Showing posts from category environment.

-

Youth Need More Information on Climate, Population Links

›December 9, 2011 // By Brenda ZuluYouth need more information about climate change, but also on its links to reproductive health and gender, said Esther Agbarakwe, technical advisor for the Africa Youth Initiative on Climate Change. Speaking at the joint Aspen Institute, Population Action International, and Wilson Center side event, “Healthy Women, Healthy Planet,” at the COP-17 climate conference, Agbarakwe pointed out that “there are critical issues, like demography, the number of young people, and young women in this population, that should be discussed.” But, she said, they would likely not be brought up in any official manner at the conference because of fears about “population control.”

In Nigeria, young people, and particularly young girls, are frequently excluded from formal discussions about climate change and sustainable development. Growing up, Agbarakwe said she was aware of environmental change due to pollution in the Niger Delta, but her parents did not talk to her about reproductive health. In her community, many young girls had unplanned pregnancies and boys dropped out of school. It was only through a child rights activists’ club that she learned about how she could protect herself.

“That is why there is need to have young women in this discussion,” she said.

Giving a Voice to the Most Affected

Wendy Mnyandu, a student from Durban’s Zwelibanzi High School attending the side event, noted in an interview that climate changes have affected mothers more because they are dependent on the forest for energy.

“It is important for villagers to adapt to new technologies [such as] cook stoves, where they can use less fuelwood that will not take away the forest,” she said.

At the Wilson Center earlier this year, Agbarakwe explained how insufficient rain has led to longer trips to collect water, increasing women’s vulnerability. A friend of hers was raped while walking to the next village to fetch water after her own community’s well dried up – an ordeal that was not only emotionally and physically traumatizing, but also isolated her from her community and jeopardized her future plans and dreams.

“It is important for more men to talk about this topic,” said Roger-Mark De Souza, vice president of research at Population Action international, who also spoke at the side event. “I am talking on behalf of my mother, my daughters, my wife, and my granddaughters, for their voices are not often heard. I am a father of two young teenage boys and they know how to talk about this. By talking about it, we can see how family planning is very effective,” he said.

Talking About Population to Climate Experts, and Vice Versa

“Just last week I was in Dakar, Senegal, at the International Conference on Family Planning,” said De Souza. “I was talking to specialists and I was getting them interested in climate change.” Similarly, “more and more we find that climate change activists and specialists are appreciating that climate change is important to women and their wellbeing,” he said.

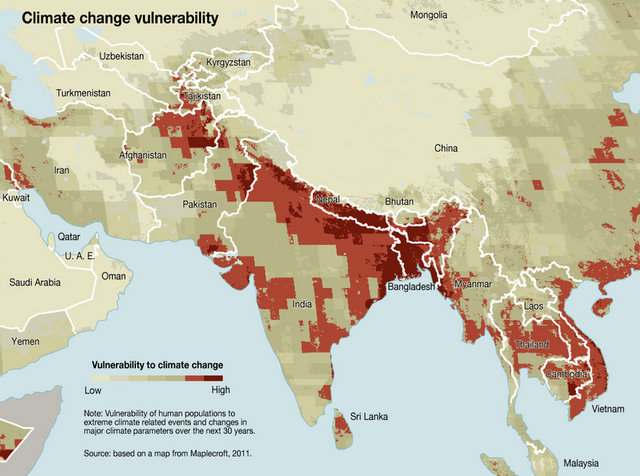

Population Action International (PAI) has mapped agricultural production, water stress, and increased vulnerability to climate change. “We see that there are 26 global hotspots where these issues are critical. What we have also done is look at these hotspots to determine where there is a very high unmet need for family planning,” said De Souza. PAI is using these maps to show the climate change community that a cost-effective investment in family planning could increase resilience in these areas.

De Souza said that in order to build support for programs that address these issues, it is important to look at national adaptation programs of action and their funding needs. “Funding is critical, and these types of interventions produce results – we need to understand where those missed opportunities are and tell that story to our policymakers and our delegations that are here in Durban and to keep with that message when we go back home,” he said.

Empowering Young African Women

Agbarakwe became interested in these issues after meeting former president of Ireland Mary Robinson, who also spoke at the side event. “I had met a Nigerian young man who challenged me that it was difficult for a woman to realize her career dreams because one day she will have to be married and bear children,” said Agbarakwe:When I saw my passion, I was confused and asked questions of Robinson on what she would do if she found herself at the crossroads like me. She told me as a young woman, I will find myself at a crossroad. That is why I am very determined about this issue, and that is what is needed, because when young women are empowered they actually can make decisions.

Robinson, the chair of the Global Leaders Council for Reproductive Health, said in an interview that she was heartened to see the number of youth at the side event. In Durban, she spoke with a group of young women who were part of Oxfam’s Project Empower:We met young women and several of them had come from the Eastern Cape [of South Africa]. They had come to Durban to look for work. Instead they found themselves in rural poverty. They had dreams of a better life for themselves, but their daily reality they talked to us about was nobody’s dream. They talked to us about negative impacts of their communities – the violence against women that is very prevalent, the unplanned pregnancies, and the reality of women who even have to use their bodies to gain money.

African women are looking for contraceptives, such as the female condom, where they can be in control, said Robinson; there are about 215 million women in the world who do not want to get pregnant but are not using modern contraception. “If we were to solve that problem, women [would not only] be better mothers, but also be better leaders in their communities,” she said.

The good thing was that they were ready to talk about the problems and did not consider themselves to be victims. They were strong women. They had learned to say ‘no’ and to say ‘respect me.’ They talked about going into some of the clinics and facing encounters with the police and that the police did not respect them. ‘We do not accept that anymore. We know now that we are members of the community who wish to be respected,’ they explained.

Brenda Zulu is a member of Women’s Edition for Population Reference Bureau and a freelance writer based in Zambia. Her reporting from the COP-17 meeting in Durban (see the “From Durban” series on New Security Beat) is part of a joint effort by the Aspen Institute, Population Action International, and the Wilson Center.

Sources: Population Action International, World Health Organization.

Photo Credit: “Viet Nam and Primary Education,” courtesy of flickr user United Nations Photo; video courtesy of Population Action International. -

Jason Bremner, Behind the Numbers

PHE Champions Bring Their Experiences From the Field to the International Family Planning Conference in Senegal

›December 8, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Jason Bremner, appeared on the Population Reference Bureau’s Behind the Numbers blog.

This past week at the 2011 International Conference on Family Planning, four practitioners from the field traveled from remote parts of the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Madagascar, and Tanzania to Dakar, Senegal, to share their successes and challenges in reaching remote communities with an integrated package of health, livelihood, and environment services. Together they made up the panel, “Reaching the Hardly Reached: Delivering Family Planning Through Population, Health, and Environment Integration.”

The panelists came from four environmental organizations whose starting point for working in these remote places was the protection of the biodiversity and natural resources upon which all life depends. Dr. Vik Mohan, physician and medical director for Blue Ventures, talked about how he and his organization transitioned from focusing initially on the conservation of coastal marine reserves and coral reefs to now working to improve health care, including access to family planning.

Blue Ventures, in response to community and women’s needs, opened a family planning clinic, and on the opening day, 20 percent of the women of reproductive age in the community came out to request contraceptives. Today they offer a whole spectrum of short- and long-acting contraceptive methods through partnerships with Marie Stopes International, Population Services International, and various funders. Blue Ventures reported that contraceptive prevalence had risen from 8 percent when they began in 2007 to 35 percent today.

Continue reading on Behind the Numbers.

Photo used with permission courtesy of PRB. Left to right: Didier Mazongo, WWF; Vik Mohan, Blue Ventures; Baraka Kalangahe, Tanzania Coastal Management Partnership; and Jason Bremner, PRB. -

New UNEP Climate Report Says Women Face “Disproportionately High Risks”

›December 8, 2011 // By Brenda ZuluA new United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) report, Women at the Frontline of Climate Change: Gender Risks and Hopes, released at COP-17, says that women, particularly those living in mountainous regions in developing countries, “face disproportionately high risks to their livelihoods and health from climate change, as well as associated risks such as human trafficking.”

Droughts, floods, and mudslides are affecting a growing number of people worldwide, in part because of climate change, but also because population growth is highest in some of the most vulnerable areas of the world. For example, in the 10 years from 1998-2008, floods affected one billion people in Asia, but only four million people in Europe.

According to UNEP, women often bear the brunt of such disasters: “In parts of Asia and Africa, where the majority of the agricultural workforce are female, the impacts of such disasters have a major impact on women’s income, food security, and health,” as they are responsible for about 65 percent of household food production in Asia and 75 percent in Africa. In addition, they are often more likely than men to lose their lives during natural disasters.

UNEP Executive Director Achim Steiner said in a press release that “women often play a stronger role than men in the management of ecosystem services and food security. Hence, sustainable adaptation must focus on gender and the role of women if it is to become successful.”

“Women’s voices, responsibilities, and knowledge on the environment and the challenges they face will need to be made a central part of governments’ adaptive responses to a rapidly changing climate,” he added.

Investing in low-carbon, resource-efficient green technologies, water harvesting, and alternatives to firewood could strengthen climate change adaptation and improve women’s livelihoods, says UNEP.

“If Insufficient, Family Planning Funds Should Be Scaled Up”

UNEP spokesperson Nick Nuttall said in an interview that there are wide differences between how people consume natural resources, with North Americans and Europeans consuming far more than someone in a developing country. We should move toward more efficient use of natural resources, make the transition to a low-carbon economy, and scale up renewable energies, which can reduce demand for fossil fuels to meet economic growth and population increases, he said.

Asked whether climate change funds should therefore support family planning, Nuttall said the UN supports the right of couples and women to choose the size of their families and that many UN agencies and NGOs provide that support already.

But, he said, “there are funds available for family planning and, if insufficient, they should be scaled up to meet the demands and requests of developing countries. Given that this is an issue far wider than climate change, these existing funding streams should be where the financial support comes, rather than from a climate fund.”

Brenda Zulu is a member of Women’s Edition for Population Reference Bureau and a freelance writer based in Zambia. Her reporting from the COP-17 meeting in Durban (see the “From Durban” series on New Security Beat) is part of a joint effort by the Aspen Institute, Population Action International, and the Wilson Center.

Sources: UNEP.

Image Credit: “Climate change vulnerability,” courtesy of Riccardo Pravettoni, UNEP/GRID-Arendal. -

Watch ‘Mother Jones’’ Kate Sheppard on Covering the Evolving Environment and Reproductive Rights Beat

› “My author bio says I cover energy, environment, and reproductive rights,” said Kate Sheppard of Mother Jones in an interview with ECSP. “One of the biggest challenges in covering that beat is even just articulating what that means.”

“My author bio says I cover energy, environment, and reproductive rights,” said Kate Sheppard of Mother Jones in an interview with ECSP. “One of the biggest challenges in covering that beat is even just articulating what that means.”

Fundamentally, Sheppard said she is interested in covering how policy decisions shape the future, which involves examining the intersections between these key issues. She spoke at a November 1 Wilson Center event on the challenges of reporting on population and environment, especially this year, when a great deal of media covered the world population reaching seven billion.

Sheppard is currently reporting on adaptation to climate change, looking at how human societies are responding to the changes that they are already experiencing, whether it be changes in migration patterns, resource availability, or food security. “I’m seeing this as a really ripe area where these things intersect, when we are talking about just how many people we are going to have in the future, and where they are going to be, and whether we can meet their needs in a society that is constantly changing,” she said.

Energy is another important area of intersection, said Sheppard. Access to energy is critical to ensuring a better future for the world’s inhabitants, but policy decisions must also take into account the fact that our fossil fuel resources are finite, she said. “We need to start thinking about ways we are going to do this sustainably for the world population in the future.” -

African Women, Most Vulnerable to Climate Change, Are Agents of Change

›December 6, 2011 // By Brenda ZuluIt is the poorest people whose lives are most undermined by changes in the weather, said Chair of the Global Leaders Council for Reproductive Health Mary Robinson at a side event on “Healthy Women, Healthy Planet” during COP-17 in Durban, South Africa. “When farmers don’t know how to predict the seasons, when there is more flooding than there was, when there are longer periods of drought and then flash flooding,” she said, people need more resilience. “They have to be even stronger in being able to cope with the drought and flooding.”From Population Action International’s Weathering Change – Fatima’s Story.

“In the past, February and March were planting months, while June and July were harvest months in the first season,” explained Constance Okollet, chairperson of the Osukura United Women Network in eastern Uganda, in an interview. “The second season started in August and September as planting months, but now we don’t have any seasons anymore.”

Okollet said that since 2007, there have been floods in her area that have destroyed homes and fields and forced some to leave their homes. “I actually had to leave when the floods destroyed my house and when I went back there was nothing; and immediately after that there was a drought after planting,” she said.

“These days we gamble with agriculture, as we are not sure when to plant. What we see now is, if it is not torrential rains, then it is a storm. During the rainy season, you find a lot of winds. We never used to see them and now we have mudslides, which are occurring every year. With heavy rains it has been difficult for people to dry cassava and groundnuts. Last month, I lost two fields of groundnuts because the rain has been very heavy,” Okollet said. “In the community, we used to harvest heavily, but it is not the same anymore.”

African women are often particularly vulnerable to such environmental disruptions. Okollet pointed out that women walk long distances to look for water and feed children before they go to school. “Women always eat little and leave the rest for their children,” she said. “Children are sick and there is a lot of death in the village because of hunger and lack of food security.”

Water-borne diseases, such as cholera, erupt after floods contaminate the water, and getting health care can be difficult for women because the health center is very far away.

Okollet said that when all this was happening, she and her fellow network members thought that maybe God was punishing them. “We only knew what was happening when Oxfam talked to us about climate change,” she said.

The Osukura United Women Network has asked the Ugandan government for help supplying early-maturing crops that will adapt to the seasonal change. The group is working to sensitize their community to the importance of hygiene and sanitation as well as working with men in the community to build wells and latrines.

“We need women to be agents of change in their local communities,” said Robinson.

Brenda Zulu is a member of Women’s Edition for Population Reference Bureau and a freelance writer based in Zambia. Her reporting from the COP-17 meeting in Durban (see the “From Durban” series on New Security Beat) is part of a joint effort by the Aspen Institute, Population Action International, and the Wilson Center.

Video Credit: “Fatima’s Story – Weathering Change Extra,” courtesy of vimeo user Population Action International. -

Susanna Murley for The Huffington Post

Compromise Is Hard: The Problems and Promise of REDD+

›December 6, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Susanna Murley, appeared on The Huffington Post.

In Durban this week delegates from around the world are examining the options to mitigate carbon emissions. What looks like the best chance for progress? REDD+ (for Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation, plus co-benefits – like conservation, sustainable management of forests, and enhancement of forest carbon stocks). REDD+ has been seen as a potentially powerful solution to solve both poverty and deforestation – in one fell swoop.

How does it work? Essentially, these programs would be funded by developed nations to help pay for community forestry projects in developing countries, if the communities can demonstrate – with verifiable data – that their efforts are saving forests that would have been destroyed or if they are planting trees that would permanently sequester carbon.

Will this work? Many other systems have tried and failed to reduce deforestation. In Indonesia, where an area of forest about the size of Nevada has been destroyed since 1990, activists have participated in demonstrations, legal actions, blockades and destruction of property to protest timber production. Many international NGOs have joined them in their campaigns against the forestry practices in Indonesia, releasing report after report on the “State of the Forest.” The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund have attempted to regulate forestry as conditions of their loans. None of it worked, and Indonesia continues to see massive amounts of illegal logging and deforestation.

Continue reading on The Huffington Post.

Sources: Center for International Forestry Research, Gellert (2010), MongaBay.com

Photo Credit: “Oil palm plantation,” courtesy of flickr user CIFOR (Ryan Woo). -

New Population, Health, and Environment Program for Lake Victoria

›With some of Africa’s highest population densities, ethnic diversity, and biodiversity, the Great Lakes region is one of the most volatile intersections of human development and the environment. A new population, health, and environment (PHE) initiative from Pathfinder International, announced Monday at the International Conference on Family Planning in Senegal, aims to help address these issues by supporting sustainable resource management and women’s right to choose when and how often they have children.

Jointly funded by the David and Lucile Packard Foundation and the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, with additional support from USAID’s Office of Population and Reproductive Health, the project will focus on Ugandan and Kenyan sections of the Lake Victoria basin.

Lake Victoria is the second largest freshwater source in the world, a biodiversity hotspot, and an important regional waterway, but regional population growth among the highest in Africa and economic development have led to declining water quality, reduced fish stocks, and industrial pollution. The basin as a whole supports upwards of 35 million people.

“This new project is a welcome development for many reasons,” said ECSP Director Geoff Dabelko. “It brings the integrated PHE approach to one of the world’s greatest lakes, it enables respected health NGO Pathfinder to pursue PHE efforts, and marks the return of a leading private donor, the MacArthur Foundation, to a group of foundations willing to support this innovative approach.”

Sono Aibe, senior advisor for strategic initiatives at Pathfinder emphasized the integrated challenges facing the region. “In these remote, resource dependent areas of the world, the interconnectedness between the health of people and the health of the environment is undeniable,” she said in a press release. “When women are empowered to participate in the sustainable management of natural resources alongside men and youth, as well as have access to sexual and reproductive health care services, their lives will improve and so will the condition of the ecosystems that they depend on.”

The project’s objective, according to Pathfinder, is to reduce threats to biodiversity, conservation, and ecosystem degradation by increasing access to family planning and sexual/reproductive health services. The project plans to develop scalable approaches that can be adopted by communities, local governments, and national governments. Technical support is to be provided by the BALANCED Project, ExpandNet, and the Population Reference Bureau.

“Lessons learned from this new project will help us better develop and design projects for vulnerable communities in fragile ecosystems, while simultaneously advocating for increased government support for integrated programs throughout the Lake Victoria Basin,” said Lucy Shillingi, Pathfinder’s country representative for Uganda.

The Lake Victoria effort will build upon the experiences of other integrated PHE efforts in the region, such as Rwanda’s SPREAD Project, Uganda’s Conservation Through Public Health, and Tanzania’s TACARE and Coastal Management Partnership.

Sources: Lake Victoria Basin Commission, Pathfinder International, UNEP. -

Jeanne Nyirakamana, PHE Champion

Reaching Rural Rwandans With Integrated Health and Livelihood Messages

›This PHE Champion profile was produced by the BALANCED Project.

Rwanda is one of the most densely populated countries on the planet, with more than 11 million people in one of Africa’s smallest countries, most of whom depend on the land as subsistence farmers. The country has diverse mountain, lake, and savannah landscapes, and the Virunga Mountain chain in the northwest part of the country is home to one-third of the world’s threatened mountain gorilla population. At the same time, the population throughout the country suffers from high rates of unmet need for contraception, and three percent of the adult population lives with HIV/AIDS. In a land under such intense pressure on natural resources, rural livelihood initiatives are critical to ensuring people have options for meeting their daily health and well-being needs.

For the past three years, Jeanne Nyirakamana has served as head of the health program for the Sustaining Partnerships to Enhance Rural Enterprise and Agribusiness Development (SPREAD) Project. Supported by the U.S. Agency for International Development through Texas A&M; University, the SPREAD Project is integrating a dynamic coffee production and quality improvement program in Rwanda with health outreach to improve community well-being. The health component works to improve the lives of coffee farmers and cooperative members by providing them with health information and services related to family planning, maternal and child health, prevention of sexually-transmitted infections (including HIV), and water and sanitation.

Training Peer Educators

Working closely with the coffee program, Nyirakamana’s team has trained more than 540 men, women, and youth peer educators who have reached more than 95,000 coffee farmers with education and services. Key communication messages highlight the links between sound decision-making and health-seeking behaviors, productive farms and agribusinesses, and strong and healthy families.

The program also leverages and supports local health resources through referrals to existing public health services, organization of mobile clinics, and community-based distribution of a socially marketed water purification solution (Sur Eau) and condoms (Prudence). According to Nyirakamana, one of the project’s greatest successes is the increased acceptance of family planning by farmers and their families and the more than 7,500 farmers who have been tested for HIV. In order to draw in as many coffee farmers as possible, many of the health and livelihood activities take place at the stations where the coffee beans are washed, at other buildings used by the coffee farmer cooperative, or during combined community meetings or home visits. At the washing stations, Nyirakamana’s team supports local health center staff to provide voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) and de-worming services while at the same time SPREAD-trained peer educators and coffee/health extension agents disseminate family planning information.

The cooperatives’ buildings have clean water, hand-washing stations, and small kiosks where condoms and Sur Eau are sold. These community health agents work with SPREAD to ensure that the greater community, not just the coffee farmers, has access to health knowledge and services. They learn how to teach the community about a range of health issues and each month they submit reports showing how many people they reached and with what kinds of messages. They are also becoming increasingly engaged in coffee and agribusiness activities. Through the success of their health activities, these agents are seen as vital community resources.

Integrated Results

By implementing this integrated population, health and environment (PHE) approach, the SPREAD Project staff is ensuring the health of the people and environment and success of the agribusiness. “You cannot care for the environment without first caring for the people who live and use that environment, so when you transmit dual messages [agriculture and health] you are able to hit two birds with one stone,” said Nyirakamana.

According to a 2010 evaluation of the project, farmers and their families reported improvements in personal and household hygiene; an increase in understanding and acceptance of family planning; uptake of HIV and VCT services; and use of condoms and other local health services. As well, they noted shifts in gender norms affecting household revenue use, alcohol, and reproductive health. The agribusiness stakeholders value the integrated approach as a means to more holistically meet farmers’ goals of increased incomes and improved lives and livelihoods.

This PHE Champion profile was produced by the BALANCED Project. A PDF version can be downloaded from the PHE Toolkit. PHE Champion profiles highlight people working on the ground to improve health and conservation in areas where biodiversity is critically endangered.

Photo Credit: BALANCED Project.