Showing posts from category environment.

-

Global Climate Change Vulnerability and the Risk of Conflict

›In a study from the Center for Sustainable Development at Uppsala University in Sweden titled “Climate Change and the Risk of Violent Conflicts in Southern Africa,” authors Ashok Swain, Ranjula Bali Swain, Anders Themnér, and Florian Krampe examine the potential for climate change and variability to act as a “threat multiplier” in the Zambezi River Basin. The report argues that “socio-economic and political problems are disproportionately multiplied by climate change/variability.” A reliance on agriculture, poor governance, weak institutions, polarized social identities, and economic challenges in the region are issues that may combine with climate change to increase the potential for conflict. Specifically, the report concludes that the Matableleland-North Province in Zimbabwe and Zambezia Province in Mozambique are the areas in the region most likely to experience climate-induced conflicts in the near future.

The “Climate Vulnerability Monitor 2010: The State of the Climate Crisis,” published by Madrid-based DARA and the Climate Vulnerable Forum, is a comprehensive atlas of climate change vulnerability around the world. The report examines country vulnerability in four impact areas – health, weather disasters, habitat loss, and economic stress – and compares current levels of vulnerability with those expected in 2030. Of the 184 assessed countries, nearly all registered high vulnerability to at least one impact area. The report estimates that there are 350,000 “climate-related deaths” each year, almost 80 percent of which are children living in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Finally, the report features an overview of climate change basics, country profiles, and reviews on the effectiveness of several climate adaptation methods. -

Book Launch: ‘Human Population: Its Influence on Biological Diversity’

›Measurements of “human population density and growth can be used to identify changes in the viability of native species, and more directly, in changes in ecological systems or habitat quality,” said Richard Cincotta, consultant at the Environmental Change and Security Program and demographer-in-residence at the Stimson Center, speaking at the book launch of Human Population: Its Influence on Biological Diversity.

Cincotta was joined by coeditor L.J. Gorenflo, associate professor of landscape architecture at Penn State University, and contributing author Christopher Small, research professor at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and adjunct professor at Columbia University, to discuss the book’s objectives, its diverse and multidisciplinary contributors, and its policy implications. [Video Below]

Establishing a Handbook for the Field

“Human Population: Its Influence on Biological Diversity establishes a handbook for the field,” said Cincotta. While the scientific volume is specifically geared towards researchers and conservation managers rather than policymakers, “there are a few Washington-type policy messages that are useful,” he added.

Human population affects biological diversity in multiple ways. While population density alone can be strongly indicative of the viability of different populations of native species, human activities and their chemical and energetic byproducts can also have a strong impact, even when human population density is low, said Cincotta.

Conserving Biodiversity in Different Settings

“Planned solutions, based on strategic actions, increasingly are essential,” said Gorenflo, a professor at Penn State University. “The days of letting nature take care itself are probably gone.” Gorenflo presented results from the two chapters he worked on: “Human Demography and Conservation in the Apache Highlands Ecoregion, U.S.-Mexico Borderlands” and “Exploring the Association Between People and Deforestation in Madagascar.”

“Population density seems to be a reasonably good indicator of biodiversity loss,” said Gorenflo. Data from the Apache Highland Ecoregion (a 12 million-hectare area located along the U.S.-Mexico border) indicate that biodiversity tends to drop off at population densities of more than 10 people per square kilometer. Conservation efforts in areas within the ecoregion that are at, or close to, this density threshold will likely encounter challenges to maintaining biodiversity, he said.

Human mobility is a major consideration, said Gorenflo: “Whereas high fertility can create population growth over generations, high mobility can create population growth in a matter of months or years.” In the Apache Highlands, for example, the 40 percent increase in population between 1990 and 2000 was largely caused by migration into U.S. cities in the region.

In Madagascar, Gorenflo and colleagues examined whether population growth and poverty were systematically driving deforestation and loss of biodiversity. Using data from the 1990s, they found that higher population density only slightly raises rates of deforestation and large increases in income only modestly decrease deforestation.

Not surprisingly, they found that the likelihood of deforestation decreased dramatically in protected areas. In addition, proximity to roads or footpaths was associated with significantly higher rates of deforestation. “Roads, footpaths, and protected areas are all policy decisions,” Gorenflo pointed out. “So when bilateral or multilateral organizations decide to invest in development in a place like Madagascar, they can look at these sorts of investments as being important.”

While there are some similarities to be drawn between regions’ experience with population and biodiversity, said Gorenflo, “every locality likely has a slightly different story; you need to do context-specific studies to get a real handle on what is going on.”

The Human Habitat

In his chapter, “The Human Habitat,” Christopher Small of the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory said his goal was “to set the stage for some of the more detailed studies by taking a look at the global distribution of human population.”

Using census data and satellite-derived maps of night lights to serve as a “proxy for development,” Small found that “people are everywhere, but they are not evenly distributed.”

At least half the world’s population lives on less than three percent of the inhabitable land, and most people live at densities between 100 and 1000 people per square kilometer. At both local and global scales, population density and city size are dominated by extremes: There are large numbers of small groups of people, and small numbers of large groups of people, he said.

“The environments where people live are more strongly correlated with features of the landscape than they are with climatic parameters,” said Small. While humans have effectively adapted to a range of climates, the majority of people tend to cluster close to rivers, at low elevations, and close to coastlines. Although it was once thought that three-quarters of the world’s population lived in coastal regions, Small’s results show that the actual number is close to half of these previous assumptions.

Understanding the spatial and environmental distribution of population and managing population growth may therefore help minimize negative impacts on specific habitats and biomes, said Small.

Image Credit: “View from a Madagascar Train,” courtesy of flickr user cr01. -

Michael Kugelman, Dawn

Aquaculture’s Promise for Food-Insecure Pakistan

›June 7, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Michael Kugelman, appeared on Dawn.

“Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day,” the ancient Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu famously said. “Teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime.”

For years, this adage has helped frame debates across a variety of disciplines. However, while globally influential, it is by no means universally applicable – as the sad realities of Sindh make painfully clear. In this parched, food-insecure region flush with fishermen and farmers, people have long known how to fish. The problem is that with water bodies shriveling up, there are increasingly fewer fish to catch. Many impoverished residents would be grateful for a single fish, given their struggles to secure a day’s worth of food.

Pakistan’s natural resource constraints know no provincial borders, yet they are notably severe in Sindh. Water tables are plummeting, with great volumes of Indus River flows diverted upstream to satiate agricultural and urban demand in Punjab.

Sindh’s water security is further threatened by population growth and global warming, and by the water-intensive, large-scale farming envisioned by foreign investors jockeying for agricultural land.

With surface water supplies threatened, users are increasingly tapping groundwater resources – yet according to the Pakistan Council of Research in Water Resources, a staggering 95 percent of the province’s shallow groundwater supplies are bacteriologically contaminated. This is unsurprising, given the technical deficiencies and inefficiency that characterize Sindh’s water treatment facilities.

In a province where so many livelihoods are tied to water availability and food production, water stress aggravates food insecurity and threatens economic well-being. A recent World Bank report concludes that Pakistan’s poorest spend at least 70 percent of their meager incomes on food – and undoubtedly many of them hail from Sindh. According to data from the Pakistan Agricultural Research Council, some of the province’s small farmers spend a whopping 87 percent of their incomes on food.

Continue reading on Dawn.

Michael Kugelman is a program associate for the Asia Program at the Woodrow Wilson Center.

Photo Credit: A child stands amongst buildings destroyed by the floods in Sindh province, courtesy of flickr user DFID – UK Department for International Development. -

Measuring Ecosystem Vitality and Public Health With the Environmental Performance Index

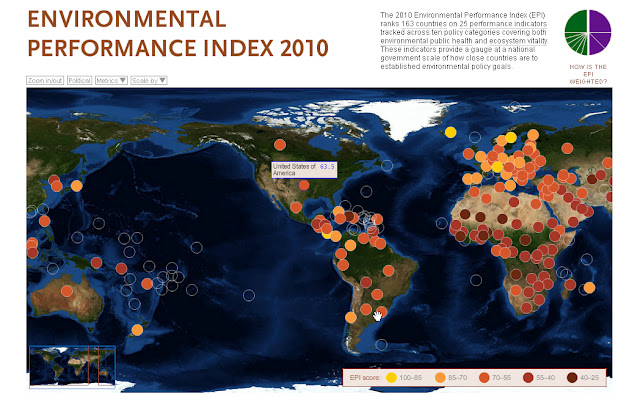

›The Environmental Performance Index (EPI) is a comparative analytic tool for policymakers created jointly by Yale and Columbia Universities in collaboration with the World Economic Forum and Joint Research Centre of the European Commission. The EPI was created in 2006 and is updated biannually. Data is drawn from 25 performance indicators that fall under 10 well-established policy categories, including the environmental burden of disease, the effects of water on human health, and agriculture. The indicators serve as a “gauge at a national government scale of how close countries are to established environmental [and health] policy goals,” write the authors.

The EPI draws data from a diverse array of sources, such as the World Health Organization, Food and Agriculture Organization, University of New Hampshire, and World Resources Institute. Users can view visualizations of the compiled data via an interactive map and the data is also available in the form of rankings charts, individual country profiles, and country group comparisons. The interactive map also allows users to isolate performance indicators or policy categories in order to compare an individual country’s performance with global trends. Furthermore, indicators may be scaled to visually reflect a country’s performance in relation to drivers of environmental performance, like gross domestic product, level of corruption, and government effectiveness.

This tool is particularly useful because users can effectively leverage points for policy change by identifying linkages between environmental policy and other issue areas, such as public health or sanitation. The EPI enables policymakers to visually conceptualize problematic regions, optimize investments in environmental protection, and identify best practices.

The index’s greatest weakness is its inability to track changes in performance over time. A pilot project was launched last year that tracks whether a country has progressed or deteriorated in an area of environmental performance, but the authors note that the project has “raised more questions than answers,” particularly concerning data availability and interpretation. Additionally, there are gaps in the data. Although these gaps signify a data quality weakness, they also support the continued calls for increased data collection by governments and other organizations to better inform environmental decision-making. -

Yemen Beyond the Headlines: Losing the Battle to Balance Water Supply and Population Growth

›Part three of the “Yemen Beyond the Headlines: Population, Health, Natural Resources, and Institutions” event, held at the Wilson Center on May 18.

Overlooked in most news coverage of Yemen’s crisis is the country’s struggle to manage its limited natural resources – particularly its rapidly depleting groundwater – in the face of soaring population growth. At the recent Wilson Center event, “Yemen: Beyond the Headlines,” Yemen’s ambassador to Germany, Mohammed Al-Eryani, and Daniel Egel of the RAND Corporation outlined Yemen’s shaky prospects for economic development without more sustainable agricultural practices and more efficient water management. [Video Below]

With a population of more than 24 million and a total fertility rate (TFR) of 5.5 – nearly double the average TFR for the region – Yemen’s population is projected to grow to 36.7 million by 2025 and jump further to 61.6 million by mid-century, according to the latest UN projections. While those figures may not seem large by global standards, given Yemen’s already limited stocks of arable land and groundwater, the country’s rapid rate of growth may quickly outpace its resources.

“Already in a Crisis”: The Groundwater Deficit

Yemen’s per capita water supply is falling fast in the face of booming population growth and agricultural consumption, said Al-Eryani, a water engineer who founded Yemen’s Ministry of Water and the Environment. While the commonly accepted threshold for water scarcity is 1700 cubic meters or less per capita, Yemen’s per capita renewable water availability is now in the neighborhood of 120 cubic meters, he said.

Meanwhile, water scarcity has been exacerbated by erratic precipitation that has hit rainfall-dependent farmers especially hard. In a country with no real rivers or perennial streams, rainfall harvesting has long enabled agricultural production, as evidenced by the country’s many intricately terraced hillsides – “the food baskets of Yemen,” said Al-Eryani.

Yemenis have coped with shifting precipitation patterns by drawing more groundwater for irrigation and other domestic uses. While drilling wells has provided some short-term relief, the practice is unsustainable in the long term, creating a “water deficit,” Al-Eryani said, that continues to grow each year.

In the populous Sanaa basin, home to the Yemeni capital, consumption outweighs the aquifer’s natural rate of recharge by a factor of five to one and groundwater levels have been plummeting at six meters per year, he said. With only minimal government regulation of drilling, the country’s groundwater situation is poised to worsen, one of the reasons Al-Eryani declared his country is “already in a crisis.”

Stalled Economic Development

Yemen’s stalled economic development is particularly pronounced outside of urban areas, “where the resources are,” said Daniel Egel, citing the country’s failure to build modern transportation infrastructure and develop other economic activities besides farming. He called for the international development community to focus on creating jobs in rural areas, particularly by increasing the financing available for non-agricultural businesses and by improving secondary roads. In addition, he warned development actors to be aware of how gender inequality and local social structures, such as tribes, affect development efforts.

Given the country’s dependence on agriculture, water scarcity poses a threat to Yemen’s food security and its economic development. Three out of every four Yemeni villages depend on rainfall for irrigation, Egel said, making them highly vulnerable to unexpected climate change-induced shifts in precipitation patterns. Water scarcity also weakens the financial stability of Yemeni households, with the cost of water “accounting for about 10 percent of income during the dry season,” he said.

Averting a “Domino Effect”

Al-Eryani asserted that water management policies will “have to be designed in piecemeal fashion,” as no one single action will avert a catastrophe. He suggested a number of steps to alleviate the country’s growing water crunch, including:- Focus on the rural population, which makes up 70 percent of the population, has the highest fertility rates, and are the most reliant on agriculture;

- Move development efforts outside of Sanaa to other regions of the country;

- Increase investment in desalination technology for coastal areas;

- Increase water conservation in the agricultural sector; and,

- Exploit fossil groundwater aquifers in Yemen’s sparsely populated eastern reaches.

“The battle to strike a sustainable balance between population growth and sustainable water supplies was lost many years ago,” Al-Eryani said. “But maybe we can still win the war if we can undertake some of these measures.”

See parts one and two of “Yemen Beyond the Headlines: Population, Health, Natural Resources, and Institutions” for more from this Wilson Center event.

Sources: UN Population Division, World Bank.

Photo Credit: “At the fountain,” courtesy of flickr user Alexbip. -

Watch: Janani Vivekananda on Climate Change and Stability in Fragile States

›At International Alert, the starting point for thinking about how climate change affects stability is recognizing that climate change will interact with and amplify existing social, economic, and political stressors in fragile communities, said Janani Vivekananda in this interview with the ECSP.

“Rather than climate change being this single, direct causal factor which will spark conflict at the national level,” Vivekananda said, these stressors “will shift the tipping point at which conflict might ignite.” In places that are already weakened by instability and conflict, climate change will simply be an additional challenge.

To address this additional challenge, Vivekananda said two things must be understood about the effects of climate change on fragile states: 1) Environmental, social, economic, and political stressors will be most evident at the household and community level; and 2) Those stressors are interrelated.

“You can’t address one of these things in isolation from the others. You have to understand how they all interact together to be able to respond appropriately,” she said. “We can’t think about food security, for example, without thinking about land degradation.” In addition, responses need to be relevant to their context, and that context “can only be understood through very sub-national, context-specific evidence.” Vivekanada explained that this kind of evidence can only come from a “bottom-up” approach, which should be coordinated as part of a broader effort.

For more on the connections between climate change and stability, see The New Security Beat’s summary of “Connections Between Climate and Stability: Lessons From Asia and Africa,” with Janani Vivekanada, Jeffrey Stark of the Foundation for Environmental Security and Sustainability, and Cynthia Brady of USAID speaking at the Woodrow Wilson Center on May 10. -

Annie Murphy, International Reporting Project

Mozambique Coal Mine Brings Jobs, Concerns

›May 31, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Annie Murphy appeared on the International Reporting Project and NPR (follow the links for the accompanying audio track as well). Murphy appeared with three other IRP fellows at the Wilson Center on April 28 to talk about their experiences reporting abroad.

As developing countries grow, their need for raw materials grows, too.

This is the case for Brazil, a country that has much in common with the nation of Mozambique: Both have a mix of African and Portuguese influences; both are rich in natural resources; and both fought long and hard to throw off European colonialism.

Today, however, a Brazilian coal mine in Mozambique has some wondering what the energy demands of growing economies like Brazil really mean for African countries like Mozambique.

This coal mine in northwestern Mozambique is owned by the Brazilian company Vale — it’s a gaping, dark gray pit in the middle of a green, windswept savannah. Still under construction, it currently employees about 7,500 people.

Jose Manuel Guilengue, 23, a machine operator, says that he and a friend traveled 1,000 miles from the capital to get there, where they were both hired. That was a year ago. He now makes around $400 a month — which is more than four times the average salary in Mozambique.

According to the general manager overseeing construction, Osvaldo Adachi, this mine will produce about 11 million tons of coal each year, for at least three decades.

Continue reading and listen to the audio at the International Reporting Project.

Annie Murphy reported this story during a fellowship with the International Reporting Project (IRP). To hear more about Murphy and the IRP program, see the event summary for “Reporting on Global Health: A Conversation With the International Reporting Project Fellows.”

Photo Credit: Adapted from Mozambique, courtesy of flickr user F H Mira. -

Elizabeth C. Economy, Council on Foreign Relations

The Truth About the Three Gorges Dam

›May 26, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Elizabeth C. Economy, appeared on the Council on Foreign Relations’ Asia Unbound blog.

It has only taken 90 years, but China’s leaders have finally admitted that the Three Gorges Dam is a disaster. With Wen Jiabao at the helm, the State Council noted last week that there were “urgent problems” concerning the relocation effort, the environment and disaster prevention that would now require an infusion of US$23 billion on top of the $45 billion spent already.

Despite high-level support for the project since Sun Yat-sen first proposed it in 1919, the dam has had serious critics within China all along. One of China’s earliest and most renowned environmental activists, Dai Qing, published the book Yangtze! Yangtze! in 1989, which explored the engineering and social costs of the proposed dam. The book was a hit among Tiananmen Square protestors, and Dai spent a year in prison for her truth-telling. In 1992, when the dam came up for a vote in the National People’s Congress, an unprecedented one-third of the delegates voted against the plan.

Once the construction began in 1994, the problems mounted. The forced relocation of 1.4 million Chinese was plagued with corruption; former Premier Zhu Rongji accused the construction companies of shoddy engineering, and little of the pollution control measures that were planned were actually taken. Water pollution skyrocketed in the reservoir. As Chinese officials acknowledged a few years back, “The Three Gorges Dam project has caused an array of ecological ills, including more frequent landslides and pollution, and if preventive measures are not taken, there could be an environmental catastrophe.”

It would be easy to argue that the State Council’s admission was too little too late. However, the new transparency matters for at least two reasons. First, it plays into the hands of environmentalists who have been arguing against Beijing’s aggressive plans for additional large-scale hydropower plants. Premier Wen, who has tried to slow the approval process for dams over the past several years, now has a bit more ammunition. Second, any acknowledgement by the Party that mistakes have been made is an important step toward the public’s right to question future policies. Let’s hope that more such transparency is on the way.

Elizabeth C. Economy is the C.V. Starr Senior Fellow and director for Asia Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations.

Photo Credit: Adapted from “Construction of the Three Gorges Dam,” courtesy of flickr user Harald Groven.