-

In Colombia, Rural Communities Face Uphill Battle for Land Rights

›November 14, 2011 // By Kayly Ober“The only risk is wanting to stay,” beams a Colombian tourism ad, eager to forget decades of brutal internal conflict; however, the risk of violence remains for many rural communities, particularly as the traditional fight over drugs turns to other high-value goods: natural resource rights.

La Toma: Small Town, Big Threats

In the vacuum left by Colombia’s war on drugs, re-armed paramilitary groups remain a threat to many rural civilians. Organized groups hold footholds, particularly in the northeast and west, where they’ve traditionally hidden and exploited weak governance. Over the past five years, their presence has increased while their aims have changed.

A recent PBS documentary, The War We Are Living (watch below), profiles the struggles of two Afro-Colombian women, Francia Marquez and Clemencia Carabali, in the tiny town of La Toma confronting the paramilitary group Las Aguilas Negras, La Nueva Generacion. The Afro-Colombian communities the women represent – long persecuted for their mixed heritage – are traditional artisanal miners, but the Aguilas Negras claim that these communities impede economic growth by refusing to deal with multinationals interested in mining gold on a more industrial scale in their town.

For over seven years, the Aguilas Negras have sent frequent death threats and have indiscriminately killed residents, throwing their bodies over the main bridge in town. At the height of tensions in 2010, they murdered eight gold miners to incite fear. Community leaders know that violence and intimidation by the paramilitary group is part of their plan to scare and displace residents, but they refuse to give in: “The community of La Toma will have to be dragged out dead. Otherwise we’re not going to leave,” admits community leader Francia Marquez to PBS.

La Toma’s predicament is further complicated by corruption and general disinterest from Bogota. Laws that explicitly require the consent of Afro-Colombian communities to mine their land have not always been followed. In 2010, the Department of the Interior and the Institute of Geology and Minerals awarded a contract, without consultation, to Hector Sarria to extract gold around La Toma and ordered 1,300 families to leave their ancestral lands. Tension exploded between the local government and residents.

The community – spurred in part by Marquez and Carabali – geared into action; residents called community meetings, marched on the town, and set up road blocks. As a result, the eviction order was suspended multiple times, and in December 2010, La Toma officially won their case with Colombia’s Constitutional Court. Hector Sarria’s mining license as well as up to 30 other illegal mining permits were suspended permanently. But, as disillusioned residents are quick to point out, the decision could change at any time.

“Wayuu Gold”

Much like the people of La Toma, the indigenous Wayuu people who make their home in northeast Colombia have also found themselves the target of paramilitary wrath. Wayuu ancestral land is rich in coal and salt, and their main port, Bahia Portete, is ideally situated for drug trafficking, making them an enticing target. In 2004, armed men ravaged the village for nearly 12 hours, killing 12, accounting for 30 disappearances, and displacing thousands. Even now, seven years later, those brave enough to lobby for peace face threats.

Now, other natural resource pressures have emerged. In 2011, growing towns nearby started siphoning water from Wayuu lands, and climate change is expected to exacerbate the situation. A 2007 IPCC report wrote that “under severe dry conditions, inappropriate agricultural practices (deforestation, soil erosion, and excessive use of agrochemicals) will deteriorate surface and groundwater quantity and quality,” particularly in the Magdalena river basin where the Wayuu live. Glacial melt will also stress water supplies in other parts of Colombia. The threat is very real for indigenous peoples like the Wayuu, who call water “Wayuu gold.”

“Without water, we have no future,” says Griselda Polanco, a Wayuu woman, in a video produced by UN Women.

The basic right to water has always been a contentious issue for indigenous peoples in Latin America – perhaps most famously in Cochabomba, Bolivia – and Colombia is no different: most recently 10,000 protestors took to the streets in Bogota to lobby for the right to water.

Post-Conflict Land Tenure Tensions

Perhaps the Wayuu and people of La Toma’s best hope is in a new Victims’ Law, ratified in June 2011, but in the short term, tensions look set to increase as Colombia works to implement it. The law will offer financial compensation to victims or surviving close relatives. It also aims to restore the rights of millions of people forced off their land, including many Afro-Colombian and indigenous peoples.

But “some armed groups – which still occupy much of the stolen land – have already tried to undermine the process,” reports the BBC. “There are fears that they will respond violently to attempts by the rightful owners or the state to repossess the land.”

Rhodri Williams of TerraNullius, a blog that focuses on housing, land, and property rights in conflict, disaster, and displacement contexts, wrote in an email to New Security Beat that there are many hurdles in the way of the law being successful, including ecological changes that have already occurred:Perhaps the biggest obstacle is the fact that many usurped indigenous and Afro-Colombian territories have been fundamentally transformed through mono-culture cultivation. Previously mixed ecosystems are now palm oil deserts and no one seems to have a sense of how restitution could meaningfully proceed under these circumstances. Compensation or alternative land are the most readily feasible options, but this flies in the face of the particular bond that indigenous peoples typically have with their own homeland. Such bonds are not only economic, in the sense that indigenous livelihoods may be adapted to the particular ecosystem they inhabit, but also spiritual, with land forming a significant element of collective identity. Colombia has recognized these links in their constitution, which sets out special protections for indigenous and Afro-Colombian groups, but has failed to apply these rules in practice. For many groups, it may now be too late.

As National Geographic explorer Wade Davis said at the Wilson Center in April, climate change can represent as much a psychological and spiritual problem for indigenous people as a technical problem. Unfortunately, as land-use issues such as those faced by Afro-Columbian communities, the Wayuu, and many other indigenous groups around the world demonstrate, there is a legal dimension to be overcome as well.

Sources: BBC News, Colombia Reports, International Displacement Monitoring Centre, PBS, Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, UN Women. The War We Are Living, part of the PBS series Women, War, and Peace, was instrumental to the framing of this piece.

Image and Video Credit: “Countryside Near Manizales, Colombia,” courtesy of flickr user philipbouchard; The War We Are Living video, courtesy of PBS. -

El Niño, Conflict, and Environmental Determinism: Assessing Climate’s Links to Instability

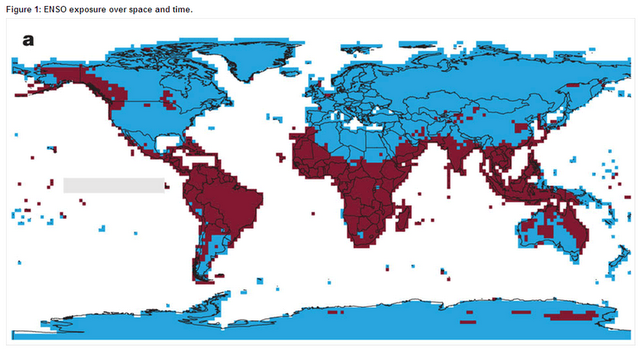

›October 5, 2011 // By Schuyler NullA recent Nature article on climate’s impact on conflict has generated controversy in the environmental security community for its bold conclusions about links between the global El Niño/La Niña cycle and the probability of intrastate conflict.

-

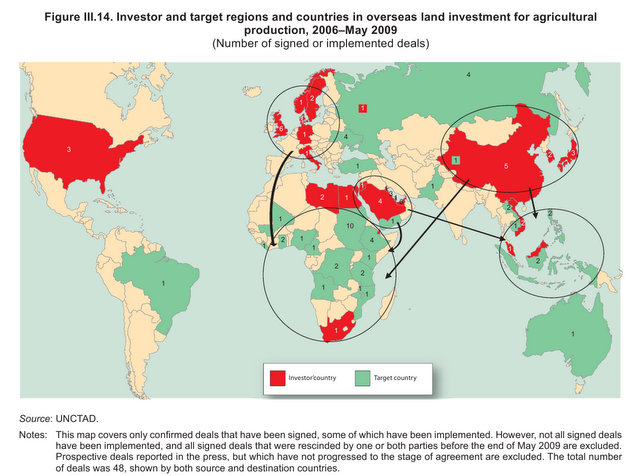

In Rush for Land, Is it All About Water?

›July 26, 2011 // By Christina DaggettOver the past few years, wealthy countries with shrinking stores of natural resources and relatively large populations (such as China, India, South Korea, and the Gulf states) have quietly purchased huge parcels of fertile farmland in Africa, South America, and South Asia to grow food for export to the parent country. With staple food prices shooting up and food security projected to worsen in the decades ahead, it is little wonder that countries are looking abroad to secure future resources. But the question arises: Are these “land grabs” really about the food — or, more accurately, are they “water grabs”?

The Great Water Grab

With growing urban populations, an expanding middle class, and increasingly scarce arable land resources, some governments and investors are snapping up the world’s farmland. Some observers, however, have pointed out that these dealmakers might be more interested in the water than the land.

In an article from The Economist in 2009, Peter Brabeck-Letmathe, the chairman of Nestlé, claimed that “the purchases weren’t about land, but water. For with the land comes the right to withdraw the water linked to it, in most countries essentially a freebie that increasingly could be the most valuable part of the deal.”

Consider some of the largest investors in foreign land: China has a history of severe droughts (and recently, increasingly poor water quality); the Gulf nations of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar, and Bahrain are among the world’s most water-stressed countries; and India’s groundwater stocks are rapidly depleting.

A recent report from the World Bank on global land deals highlighted the effect water scarcity is having on food production in China, South Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa, stating that “in contrast, Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America have large untapped water resources for agriculture.”

Keeping Engaged and Informed

“The water impacts of any investment in any land deal should be made explicit,” said Phil Woodhouse of the University of Manchester during the recent International Conference on Global Land Grabbing, as reported by the New Agriculturist. “Some kind of mechanism is needed to bring existing water users into an engagement on any deals done on water use.”

At the same conference, Shalmali Guttal of Focus on the Global South cautioned, “Those who are taking the land will also take the water resources, the forests, wetlands, all the wild indigenous plants and biodiversity. Many communities want investments but none of them sign up for losing their ecosystems.”

With demand for water expected to outstrip supply by 40 percent within the next 20 years, water as the primary motivation behind the rush for foreign farmland is a factor worth further exploration.

Global Farming

According to a report from the Oakland Institute, nearly 60 million hectares (ha) of African farmland – roughly the size of France – were purchased or leased in 2009. With these massive land deals come promises of jobs, technology, infrastructure, and increased tax revenue.

In 2008 South Korean industrial giant Daewoo Logistics negotiated one of the biggest African farmland deals with a 99-year lease on 1.3 million ha of farmland in Madagascar for palm oil and corn production. The deal amounted to nearly half of Madagascar’s arable land – an especially staggering figure given that nearly a third of Madagascar’s GDP comes from agriculture and more than 70 percent of its population lives below the poverty line. When details of the deal came to light, massive protests ensued and it was eventually scrapped after president Marc Ravalomanana was ousted from power in a 2009 coup.

While perhaps an extreme example, the Daewoo/Madagascar deal nonetheless demonstrates the conflict potential of these massive land deals, which are taking place in some of the poorest and hungriest countries in the world. In 2009, while Saudi Arabia was receiving its first shipment of rice grown on farmland it owned in Ethiopia, the World Food Program provided food aid to five million Ethiopians.

Other notable deals include China’s recent acquisition of 320,000 ha in Argentina for soybean and corn cultivation – a project which is expected to bring in $20 million in irrigation infrastructure, the Guardian reports – and a Saudi Arabian company which has plans to invest $2.5 billion and employ 10,000 people in Ethiopia by 2020, according to Gambella Star News.

But governments in search of cheap food aren’t the only ones interested in obtaining a piece of the world’s breadbasket: Individual investors are also heavily involved, and the Guardian reports that U.S. universities and European pension funds are buying and leasing land in Africa as well.

The Future of Land and Water

Whatever the benefits or pitfalls, large-scale land deals around the world look set to continue. The world is projected to have 7 billion mouths to feed by the end of this year and possibly 10 billion plus by the end of the century.

Currently, agriculture uses 11 percent of the world’s land surface and 70 percent of the world’s freshwater resources, according to UNESCO. If and when the going gets tough, how will the global agricultural system respond? Whose needs come first – the host countries’ or the investing nations’?

Christina Daggett is a program associate with the Population Institute and a former ECSP intern.

Photo Credit: Number of signed or implemented overseas land investment deals for agricultural production 2006-May 2009, courtesy of GRAIN and the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD).

Sources: BBC News, Canadian Water Network, Christian Science Monitor, Circle of Blue, The Economist, Gambella Star News, Guardian, Maplecroft, New Agriculturalist, Oakland Institute, State Department, Time, UNFPA, UNESCO, World Bank, World Food Program. -

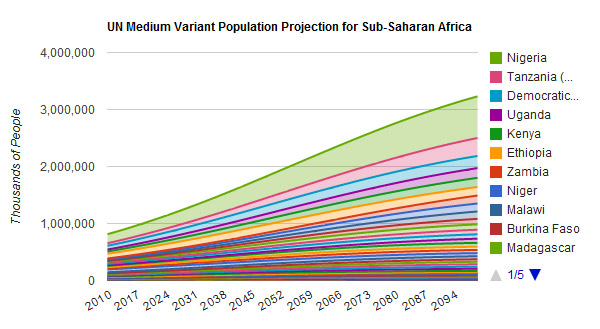

One in Three People Will Live in Sub-Saharan Africa in 2100, Says UN

›June 8, 2011 // By Schuyler NullBetween now and 2100, three out of every four people added to world population will live in sub-Saharan Africa. That’s what the medium variant of the UN’s world population projections estimates.* As we noted in our previous post on the latest UN numbers, Nigeria leads sub-Saharan growth, but other countries will also grow by major multiples: Tanzania and Somalia will be 7 times larger; Malawi more than 8 times; and Niger, to grow to more than 10 times its current population.

-

Accessing Maternal Health Care Services in Urban Slums: What Do We Know?

›“Addressing the needs of urban areas is critical for achievement of maternal health goals,” said John Townsend, vice president of the Reproductive Health Program at the Population Council. “Just because there is a greater density of health services does not mean that there is greater access.”

Townsend moderated a discussion on the challenges to improving access to quality maternal health care in urban slums as part of the 2011 Maternal Health Dialogue Series with speakers Anthony Kolb, urban health advisor at USAID; Catherine Kyobutungi, director of health systems and challenges at the African Population Health Research Center; and Luc de Bernis, senior advisor on maternal health at the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). [Video Below]

Mapping Urban Poverty

“Poverty is becoming more of an urban phenomenon every day,” said Kolb. With over 75 percent of the poor in Central Asia and almost half of the poor in Africa and Asia residing in cities and towns by 2020, “urban populations are very important to improving maternal health,” he added.

Collecting accurate data in informal settings such as slums can be very challenging, and there is often a “systematic undercounting of the urban poor,” said Kolb. Data often fails to capture wealth inequality in urban settings, and there is often a lack of attention to the significant variability of conditions between slums.

Kolb also warned about the risk of generalization: “Slums and poverty are not the same.” In practice, there is not a standardized definition of what constitutes a slum across countries, he said. “It is important to look at different countries and cities individually and understand how inequality is different between them.” Slum mapping can help to scope out challenges, allocate resources appropriately, and identify vulnerability patterns that can inform intervention design and approach, he said.

Maternal Health in Nairobi Slums

Addressing the maternal health needs of the nearly 60 percent of urban residents who live in slums or slum-like conditions will be a critical step to improving maternal health indicators of a rapidly urbanizing Kenya, said Kyobtungi.

Only 7.5 percent of women in Kenyan slums had their first antenatal care visit during their first trimester of pregnancy and only 54 percent had more than three antenatal care visits in all – rates significantly lower than those among urban women in non-slum settings.

“In some respects, [the urban poor] are doing better than rural communities, but in other ways they are behind,” said Kyobtungi. But, she said, there are many unique opportunities to improve maternal health in slums: “With these very high densities, you do have advantages; with very small investments, you can reach many more people”

Output-based voucher schemes – in which women pay a small fee for a voucher that entitles them to free, high-quality antenatal care, delivery services, and family planning – have been implemented to help poor, urban women access otherwise expensive services. But poor attitudes towards health care workers, transportation barriers, and high rates of crime still prevent some women from taking advantage of these vouchers, said Kyobtungi.

The majority of maternal health services in slums are provided by the private facilities, though size and quality vary widely. “There is a very high use of skilled attendants at delivery, but the definition of skilled is questionable,” said Kyobtungi

“Without supporting the private sector,” Kyobutungi said, “we cannot address the maternal health challenges within these informal settlements.” Combined with an improved supervision and regulation system, providing private maternal health facilities with training, equipment, and infrastructure could help to improve the quality of services in urban slums, she concluded.

Reducing Health Inequalities

“While we have evidence that health services, on average, may be better in urban areas than in rural areas, this often masks wide disparity within the population,” said de Bernis. “Reducing health inequities between and within countries is a matter of social justice.”

When it comes to family planning, total fertility rates are lower in cities, but “the unmet need…is still extremely important in urban areas,” explained de Bernis. Many poor women in cities, especially those who live in marginalized slum populations, do not have access to quality reproductive health services – a critical element to reducing maternal morbidity and mortality rates.

Economic growth alone, while important to help improve the health status of the poor in urban settings, will not solve these problems, said de Bernis. To reduce health disparities within countries, de Bernis advocated for “appropriate social policies to ensure reasonable fairness in the way benefits are distributed,” including incorporating health in urban planning and development, strengthening the role of primary health care in cities, and putting health equity higher on the agenda of local and national governments.

Event Resources:Source: African Population Research Center, United Nations Population Fund.

Photo Credit: “Work Bound,” courtesy of flickr user Meanest Indian (Meena Kadri). -

Tunisia Predicted: Demography and the Probability of Liberal Democracy in the Greater Middle East

›

In 2008, demographer Richard Cincotta predicted that between 2010 and 2020 the states along the northern rim of Africa – Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt – would each reach a demographically measurable point where the presence of at least one liberal democracy (and perhaps two), among the five, would not only be possible, but probable. Recent months have brought possible first steps to validate that prediction. [Video Below]

-

Tunisia’s Shot at Democracy: What Demographics and Recent History Tell Us

›January 25, 2011 // By Richard Cincotta

While events in Tunisia, beginning mid-December and leading ultimately to President Ben Ali’s departure within a month, have rocked the Arab world, they leave an open question: Will Tunisia’s “Jasmine Revolution” ultimately lead to the Arab world’s first liberal democracy? [Video Below]

-

India’s Maoists: South Asia’s “Other” Insurgency

›July 7, 2010 // By Schuyler Null

The Indian government’s battle with Maoist and tribal rebels – which affects 22 of India’s 35 states and territories, according to Foreign Policy and in 2009 killed more people than any year since 1971 – has been largely ignored in the West. That should change, as South Asia’s “other” insurgency, fomenting in the world’s largest democracy and a key U.S. partner, offers valuable lessons about the role of resource management and stable development in preventing conflict.

Showing posts from category featured.