the few sectors of the economy that has remained lucrative.

“I can say to you, they are not different from pirates — they also want money,” Yusuf Mohamed Siad, defense minister with Somalia’s TFG, told Time Magazine.

A Toxic ThreatInitially the pirates claimed one of their goals was to ward off “mysterious European ships” that were allegedly dumping barrels of toxic waste offshore. UN envoy Ould-Abdallah told Johann Hari of The Independent in 2009 that “somebody is dumping nuclear material here. There is also lead, and heavy metals such as cadmium and mercury – you name it.” After the 2005 tsunami, “hundreds of the dumped and leaking barrels washed up on shore. People began to suffer from radiation sickness, and more than 300 died,” Hari reports.

Finnish Minister of Parliament Pekka Haavisto, speaking to ECSP last year, urged UN investigation of the claims. “If there are rumors, we should go check them out,” said the former head of the UN Environment Program’s Post-Conflict Assessment Unit:I think it is possible to send an international scientific assessment team in to take samples and find out whether there are environmental contamination and health threats. Residents of these communities, including the pirate villages, want to know if they are being poisoned, just like any other community would.

To date, there has been no action to address these claims.

Drought, Deforestation, and Migration

While foreign entities may have been exploiting Somalia’s oceans, the climate has played havoc with the rest of the country. Reuters and IRIN report that the worst drought in a decade has stricken some parts of the interior, while others parts of the country face heavy flooding from rainfall further upstream in Ethiopia.

Land management has also broken down. A 2006 Academy for Peace and Development study estimated that the province of Somaliland alone consumes up 2.5 million trees each year for charcoal, which is used as a cheaper alternative to gas for cooking and heating. A 2004 Somaliland ministry study on charcoal called the issue of deforestation for charcoal production “the most critical issue that might lead to a national environmental disaster.”

West of Mogadishu, Al Shabab has begun playing the role of environmental steward, instituting a strict ban on all tree-cutting – a remarkable decree from a group best known for their brutal application of Sharia law rather than sound governance.

The result of this turmoil is an ever-increasing flow of displaced people – nearly 170,000 alone so far this year, according to the Washington Post – driven by war, poverty, and environmental problems. The burden is beginning to weigh on Somalia’s neighbors, says the UNHCR.

The Neighborhood Effect

One of the largest flows of displaced Somalis is into the Arabian peninsula country of Yemen – itself a failing state, with 3.4 million in need of food aid, 35 percent unemployment, a massive youth bulge, dwindling water and oil resources, and a burgeoning Al Qaeda presence.

In testimony on Yemen earlier this year, Assistant Secretary of State Jeffrey Feltman said that the country’s demographics were simply unsustainable:Water resources are fast being depleted. With over half of its people living in poverty and the population growing at an unsustainable 3.2 percent per year, economic conditions threaten to worsen and further tax the government’s already limited capacity to ensure basic levels of support and opportunity for its citizens.

Other neighboring countries face similar crises of drought, food shortage, and overpopulation – Ethiopia has 12 million short of food, Kenya, 3.5 million, says Reuters. UNHCR reports that in Djibouti, a common first choice for fleeing Somalis, the number of new arrivals has more than doubled since last year, and the country’s main refugee camp is facing a serious water crisis.

A Case Study in Collapse

The ballooning crises of Somalia encompass a worst-case scenario for the intersection of environmental, demographic, and conventional security concerns. Civil war, rapid population growth, drought, and resource depletion have not only contributed to the complete collapse of a sovereign state, but could also lead to similar problems for Somalia’s neighbors – threatening a domino effect of destabilization that no military force alone will be able to prevent.

Speaking at a naval conference in Abu Dhabi this week, Australian Vice Admiral Russell Crane told ASD News that, “The symptoms (piracy) we’re seeing now off Somalia, in the Gulf of Aden, are clearly an outcome of what’s going on on the ground there. As sailors, we’re really just treating the symptoms.”

Sources: Academy for Peace and Development, AP, ASD News, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Christian Science Monitor, Foreign Policy, High Seas Task Force, Independent, IRIN, New York Times, Population Action, Population Reference Bureau, Reuters, Telegraph, Time, UN, US State Department, War is Boring, Washington Post.

Photo Credits: “Don’t Swim in Somalia (It’s Toxic)” courtesy of Flickr user craynol and “Somalia map states regions districts” courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. -

The Food Security Debate: From Malthus to Seinfeld

›Charles Kenny’s latest article, “Bomb Scare: The World Has a Lot of Problems; an Exploding Population Isn’t One of Them” reminds me of a late-night episode of Seinfeld: a re-run played for those who missed the original broadcast. Kenny does a nice job of filling Julian Simon’s shoes. What’s next? Will Jeffrey Sachs do a Paul Ehrlich impersonation? Oh, Lord, help me; I hope not.

I’ve already seen the finale. Not the one where Jerry, George, and Kramer go to jail — the denouement of the original “Simon and Ehrlich” show. After the public figured out that each successive argument (they never met to debate) over Malthus’s worldview was simply a rehash of the first — a statement of ideology, rather than policy — they flipped the channel.

Foreign Policy could avoid recycling this weary and irrelevant 200-year-old debate by instead exploring food security from the state-centric perspective with which policymakers are accustomed. While economists might hope for a seamless global grain production and food distribution system, it exists only on their graphs.

Cropland, water, farms, and markets are still part and parcel of the political economy of the nations in which they reside. Therefore they are subject to each state’s strategic interests, political considerations, local and regional economic forces, and historical and institutional inefficiencies.

From this realistic perspective, it is much less important that world population will soon surpass 7 billion people, and more relevant that nearly two dozen countries have dropped below established benchmarks of agricultural resource scarcity (less than 0.07 hectares of cropland per person, and/or less than 1000 cubic meters of renewable fresh water per person).

Today, 21 countries—with some 600 million people—have lost, for the foreseeable future (and perhaps forever), the potential to sustainably nourish most of their citizens using their own agricultural resources and reasonably affordable technological and energy inputs. Instead, these states must rely on trade with–and food aid from–a dwindling handful of surplus grain producers.

By 2025, another 15 countries will have joined their ranks as a result of population growth alone (according to the UN medium variant projection). By then, about 1.4 billion people will live in those 36 states—with or without climate change.

For the foreseeable future, poor countries will be dependent on an international grain market that has recently experienced unprecedented swings in volume and speculation-driven price volatility; or the incentive-numbing effects of food aid. As demand rises, the poorest states spend down foreign currency reserves to import staples, instead of using it to import technology and expertise to support their own economic development.

Meanwhile, wealthier countries finding themselves short of water and land either heavily subsidize local agriculture (e.g., Japan, Israel, and much of Europe) or invest in cropland elsewhere (e.g., China, India, and Saudi Arabia). And some grain exporters—like Thailand—decided it might be safer to hold onto some of their own grain to shield themselves from a future downturn in their own harvest. All of this is quite a bit more complex than either Malthus could have imagined or Kenny cares to relate.

It hardly matters why food prices spiked and remained relatively high—whether it is failed harvests, growing demand for grain-fed meat, biofuels, profit-taking by speculators, or climate change. Like it or not, each has become an input into those wiggly lines called grain price trends, and neither individual states nor the international system appears able or willing to do much about any of them.

From the state-centric perspective, hunger is sustained by:1. The state’s inability or lack of desire to maintain a secure environment for production and commerce within its borders;

In some countries, aspects of population age structure or population density could possibly affect all three. In others, population may have little effect at all.

2. Its incapacity to provide an economic and trade policy environment that keeps farming profitable, food markets adequately stocked and prices reasonably affordable (whether produce comes from domestic or foreign sources); and

3. Its unwillingness or inability to supplement the diets of its poor.

What bugs me most about Kenny’s re-run is its disconnect with current state-centric food policy concerns, research, and debates (even as the U.S. administration and Congress are focusing on food security, with a specific emphasis on improving the lives of women.—Ed.).

Another critique of Malthus’s 200-year-old thesis hardly informs serious policy discussions. Isn’t Foreign Policy supposed to be about today’s foreign policy?

Richard Cincotta is a consultant with the Environmental Change and Security Program and the demographer-in-residence at the H.L. Stimson Center in Washington, DC.

Photo Credit “The Bombay Armada” courtesy of Flickr user lecercle. -

Population and Sustainability

›“The MAHB, the Culture Gap, and Some Really Inconvenient Truths,” authored by Paul Ehrlich and appearing in the most recent edition of PLoS Biology, is a call for greater participation in the Millennium Assessment of Human Behavior (MAHB). MAHB was created, he writes, because societies understand the magnitude of environmental challenges, yet often still fail to act. “The urgent need now is clearly not for more natural science…but rather for better understanding of human behaviors and how they can be altered to direct Homo sapiens onto a course toward a sustainable society.” MAHB aims to create an inclusive global discussion of “the human predicament, what people desire, and what goals are possible to achieve in a sustainable society” in the hopes of encouraging a “rapid modification” in human behavior. The BALANCED Project, lead by the Coastal Resource Center at the University of Rhode Island, released its first “BALANCED Newsletter.” To be published biannually, the newsletter highlights recent PHE fieldwork, unpacks aspects of particular PHE projects, and shares best practices in an effort to advance the BALANCED Project’s goal: promoting PHE approaches to safeguard areas of high biodiversity threatened by population pressures. The current edition examines the integration of family planning and reproductive health projects into marine conservation projects in Kenya and Madagascar, a theater-based youth education program in the Philippines, and the combining of family planning services with gorilla conservation work in Uganda. The newsletter also profiles two “PHE Champions,” Gezahegh Guedta Shana of Ethiopia and Ramadhani Zuberi of Tanzania.

The BALANCED Project, lead by the Coastal Resource Center at the University of Rhode Island, released its first “BALANCED Newsletter.” To be published biannually, the newsletter highlights recent PHE fieldwork, unpacks aspects of particular PHE projects, and shares best practices in an effort to advance the BALANCED Project’s goal: promoting PHE approaches to safeguard areas of high biodiversity threatened by population pressures. The current edition examines the integration of family planning and reproductive health projects into marine conservation projects in Kenya and Madagascar, a theater-based youth education program in the Philippines, and the combining of family planning services with gorilla conservation work in Uganda. The newsletter also profiles two “PHE Champions,” Gezahegh Guedta Shana of Ethiopia and Ramadhani Zuberi of Tanzania. “Human population growth is perhaps the most significant cause of the complex problems the world faces,” write authors Jason Collodi and Freida M’Cormack in “Population Growth, Environment and Food Security: What Does the Future Hold?,” the first issue of the Institute of Development Studies‘ Horizon series. The impacts of climate change, poverty, and resource scarcity, they write, are not far behind. Collodi and M’Cormack highlight trends in, and projections for, population growth, the environment, and food security, and offer bulleted policy recommendations for each. Offering greater access to family planning; levying global taxes on carbon; introducing selective water pricing; and removing subsidies for first-generation biofuels are each examples of suggestions advanced by the authors to meet the interrelated challenges.

“Human population growth is perhaps the most significant cause of the complex problems the world faces,” write authors Jason Collodi and Freida M’Cormack in “Population Growth, Environment and Food Security: What Does the Future Hold?,” the first issue of the Institute of Development Studies‘ Horizon series. The impacts of climate change, poverty, and resource scarcity, they write, are not far behind. Collodi and M’Cormack highlight trends in, and projections for, population growth, the environment, and food security, and offer bulleted policy recommendations for each. Offering greater access to family planning; levying global taxes on carbon; introducing selective water pricing; and removing subsidies for first-generation biofuels are each examples of suggestions advanced by the authors to meet the interrelated challenges. -

Philippines’ Bohol Province: Elin Torell Reports on Integrating Population, Health, and Environment

›For 10 years, I have been working on marine conservation in Tanzania with the University of Rhode Island’s Coastal Resources Center. As part of that effort, I’ve helped forge links between HIV/AIDS prevention in vulnerable fishing communities and marine conservation. However, family planning and reproductive health (FP/RH) were relatively new to me. But a recent study tour of an integrated Population, Health, and Environment (PHE) program in the Philippines helped me understand that combining family planning services and marine conservation can help reduce overfishing and improve food security.

Together with developing country representatives from seven African and Asian countries, I spent two weeks in February visiting three PHE learning sites and a marine protected area in Bohol province in the central Philippines, as part of a South-to-South study tour sponsored by the USAID-funded BALANCED Project, for which I work. The tour focused on the activities of the 10-year-old Integrated Population and Coastal Resource Management Initiative (IPOPCORM) project, which is run by PATH Foundation Philippines, Inc. (PFPI).

IPOPCORM has garnered a wealth of lessons learned and best practices to share with PHE newbies like me. Its integrated programs train people to be community-based distributers (CBDs) of contraceptives and PHE peer educators, as well as work with local and regional government officials to build support for family planning as a means to improve food security.

I was most impressed with the ways in which PFPI identifies and cultivates dynamic and motivated local leaders–men, women, and especially youth–to reach out to the members of their community who are highly dependent on marine resources for their survival. My Tanzanian colleagues and I would like to foster the volunteer spirit and “can do” attitudes we experienced through our work in East Africa. (Similar PHE peer educators are successfully working in Ethiopia’s Bale Mountains, as reported by Cassie Gardener in a previous edition of the “Beat on the Ground.”

My favorite part of the tour was a trip to the Verde Island Passage to see PFPI’s efforts in this fragile hotspot. The insights my Tanzanian colleagues and I gained from talking to the field practitioners in the Verde Islands helped us refine our ideas for translating some of the PHE techniques used in the Philippines to the Tanzanian cultural context, including an action plan for strengthening our existing PHE efforts with CBDs and peer educators.

Thanks to the study tour, I now have a better understanding of how to address population pressures in the context of conservation. Overall, my Tanzanian colleagues and I were inspired by the successes we saw firsthand and hope to emulate them to some degree in our own projects.

Elin Torell is a research associate at the Coastal Resources Center at the University of Rhode Island. She is the manager of CRC’s Tanzania Program and coordinates monitoring, evaluation, and learning within the BALANCED project. -

Thinking Outside the (Lunch) Box: Meat and Family Planning

›May 3, 2010 // By Dan AsinJoel Cohen, a renowned population expert and professor at Columbia and Rockefeller universities, recently gave a lecture simply titled “Meat.” As it was co-sponsored by the International Food Policy Research Institute and the Population Reference Bureau, I was hoping for an insightful discussion of meat eating and its implications for feeding a world of nine billion. While I think Cohen avoided the question of whether meat eating is ultimately sustainable, I was pleased that he included two key insights: the potential for family planning services to contribute to food security, and the importance of using multidisciplinary approaches to solve today’s global problems.

Family Planning for Food Security

In working to improve food security, Cohen said policymakers and practitioners need to focus on those who are most vulnerable. To this end, he identified five groups and suggested targeted policies for each:

While the healthy eating policies will not surprise food security experts, his recommendations on family planning might. He highlighted what should be–but is not always–apparent: that tackling food security without thought for family planning is like attempting to fill an empty bucket without first plugging the holes.

Feeding the one billion hungry people in the world today is an enormous challenge that cannot be met by any single policy. Instead, it will take an array of partial solutions, and offering family planning services to women and young people is an important part of the package. Such projects can help reduce the number of children being born into hunger by allowing women and couples to assess their economic and food situations and plan according to their needs and wishes. Voluntary family planning services and materials will not solve the food security challenge on their own, but they can make it more manageable, especially in the long run.

Family planning’s potential contribution to food security is just one part of Cohen’s larger take-home message: population, economics, environment, and culture all interact. To meet today’s multidisciplinary challenges, single-sector approaches are not up to task.

The Many Faces of Meat

Cohen offered two competing perspectives on meat eating. On the one hand, average global meat production generates a fraction of the calories and protein, per unit of land, that could be derived from plant sources. It is likely the “largest sectoral source of water pollution,” said Cohen, and is at least partly responsible for the spread of over a dozen zoonotic diseases. It contributes to only 1.4 percent of world GDP while comprising 8 percent of world water consumption.

These hidden “virtual water” costs made headlines in Britain the other week, when a study on global water security published by the Royal Academy of Engineering popularized the Water Footprint Network’s earlier findings that that an average kilogram of beef requires 15,500 liters of water–over eight times the volume needed to produce the equivalent weight in soybeans and greater than 10 times that needed for the equivalent amount of wheat.

On the other hand, Cohen pointed out that meat production provides livelihoods for an estimated 987 million of the world’s rural poor, and has important cultural significance in many societies. And it can provide many essential nutrients, even in small doses.

In one study he cited, children living in Kenya who were provided 1 ounce of meat a day received 50 percent of their daily protein requirements and showed greater increases in physical activity and development, verbal and arithmetic test scores, and initiative and leadership behaviors as opposed to students who received the calorie-equivalent in milk or fat.

The Four Factors: Population, Economics, Environment, and Culture

Clearly, Cohen’s four factors all come in to play when evaluating meat’s role in food security. An analysis of any global health issue that looks at only one factor would miss indispensable parts of the problem.

“Population interacts with economics, environment, and culture,” Cohen concluded. “If you use that checklist when somebody gives you a simple-minded solution to a problem, you can save yourself a lot of simple-minded thinking.”

Photo: Pigs on a farm, courtesy Flickr user visionshare. -

Food Security Comes to Capitol Hill, Part Two: Women’s Edition

›April 30, 2010 // By Schuyler NullThe focus on food security on Capitol Hill continued with Wednesday’s House Hunger Caucus panel, “Feeding a Community, Country and Continent: The Role of Women in Food Security.” According to panel organizers Women Thrive Worldwide, “over half the food in developing countries – and up to 80 percent in sub-Saharan Africa – is grown by women farmers, who also account for seven in ten of the world’s hungry.”

The panel illuminated some of the inequities routinely faced by female farmers that often prevent them from using the same inputs as men (tools, fertilizer, etc.), bar their access to credit, and force them onto less productive land.

“Women around the world face unique economic and social barriers in farming and food production,” said Nora O’Connell of Women Thrive Worldwide. “But they are key to increasing food security and ending hunger, and all international programs must take their needs into account.”

Panelist David Kauck of the International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) cited the State Department’s Consultation Document on the Global Hunger and Food Security Initiative: “Economic output could be increased by 15-40 percent and under-nutrition reduced by 15 million children simply by providing women with assets equal to those of men.”

According to the 2008 ICRW report, A Significant Shift: Women, Food Security, and Agriculture in a Global Marketplace:Women also are more likely than men to spend their income on the well-being of their families, including more nutritious foods, school fees for children and health care. Yet agricultural investments do not reflect these facts. Women in forestry, fishing and agriculture received just 7 percent of total aid for all sectors.

One of the most fundamental problems faced by women in developing countries is a lack of basic education leading to illiteracy and innumeracy, making it difficult for women to understand agricultural policy or the fair market values of their products. Therefore, men are much more likely to control valuable markets.

In addition, women are less likely to learn about and adopt new agricultural technologies and best practices. Lydia Sasu, director of the Development Action Association, said that when she attended agricultural school in Ghana she was one of only three women, compared to more than 40 men, in her class.

Women in developing countries rarely own the land they farm, which can make it difficult to apply for credit and extension services without collateral. According to the ICRW report:In Uganda, women account for approximately three out of four agricultural laborers and nine out of 10 food-producing laborers, yet they own only a fraction of the land. Women in Cameroon provide more than 75 percent of agricultural labor yet own just 10 percent of land. A 1990 study of credit schemes in Kenya, Malawi, Sierra Leone, Zambia and Zimbabwe found that women received less than 10 percent of the credit for smallholders and only 1 percent of total credit to agriculture. Women receive only 5 percent of extension services worldwide, and women in Africa access only 1 percent of available credit in the agricultural sector.

“The fundamental barrier to women in agriculture,” said USAID’s Kristy Cook, “is access to assets.” Cheryl Morden of the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) said we have reached the “tipping point,” where action on this issue seems inevitable on the international policy level. However, she questions how quickly that momentum can translate to change on the ground.

The State Department has made improving women’s lives an important part of both their Global Hunger and Food Security Initiative and the Global Health Initiative. ”Investing in the health of women, adolescents, and girls is not only the right thing to do; it is also the smart thing to do,” said Secretary of State Hillary Clinton in January.

Reproductive health and family planning services will be key to both initiatives. A policy brief by ICRW’s Margaret Greene argues that poor reproductive health can have negative effects on women’s educational and economic opportunities. As Secretary Clinton said, “When women and girls have the tools to stay healthy and the opportunity to contribute to their families’ well-being, they flourish and so do the people around them.”

Photo Credit: “Transplanting at rainfed lowland rice in Madagascar,” courtesy of flickr user IRRI Images. -

Food Security Comes to Capitol Hill, Part One

›April 30, 2010 // By Schuyler NullThis week, the CSIS Task Force on Global Food Security released its latest report, Cultivating Global Food Security: A Strategy for U.S. Leadership on Productivity, Agricultural Research, and Trade.

According to the report, “the number of people living with chronic hunger has jumped to more than 1 billion people – one sixth of the world’s population – and those trends show no signs of reversal: between 2007 and 2008, the number of people suffering from chronic hunger in the developing world increased by 80 million. In 2009, as many as 100 million additional people were pushed into a state of food insecurity.” The riots and instability during the 2008 food crisis vividly illustrate the consequences of failing to address this problem.

The report outlines six broad recommendations for policy makers:1. Develop an integrated, comprehensive approach to food security;

At the report’s Capitol Hill launch, CSIS President John Hamre compared releasing think tank studies to “casting bread on the water, most of it disappears.” However the high profile Congressional presence—including co-chairs Representative Betty McCollum and Senators Richard Lugar and Bob Casey—proves that awareness of the global food security problem is growing.

2. Empower leadership (USAID) and ensure cross-agency coordination;

3. Support country-led (and country-specific), demand-driven plans for agriculture;

4. Elevate agricultural research and development in the United States utilizing the land-grant university system;

5. Leverage the strengths of the private sector to encourage innovation and give farmers better access to credit and markets; and

6. Renew U.S. leadership in using trade as a positive tool for foreign policy and development in order to improve stability and economic growth at home and abroad.

“We are summoned to this issue by our consciences but we also know this is a security issue,” said Sen. Casey. Along with Sen. Lugar, Casey introduced the “Global Food Security Act of 2009,” which seeks to “promote food security in foreign countries, stimulate rural economies, and improve emergency response to food crises, as well as to expand the scope of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 to include conservation farming, nutrition for vulnerable populations, and economic integration of persons in extreme poverty.”

Representative McCollum introduced a similar bill in the House, but neither has made much headway. Senator Lugar said that he hopes the bipartisan and bicameral nature of their bills will help this issue stay afloat during a particularly toxic political atmosphere in Washington.

The release of the CSIS report and its Congressional support is particularly timely, as USAID just announced the 20 focus countries for the “Feed the Future” Initiative, which are Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Mali, Malawi, Mozambique, Rwanda, Senegal, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia in Africa; Bangladesh, Cambodia, Nepal, Tajikistan in Asia; and Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, and, Nicaragua in Latin America. The White House pledged an initial $3.5 billion over three years for the Feed the Future Initiative, with additional pledges from other G-8 and G-20 members to total $18.5 billion.

In addition, the State Department is in the midst of preparing its first-ever (and long-delayed) strategic doctrine for diplomacy and development, the QDDR, in which agricultural development is expected to have a major role.

Speaking on behalf of the State Department, Acting Deputy Assistant Secretary for Trade Policy and Programs William Craft echoed the previous testimony of Deputy Secretary of State Jacob Lew on Feed the Future, saying that the United States believes development should be on par with diplomacy and defense, and is both a strategic and moral imperative.

Next up: “Food Security Comes to Capitol Hill, Part Two” on the particular role women can play in increasing global productivity, if given the chance.

Photo Credit: “World Food Day,” courtesy of flickr user JP. -

A Tough Nut to Crack: Agricultural Remediation Efforts in Afghanistan

›April 5, 2010 // By Julien Katchinoff“It was pretty much a normal day in Afghanistan on Monday.

Though only earning a glancing mention in The New York Times, it is heartening to see a response to the environmental and economic loss of Afghanistan’s once abundant wild pistachio forests. As a result of wide-spread environmental mismanagement and war, the past 30 years have seen a dramatic decline in the wild pistachio woodlands native to Northwestern Afghanistan.

“A couple of civilian casualties caused by insurgents. More investigations into corrupt former ministers. The opening of six new projects in Herat Province by the Italians and the Spaniards, which are the NATO countries in the lead in western Afghanistan. All right, not six, projects, but two or three, and the Spanish announced a pistachio tree-growing program to replace poppies. Pistachios, poppies… maybe pine nuts will be next.”

— At War: An Airborne Afghan Folk Tale, Alissa J. Rubin, New York Times, April 1, 2010

In a 2009 survey of Afghanistan’s environmental challenges, UNEP found that, while in 1970 “the Badghis and Takhar provinces of northern Afghanistan were covered with productive pistachio forests and earned substantial revenue from the sale of nuts,” few remain as the forests have since succumbed to mismanagement, war, and illegal logging.

In this video by the Post-Conflict and Disaster Management Branch of UNEP, scenes of dusty and denuded hillsides clearly show that rural Afghan farmers in search of sustainable livelihoods have few options remaining.

The project mentioned in the New York Times is a recent foray into remediation efforts by a Spanish Provincial Reconstruction Team (PRT) that targets communities previously involved in the production of illegal drugs. In conjunction with the Spanish Agency of Coordination and Development (AECID), the Spanish PRT is working in over 13 sites in Baghdis province–a region once covered in pistachio trees–to help farmers transition to legal crops and restore the traditional pistachio forests to their former prominence. AECID joins the Afghan Conservation Corps (ACC), USAID, NATO and additional partners in promoting remediation projects to reverse deforestation.

Unfortunately, these programs face daunting obstacles, as pistachio and other traditional Afghan cash crops –such as raisins, figs, almonds and other nuts– require substantial re-investments of time, money, and infrastructure development. Furthermore, convincing desperate rural farmers to transition to nearly untested alternative crops is difficult when they are currently counting the days to the spring opium harvest.

Recently, eradication efforts targeting small-scale farms have abated, and increased attention is being paid to facilitating shifts toward new products through free seeds, loans, technical assistance, and irrigation investments. If successful, these projects will grant rural Afghan communities the ability to sustainably and legally provide for their families, providing long-term employment and returns for a region lacking in both money and hope for the future.

Video Credit: UNEP Video, “UNEP observes massive deforestation in Afghanistan” .

Showing posts from category food security.