Showing posts from category economics.

-

Disease in the Developing World

Poverty, Politics, and Pollution

›November 15, 2010 // By Ramona GodboleA look at the most common illnesses that kill people in the developing world reveals, for the most part, easily preventable and/or treatable diseases and conditions, highlighting the deep disparities between health systems in rich and poor countries. But many of the causes and solutions to these common diseases are also linked to political and environmental factors as well as economic.

Cholera: “A disease of poverty”

Ten months after the earthquake that killed more than 230,000 people, Haiti is facing yet another disaster – a cholera outbreak. The current health crisis highlights broader structural and political issues that have plagued Haiti for years.

Cholera, an intestinal infection caused by bacteria-contaminated food or water, causes severe diarrhea and dehydration, but with quick and effective treatment, less than one percent of symptomatic people die according to the World Health Organization. According to BBC, as of November 15, more than 14,000 people have been hospitalized and over 900 deaths have been attributed to cholera in Haiti thus far.

Even before the earthquake, conditions in Haiti, the poorest country in the Western hemisphere, were bleak. The country has very high maternal and child mortality rates (again, highest in the Western hemisphere), and is in the midst of an ongoing environmental crisis, due to deforestation, soil loss, and flooding.

Less than 40 percent of the Haitian population has access to appropriate sanitation facilities and clean water is scarce, according to UNICEF. Displacement, rapid population growth, and destroyed infrastructure in the wake of the earthquake exacerbated already poor conditions and public health officials warned of the increased risk of cholera and other diarrheal diseases after the disaster.

Today these fears have become reality. While public health messages urging Haitians to wash their hands, boil drinking water, and use oral rehydration salts are working to control the current outbreak, long-term solutions to prevent future outbreaks will require much more systematic changes.

As Partners in Health Chief Medical Officer Joia Mukherjee puts it, cholera is “a disease of poverty.” Citing a joint report from Partners in Health and the Robert Kennedy Center for Human Rights, Mukherjee notes that in 2000, loans from the Inter-American Development Bank to improve water, sanitation, and health (including the public water supply in the Artibonite Valley, where the cholera outbreak originated) were blocked for political reasons by the U.S. government, in an effort to destabilize former President Aristide.

The failure of the international community to assist Haiti in developing a safe water supply, writes Mukherjee, has been a violation of the basic human right to water. To halt the current cholera epidemic and prevent future outbreaks, providing water security must become a priority in the reconstruction efforts of the international community.

Politics and Polio

Recent reports have indicated that the global incidence of polio, a highly infectious, crippling, and potentially fatal virus, is significantly declining and a new vaccine is renewing hopes of eradication. Nigeria, one of the few countries where polio continues to be endemic, has also made major progress over the last few years.

But the situation was very different just a few years ago. In 2003 religious and political leaders in Northern Nigeria banned federally sponsored polio immunization campaigns, citing “evidence” that the polio vaccine was contaminated with anti-fertility drugs intended to sterilize Nigerian women. The boycott led to an outbreak of the disease that spread to 20 countries and caused 80 percent of the world’s cases of polio during the length of the ban, according to a study in Health Affairs.

While the boycott was eventually stopped through the combined efforts of local, national, and pressure, the boycott serves as a useful reminder that global health problems can have political, rather than biological or behavioral, origins.

Combating Climate Change and Pneumonia

Studies from the World Health Organization indicate that exposure to unprocessed solid fuels increases pneumonia risk in children by a factor of 1.8, but today more than three billion people globally continue to depend on coal and biomass fuels for their cooking and heating needs.

Cooking and heating with these fuels creates levels of indoor air pollution that are up to 20 times higher than accepted WHO guidelines, putting people at considerable risk for lower respiratory infections. Women, who are often responsible for collecting fuel and performing household tasks like cooking, and their children, are particularly at risk. Today, exposure to indoor air pollution is responsible for 1.6 million deaths globally including more than 900,000 of the two million annual deaths from pneumonia in children under five years old, representing the most important cause of death in this age group.

A recent study from The Lancet shows improved cooking stoves could simultaneously reduce greenhouse gas emissions and the global burden of disease caused by indoor air pollution in developing countries. Such an intervention, the authors argue, could have substantial benefits for acute lower respiratory infection in children, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and ischemic heart disease. The potential health benefits don’t stop there: fuel-efficient stoves can also improve the security of women and children in conflict zones and decrease the risk of burns while improving local air quality.

There would be significant environmental benefits as well. A World Wildlife Fund project in Nepal, which provided loans to purchase biogas units and build improved cookstoves, curbed deforestation for firewood and grazing as well as reduced the incidence of severe cases of acute respiratory infection among under-five children.

Overall, greater access to modern cooking fuels and improved cooking stoves in the developing world could both mitigate climate change and make significant contributions to MDGs 4 & 5, which focus on the reduction of child and maternal mortality.

Prescription for Change

The international community’s experience with cholera in Haiti, polio in Nigeria, and pneumonia around the world shows that health issues in developing countries rarely occur in a vacuum. As these three cases demonstrate, politics, environmental, and structural issues, for better or worse, play an important role in health affairs in the developing world. Yet efforts to combat these conditions often focus only on prevention and treatment.

Antibiotics and vaccines alone cannot provide solutions to these problems. Employing economic, diplomatic and policy tools to address health and development challenges can save lives. More specifically, public health efforts should not only focus on poverty reduction, but also target environmental, political, and structural issues that contribute to disease globally.

Sources: BBC, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, CIA World Factbook, Health Affairs, The Lancet, Scientific American, UNICEF, United Nations, USAID, World Health Organization, and World Wildlife Fund.

Photo Credit: “Lining up for vaccination,” courtesy of flickr user hdptcar. -

Governing the Far North: Assessing Cooperation Between Arctic and Non-Arctic Nations

›November 12, 2010 // By Ken CristDespite fears of an unregulated race for Arctic territory and resources, there is currently considerable international cooperation occurring to address key issues in the Far North, said Betsy Baker of the Vermont Law School at an event hosted by the Canada Institute in collaboration with the Friedrich Ebert Foundation, the Kennan Institute, and the Environmental Change and Security Program. The program provided a timely forum to discuss efforts by Arctic and non-Arctic nations to cooperate on key environmental, security, and economic issues, and foster discussion on pressing Arctic governance questions. The event’s first panel was moderated by Don Newman, former senior parliamentary editor, CBC News.

Assessing Cooperation Among Arctic Nations

The United States, said Baker, is currently engaged in international cooperation in a number of areas including, shipping, emergency response and rescue, science, seabed mapping, and joint military exercises. The majority of U.S. Arctic initiatives are conducted via the Arctic Council, an institution that Secretary of State Hillary Clinton favors strengthening. Baker maintained that the most effective form of Arctic governance would be a “bottom up” approach. Governing structures closest to the end users, she explained, are the most effective means of ensuring economic development and environmental security.

Baker noted that the lack of infrastructure and search and rescue capabilities represent the most pressing security concerns in the Arctic. Until this occurs, the international community will not be able to adequately respond to a potential oil spill or grounded vessel in the region. While some analysts have expressed concern over the militarization of the Arctic, Baker and other panelists downplayed the possibility of military conflict in the Far North as a significant concern. She suggested that science-based diplomacy would be the best means to peacefully resolve disputes in the region.

Danila Bochkarev of the EastWest Institute in Brussels said that the development of sea routes (particularly the Northern Sea Route), border protection, and infrastructure development are among Russia’s top Arctic priorities. Bochkarev noted that the Arctic region has increased in economic importance to Russia and currently represents 11 percent of its GDP and 80 percent of the country’s discovered industrial gas. Aside from economic opportunities, melting Arctic ice has also allowed increased access to Russian territory, which is also viewed as a security concern by Russian officials. Other looming Russian concerns, noted Bochkarev, include the increasing internationalization of Arctic governance, competing claims for the Arctic continental shelf, and challenges to Russia’s sovereignty claim over the Northern Sea Route. He maintained that Russia has committed to following the principles of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea to peacefully resolve any territorial disputes.

Joël Plouffe of the Université du Québec à Montreal noted that Canada’s recently published “Statement on Canada’s Arctic Foreign Policy” highlights the Harper government’s desire to bolster economic development, protect the environment, strengthen its sovereignty claim, and improve governance in the Far North. Plouffe said that the Arctic policy document also shows Canada’s commitment to foster bilateral relationships among Arctic nations, particularly the United States. He noted that Canada has always promoted international cooperation in the Arctic and was one of the founding members of the Arctic Council. Canada’s Arctic policy, said Plouffe, also serves to fill a security gap in the Far North, an area of particular concern to the United States.

While Canada has demonstrated a willingness to engage coastal Arctic states on key environmental, security, and economic issues in the Far North, the Canadian government’s willingness to work with non-Arctic states is less clear, said Plouffe. Canada, he remarked, has yet to decide whether it would like to create an exclusive neighborhood of Arctic states to resolve governance issues, or if it is willing to include non-Arctic nations in international meetings and Arctic forums.

The Perspective of Non-Arctic Nations

“[W]e cannot be indifferent to a region whose melting ice sheet, volumes of water, and temperatures have a direct impact on Germany and Europe,” said Franz Thönnes, SPD Member of the German Bundestag. He explained that Germany and the European Union’s interest in the Arctic stem in part from the importance the EU places on the principles of stability and sustainability. EU interests in the Arctic also extend to the economic realm. Of particular interest, said Thönnes, are untapped Arctic oil and gas reserves and potential new shipping routes. He noted that the shipping route from Hamburg to Shanghai would be cut from 25,200 km to 17,000 km should the Northwest Passage become accessible. Given that Germany operates the world’s largest container fleet, access to such routes would be of major importance to Germany and other European maritime countries.

Ted McDorman of the University of Victoria stated that from an international law perspective, the Arctic Ocean is legally no different than any other ocean. Like other oceans, noted McDorman, there are significant gaps in governance that will require international cooperation to address. These include setting standards for shipping vessels passing through Arctic water and waterways, collaboration on marine science, and how to manage the Arctic marine ecosystem sustainably. According to McDorman, while some aspects of Arctic oil and gas development, such as drilling, will fall under domestic jurisdictions, international standards will still need to be negotiated to address potential oil spills or other environmental repercussions that may affect other countries. McDorman questioned whether an international treaty modeled after the Antarctic treaty would make sense for the Arctic region and he echoed comments by others that the idea is not supported by key Arctic players and is unlikely to move forward.

The Scandanavian countries vary in their level of Arctic engagement, said Timo Koivurova of Finland’s University of Lapland. Finland is currently developing a new Arctic strategy, and Iceland remains adamantly opposed to an exclusive Arctic Five governance structure while supporting active EU involvement in Arctic affairs. On the other hand, Sweden remains relatively inactive on the Arctic policy front. Koivurova noted that there are a growing number of non-Arctic nations – including China, South Korea, and Japan – that are seeking to become a part of the Arctic Council.

Koivurova closed by asking whether the Arctic Council could be reformed in a manner that allowed Arctic nations to retain their status while allowing greater representation for non-Arctic nations. Such reform, said Koivurova, may be necessary given the increasing desire and number of countries vying for a voice on Arctic governance.

Ken Crist is program associate with the Canada Institute at the Woodrow Wilson Center.

Photo Credit: “Arctic Sunrise,” courtesy of flickr user drurydrama (Len Radin). -

Yale Environment 360: ‘When The Water Ends: Africa’s Climate Conflicts’

›November 10, 2010 // By Wilson Center StaffOriginally posted on Yale Environment 360:

For thousands of years, nomadic herdsmen have roamed the harsh, semi-arid lowlands that stretch across 80 percent of Kenya and 60 percent of Ethiopia. Descendants of the oldest tribal societies in the world, they survive thanks to the animals they raise and the crops they grow, their travels determined by the search for water and grazing lands.These herdsmen have long been accustomed to adapting to a changing environment. But in recent years, they have faced challenges unlike any in living memory: As temperatures in the region have risen and water supplies have dwindled, the pastoralists have had to range more widely in search of suitable water and land. That search has brought tribal groups in Ethiopia and Kenya in increasing conflict, as pastoral communities kill each other over water and grass.

When the Water Ends, a 16-minute video produced by Yale Environment 360 in collaboration with MediaStorm, tells the story of this conflict and of the increasingly dire drought conditions facing parts of East Africa. To report this video, Evan Abramson, a 32-year-old photographer and videographer, spent two months in the region early this year, living among the herding communities. He returned with a tale that many climate scientists say will be increasingly common in the 21st century and beyond — how worsening drought in parts of Africa, the Middle East, and elsewhere will pit group against group, nation against nation. As one UN official told Abramson, the clashes between Kenyan and Ethiopian pastoralists represent “some of the world’s first climate-change conflicts.”

But the story recounted in When the Water Ends is not only about climate change. It’s also about how deforestation and land degradation — due in large part to population pressures — are exacting a toll on impoverished farmers and nomads as the earth grows ever more barren.

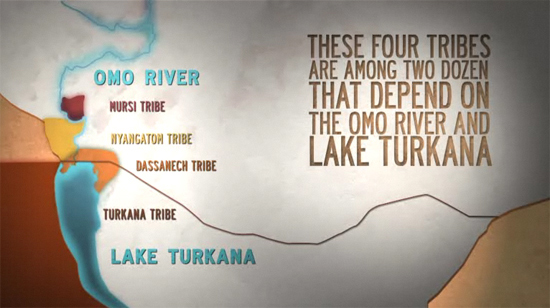

The video focuses on four groups of pastoralists — the Turkana of Kenya and the Dassanech, Nyangatom, and Mursi of Ethiopia — who are among the more than two dozen tribes whose lives and culture depend on the waters of the Omo River and the body of water into which it flows, Lake Turkana. For the past 40 years at least, Lake Turkana has steadily shrunk because of increased evaporation from higher temperatures and a steady reduction in the flow of the Omo due to less rainfall, increased diversion of water for irrigation, and upstream dam projects. As the lake has diminished, it has disappeared altogether from Ethiopian territory and retreated south into Kenya. The Dassanech people have followed the water, and in doing so have come into direct conflict with the Turkana of Kenya.

The result has been cross-border raids in which members of both groups kill each other, raid livestock, and torch huts. Many people in both tribes have been left without their traditional livelihoods and survive thanks to food aid from nonprofit organizations and the UN.

The future for the tribes of the Omo-Turkana basin looks bleak. Temperatures in the region have risen by about 2 degrees F since 1960. Droughts are occurring with a frequency and intensity not seen in recent memory. Areas once prone to drought every ten or eleven years are now experiencing a drought every two or three. Scientists say temperatures could well rise an additional 2 to 5 degrees F by 2060, which will almost certainly lead to even drier conditions in large parts of East Africa.

In addition, the Ethiopian government is building a dam on the upper Omo River — the largest hydropower project in sub-Saharan Africa — that will hold back water and prevent the river’s annual flood cycles, upon which more than 500,000 tribesmen in Ethiopia and 300,000 in Kenya depend for cultivation, grazing, and fishing.

The herdsmen who speak in this video are caught up in forces over which they have no real control. Although they have done almost nothing to generate the greenhouse gas emissions that cause global warming, they may already be among its first casualties. “I am really beaten by hunger,” says one elderly, rail-thin Nyangatom tribesman. “There is famine — people are dying here. This happened since the Turkana and the Kenyans started fighting with us. We fight over grazing lands. There is no peace at all.”

Watch When the Water Ends: Africa’s Climate Conflicts on Yale Environment 360.

For more on integrated PHE development and the Horn of Africa, see “The Beat on the Ground: Video: Population, Health, and Environment in Ethiopia” and “As Somalia Sinks, Neighbors Face a Fight to Stay Afloat,” on The New Security Beat. -

John Bongaarts on the Impacts of Demographic Change in the Developing World

› “The UN projects about 9.1 billion people by 2050, and then population growth will likely level off around 9.5 billion later in the century. Can the planet handle 9 billion? The answer is probably yes. Is it a desirable trajectory? The answer is no,” said John Bongaarts, vice president of the Policy Research Division at the Population Council, in this interview with ECSP.

“The UN projects about 9.1 billion people by 2050, and then population growth will likely level off around 9.5 billion later in the century. Can the planet handle 9 billion? The answer is probably yes. Is it a desirable trajectory? The answer is no,” said John Bongaarts, vice president of the Policy Research Division at the Population Council, in this interview with ECSP.

Although family planning was largely brushed aside by international policymakers following the 1994 UN International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo, Bongaarts said he is hopeful because it is now enjoying a higher profile globally – and receiving greater funding.

“I am optimistic about the understanding now, both in developing and developed world, and in the donor community, that [family planning] is an important issue that should be getting more attention,” Bongaarts said. “And therefore I think the chances of ending up with a positive demographic outlook are now larger than they were a few years ago.”

The “Pop Audio” series is also available as podcasts on iTunes. -

Demography and Women’s Empowerment: Urgency for Action?

›Why do Middle Eastern women participate in economic life at a rate lower than that of female citizens of other regions? According to Nadereh Chamlou, a senior advisor at the World Bank, restrictive social norms are to blame. At the Middle East and Environmental Change and Security Programs’ “Demography and Women’s Empowerment: Urgency for Action?” event, Chamlou argued that the region’s women must be empowered to participate in a more significant way if their countries are to effectively exploit, instead of squander, the current economic “window of opportunity.”According to Chamlou, the region is facing a “demographic window of opportunity” where its relatively high numbers of working-age people create the potential for rapid economic growth. However, Middle Eastern countries also have the highest dependency rates in the world. Without opening more economic opportunities for women, the region’s demographic window of opportunity will not be exploited to its full advantage.

Chamlou disputed the commonly held assumptions regarding the historic lack of female participation in the Middle East’s economic sphere, such as the belief that women abstain from joining the workforce because they do not possess the necessary education and skills. She cited statistics showing that the region’s women are represented at a near-equal level as men in secondary school, and to an even greater degree at the university level. They are also studying in marketable fields, disproving the theory that they are not acquiring employable skills.

A survey conducted by the World Bank in three Middle Eastern capital cities — Amman, Jordan; Cairo, Egypt; and Sana’a, Yemen — showed that negative male attitudes regarding women working outside the home were the most significant reason for poor female representation in the workforce. Notably, negative male attitudes restricted women’s participation far more than child-rearing duties. Despite the successful efforts of most Middle Eastern states to improve female education, conservative social norms that pose a barrier to female empowerment remain in place.

Chamlou concluded her remarks with three policy recommendations: 1) Focus on medium-educated, middle-class women; 2) Undertake more efforts to bring married women into the workforce; and 3) Place a greater emphasis on changing attitudes, particularly among conservative younger men, towards women working outside the home. Such changes could more effectively utilize the Middle East’s demographic window of opportunity.

Luke Hagberg is an intern and Haleh Esfandiari is director of the Middle East Program at the Wilson Center.

Sources: Population Reference Bureau.

Photo Credit: Adapted from “Obey Stikman,” courtesy of flickr user sabeth718. -

Rare Earths Intrigue: In Response to Chinese Ban, Japan and Vietnam Make a Deal

›November 2, 2010 // By Schuyler NullThe BBC is reporting that Japan has reached an agreement with Vietnam that will help provide a secure supply of rare earth minerals, after China reportedly stopped exports to Japan during an ongoing territorial dispute last month.

China produces nearly all (97 percent, according to the GAO) of the rare earth minerals used around the world, minerals that are used in many advanced electronics including mobile phones, missiles, and key components of cleaner energy tech. Japanese companies are expected to gain exclusive exploration and mining rights in northwest Vietnam in exchange for technical assistance on nuclear reactors.

China’s reported export freeze on rare earths raised warning flags in the region as well as in Washington, where fears over exclusive supply of the crucial minerals have been growing for some time – particularly in the defense community. (Although Bloomberg reports a new Pentagon study says it’s not such a big deal after all.) Control over and access to resources has become an important concern in East Asian diplomacy, as population and consumption in the region rises. For more, check out The New Security Beat’s coverage of the many diplomatic fault lines at play between the lower Mekong countries, China, and the United States, rare earth minerals and green energy, and the conflict potential of future resource scarcity.

Sources: BBC, Bloomberg, Government Accountability Office, The New York Times, TechNewsDaily.

Image Credit: Adapted from “The Huc Bridge, Hanoi,” courtesy of flickr user -aw-. -

Energy and Climate Change in the Context of National Security

›“Climate Change and Security,” a short briefing by Paul Rogers of the Oxford Research Group, examines the recent trend of framing climate change in terms of a national security threat and presents some of the pros and cons of this viewpoint. Rogers says the recent uptick in interest by the military is expected – and welcomed – because military planners often perform more long-term analyses than other policymakers. However, Rogers also cautions that the military, in its role as protector of the state, will naturally focus on adapting to the effects of climate change rather than preventing them. Thus, while this willingness to think long-term is appreciated, work remains to convince the international security community of the importance of carbon-cutting measures as well.

“Fueling the Future Force: Preparing the Department of Defense for a Post-Petroleum Era,” by Christine Parthemore and John Nagl of CNAS, is a comprehensive policy paper arguing for the U.S. military to aim for the ability to operate all its systems on non-petroleum fuels by 2040. Parthemore and Nagl outline a broad set of recommendations that address DOD’s consumption habits, leadership structure, finances, acquisition process, and mission goals. Notable, in the context of Paul Rogers’ warning, is that the authors’ argument is essentially one of supply and demand, rather than for cutting emissions to reduce the effects of climate change: “…while many of today’s weapons and transportation systems are unlikely to change dramatically or be replaced for decades, the petroleum needed to operate DOD assets may not remain affordable, or even reliably available, for the lifespans of these systems.” -

What You’re Saying: Uncommon Discourse on Climate-Security Linkages

›October 8, 2010 // By Wilson Center StaffMarc Levy’s response to Halvard Buhaug’s much ballyhooed paper, “Climate not to blame for African civil wars,” has drawn a number of thoughtful, interesting responses from our readers.

Idean Salehyan, of PRIO and the University of North Texas, defends Halvard’s paper and points out that Marshall Burke and his colleagues (see “Warming increases the risk of civil war in Africa”) are guilty of similar immodesty:I think Halvard would agree with all of this (I was a discussant on a previous version of this paper). His analysis simply points out problems with the Burke et al paper’s model specification. Buhaug’s is a modest contribution about model specification and appropriate data; it should be read as a response to an earlier paper rather than as a definitive statement about climate change and conflict. The headline is certainly provocative and unfortunate. However, he makes a useful corrective to overly simplistic causal claims, which typically dominate the popular literature on climate change and conflict. Yes, he could have been a little more modest with the title and with the conclusions, but then again, so could Burke and his colleagues.

Cullen Hendrix, of the Climate Change and African Political Stability team and also of the University of North Texas, highlights the complexity of the many degrees of conflict:Marc’s assessment is spot-on, so I won’t belabor the point other than to reiterate that Halvard is making a limited point about specific empirical relationships and causal pathways.

And Halvard himself chimes in as well:

In addition to the issues raised by Idean, I would add that there’s an unfortunate tendency to think about social conflict only through the lens of civil war. The environment and conflict literature is dominated by such studies. While civil war is undoubtedly an important subject of inquiry, there are many types of social conflict that could be related to climate change, warming, and environmental shocks. We need to pay increasing attention to conflict that doesn’t fit neatly into either the interstate or intrastate war paradigm.I believe we’re all pretty much on the same page here. My article has little to do with climate change per se; instead is focuses on short-term climate variability and the extent to which it affects the risk of intrastate armed conflict. Yet, as climate change is expected to bring about more variability and less predictability in future weather patterns, knowing how past climatic shocks or anomalies relate to armed conflict is relevant.

To follow the full conversation or respond yourself, see Marc Levy’s post, “On the Beat: Climate-Security Linkages Lost in Translation.”

I absolutely agree that breaking out of the state-centered understanding of conflict is an important next step. Similarly, as Marc points to, more research is needed on possible scope conditions and longer-term indirect causal links that might connect climate with violent behavior. That said, we should not ignore established, robust correlates of conflict. Climate change is not likely to bring about conflict and war in well-functioning societies, so improving the quality of governance and creating opportunities for sustainable economic growth, regardless of the specific role of climate in all of this, are likely to remain key policy priorities.

Photo Credit: “Symposium scene,” courtesy of flickr user Ian W Scott.