Showing posts from category economics.

-

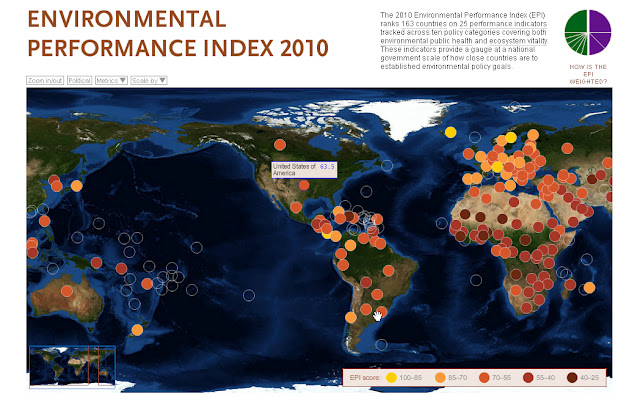

Measuring Ecosystem Vitality and Public Health With the Environmental Performance Index

›The Environmental Performance Index (EPI) is a comparative analytic tool for policymakers created jointly by Yale and Columbia Universities in collaboration with the World Economic Forum and Joint Research Centre of the European Commission. The EPI was created in 2006 and is updated biannually. Data is drawn from 25 performance indicators that fall under 10 well-established policy categories, including the environmental burden of disease, the effects of water on human health, and agriculture. The indicators serve as a “gauge at a national government scale of how close countries are to established environmental [and health] policy goals,” write the authors.

The EPI draws data from a diverse array of sources, such as the World Health Organization, Food and Agriculture Organization, University of New Hampshire, and World Resources Institute. Users can view visualizations of the compiled data via an interactive map and the data is also available in the form of rankings charts, individual country profiles, and country group comparisons. The interactive map also allows users to isolate performance indicators or policy categories in order to compare an individual country’s performance with global trends. Furthermore, indicators may be scaled to visually reflect a country’s performance in relation to drivers of environmental performance, like gross domestic product, level of corruption, and government effectiveness.

This tool is particularly useful because users can effectively leverage points for policy change by identifying linkages between environmental policy and other issue areas, such as public health or sanitation. The EPI enables policymakers to visually conceptualize problematic regions, optimize investments in environmental protection, and identify best practices.

The index’s greatest weakness is its inability to track changes in performance over time. A pilot project was launched last year that tracks whether a country has progressed or deteriorated in an area of environmental performance, but the authors note that the project has “raised more questions than answers,” particularly concerning data availability and interpretation. Additionally, there are gaps in the data. Although these gaps signify a data quality weakness, they also support the continued calls for increased data collection by governments and other organizations to better inform environmental decision-making. -

Yemen Beyond the Headlines: Losing the Battle to Balance Water Supply and Population Growth

›Part three of the “Yemen Beyond the Headlines: Population, Health, Natural Resources, and Institutions” event, held at the Wilson Center on May 18.

Overlooked in most news coverage of Yemen’s crisis is the country’s struggle to manage its limited natural resources – particularly its rapidly depleting groundwater – in the face of soaring population growth. At the recent Wilson Center event, “Yemen: Beyond the Headlines,” Yemen’s ambassador to Germany, Mohammed Al-Eryani, and Daniel Egel of the RAND Corporation outlined Yemen’s shaky prospects for economic development without more sustainable agricultural practices and more efficient water management. [Video Below]

With a population of more than 24 million and a total fertility rate (TFR) of 5.5 – nearly double the average TFR for the region – Yemen’s population is projected to grow to 36.7 million by 2025 and jump further to 61.6 million by mid-century, according to the latest UN projections. While those figures may not seem large by global standards, given Yemen’s already limited stocks of arable land and groundwater, the country’s rapid rate of growth may quickly outpace its resources.

“Already in a Crisis”: The Groundwater Deficit

Yemen’s per capita water supply is falling fast in the face of booming population growth and agricultural consumption, said Al-Eryani, a water engineer who founded Yemen’s Ministry of Water and the Environment. While the commonly accepted threshold for water scarcity is 1700 cubic meters or less per capita, Yemen’s per capita renewable water availability is now in the neighborhood of 120 cubic meters, he said.

Meanwhile, water scarcity has been exacerbated by erratic precipitation that has hit rainfall-dependent farmers especially hard. In a country with no real rivers or perennial streams, rainfall harvesting has long enabled agricultural production, as evidenced by the country’s many intricately terraced hillsides – “the food baskets of Yemen,” said Al-Eryani.

Yemenis have coped with shifting precipitation patterns by drawing more groundwater for irrigation and other domestic uses. While drilling wells has provided some short-term relief, the practice is unsustainable in the long term, creating a “water deficit,” Al-Eryani said, that continues to grow each year.

In the populous Sanaa basin, home to the Yemeni capital, consumption outweighs the aquifer’s natural rate of recharge by a factor of five to one and groundwater levels have been plummeting at six meters per year, he said. With only minimal government regulation of drilling, the country’s groundwater situation is poised to worsen, one of the reasons Al-Eryani declared his country is “already in a crisis.”

Stalled Economic Development

Yemen’s stalled economic development is particularly pronounced outside of urban areas, “where the resources are,” said Daniel Egel, citing the country’s failure to build modern transportation infrastructure and develop other economic activities besides farming. He called for the international development community to focus on creating jobs in rural areas, particularly by increasing the financing available for non-agricultural businesses and by improving secondary roads. In addition, he warned development actors to be aware of how gender inequality and local social structures, such as tribes, affect development efforts.

Given the country’s dependence on agriculture, water scarcity poses a threat to Yemen’s food security and its economic development. Three out of every four Yemeni villages depend on rainfall for irrigation, Egel said, making them highly vulnerable to unexpected climate change-induced shifts in precipitation patterns. Water scarcity also weakens the financial stability of Yemeni households, with the cost of water “accounting for about 10 percent of income during the dry season,” he said.

Averting a “Domino Effect”

Al-Eryani asserted that water management policies will “have to be designed in piecemeal fashion,” as no one single action will avert a catastrophe. He suggested a number of steps to alleviate the country’s growing water crunch, including:- Focus on the rural population, which makes up 70 percent of the population, has the highest fertility rates, and are the most reliant on agriculture;

- Move development efforts outside of Sanaa to other regions of the country;

- Increase investment in desalination technology for coastal areas;

- Increase water conservation in the agricultural sector; and,

- Exploit fossil groundwater aquifers in Yemen’s sparsely populated eastern reaches.

“The battle to strike a sustainable balance between population growth and sustainable water supplies was lost many years ago,” Al-Eryani said. “But maybe we can still win the war if we can undertake some of these measures.”

See parts one and two of “Yemen Beyond the Headlines: Population, Health, Natural Resources, and Institutions” for more from this Wilson Center event.

Sources: UN Population Division, World Bank.

Photo Credit: “At the fountain,” courtesy of flickr user Alexbip. -

Annie Murphy, International Reporting Project

Mozambique Coal Mine Brings Jobs, Concerns

›May 31, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Annie Murphy appeared on the International Reporting Project and NPR (follow the links for the accompanying audio track as well). Murphy appeared with three other IRP fellows at the Wilson Center on April 28 to talk about their experiences reporting abroad.

As developing countries grow, their need for raw materials grows, too.

This is the case for Brazil, a country that has much in common with the nation of Mozambique: Both have a mix of African and Portuguese influences; both are rich in natural resources; and both fought long and hard to throw off European colonialism.

Today, however, a Brazilian coal mine in Mozambique has some wondering what the energy demands of growing economies like Brazil really mean for African countries like Mozambique.

This coal mine in northwestern Mozambique is owned by the Brazilian company Vale — it’s a gaping, dark gray pit in the middle of a green, windswept savannah. Still under construction, it currently employees about 7,500 people.

Jose Manuel Guilengue, 23, a machine operator, says that he and a friend traveled 1,000 miles from the capital to get there, where they were both hired. That was a year ago. He now makes around $400 a month — which is more than four times the average salary in Mozambique.

According to the general manager overseeing construction, Osvaldo Adachi, this mine will produce about 11 million tons of coal each year, for at least three decades.

Continue reading and listen to the audio at the International Reporting Project.

Annie Murphy reported this story during a fellowship with the International Reporting Project (IRP). To hear more about Murphy and the IRP program, see the event summary for “Reporting on Global Health: A Conversation With the International Reporting Project Fellows.”

Photo Credit: Adapted from Mozambique, courtesy of flickr user F H Mira. -

Meeting Half the World’s Fuel Demands Without Affecting Farmland Joan Melcher, ChinaDialogue

Biofuels: The Grassroots Solution

›May 24, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Joan Melcher, appeared on ChinaDialogue.

The cultivation of biofuels – fuels derived from animal or plant matter – on marginal lands could meet up to half of the world’s current fuel consumption needs without affecting food crops or pastureland, environmental engineering researchers from America’s University of Illinois have concluded following a three-year study. The findings, according to lead author Ximing Cai, have significant implications not only for the production of biofuels but also the environmental quality of degraded lands.The study, the final report of which was published in the Journal of Environmental Science and Technology late last year, comes at a time of increasing global interest in biomass. The International Energy Agency predicts that biomass energy’s share of global energy supply will treble by 2050, to 30 percent. In March, the UK-based International Institute for Environment and Development called on national governments to take a “more sophisticated” approach to the energy source, putting it at the heart of energy strategies and ramping up investment in new technologies and research programs.

The University of Illinois project used cutting-edge land-use data collection methods to try to determine the potential for second-generation biofuels and perennial grasses, which do not compete with food crops and can be grown with less fertilizer and pesticide than conventional biofuels. They are considered to be an alternative to corn ethanol – a “first generation” biofuel – which has been criticized for the high amount of energy required to grow and harvest it, its intensive irrigation needs and the fact that corn used for biofuel now accounts for about 40 percent of the United States entire corn crop.

A critical concept of the study was that it only considered marginal land, defined as abandoned or degraded or of low quality for agricultural uses, Cai, who is civil and environmental engineering professor at the University of Illinois in the mid-western United States, told ChinaDialogue.

The team considered cultivation of three crops: switchgrass, miscanthus, and a class of perennial grasses referred to as low-impact high-diversity (LIHD).

Continue reading on ChinaDialogue.

Sources: Sources: International Energy Agency, Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, Reuters, University of Illinois.

Photo Credit: Adapted from “Biofuels,” courtesy jurvetson. -

Climate Change, Development, and the Law of Mother Earth

Bolivia: A Return to Pachamama?

›May 20, 2011 // By Christina DaggettIn Bolivia, environment-related contradictions abound: shrinking glaciers threaten the water supply of the booming capital city, La Paz, while unusually heavy rainfall triggers deadly landslides. The government is seeking to develop a strategic reserve of metals that could make Bolivia the “Saudi Arabia of lithium,” while politicians promote legal rights for “Mother Earth” and an end to capitalism.

This year has been particularly turbulent. In La Paz, landslides destroyed at least 400 homes and left 5,000 homeless. While the rain has been overwhelming at times, it has also been unreliable – an effect of the alternating climate phenomena La Niña and El Niño, experts say, which have grown more frequent in recent years and cause great variability in weather patterns. Bolivia has endured nine major droughts and 25 floods in the past three decades, a challenge for any country but particularly so for one of the poorest, least developed, and fastest growing (with a total fertility rate over three) in Latin America.

Environmental Justice or Radicalism?

Environmentalism has become a major force in national politics in part as a response to the climatic challenges faced by Bolivia. A new law seeks to grant the environment the same legal rights as citizens, including the right to clean air and water and the right to be free of pollution. (Voters in Ecuador approved a similar measure in 2008.) The law is seen as a return of respect to Pachamama, a much revered spiritual entity (akin to Mother Earth) for Bolivia’s indigenous population, who account for around 62 percent of the total population.

Though groundbreaking in its scope, the new law may prove difficult to enforce, given its lack of precedent and the lucrative business interests at stake (oil, gas, and mineral extraction accounted for 70 percent of Bolivia’s exports in 2010).

On the global stage, President Morales has issued perhaps the most aggressive calls yet for industrial countries to do more about climate change and compensate those countries that are already experiencing the effects. Bolivia refused to sign both the Copenhagen and Cancun climate agreements on grounds that the agreements were too weak. In Cancun, Morales gave a blistering speech:We have two paths: Either capitalism dies or Mother Earth dies. Either capitalism lives or Mother Earth lives. Of course, brothers and sisters, we are here for life, for humanity and for the rights of Mother Earth. Long live the rights of Mother Earth! Death to capitalism!

Bolivia’s stance has alienated potential allies: In 2010, the United States denied Bolivia climate aid funds worth $3 million because of its failure to sign the Copenhagen Accord.

Going… Going… Gone

Bolivia’s Chacaltaya glacier – estimated to be 18,000 years old – is today only a small patch of ice, the victim of rising temperatures from climate change, scientists say. Glaciologists suggest that temperatures have been steadily rising in Bolivia for the past 60 years and will continue to rise perhaps a further 3.5-4˚C over the next century – a change that would turn much of the country into desert.

Other Andean glaciers face a similar fate, according to the World Bank, which estimates that the loss of these glaciers threatens the water supply of some 30 million people and La Paz in particular, which, some experts say, could become one of the world’s first capitals to run out of water. The populations of La Paz and neighboring El Alto have been steadily growing – from less than 900,000 in 1950 to more than 2 million in 2011 – as more and more Bolivians are moving from the countryside to the city, putting pressure on an already dwindling water supply.

If the water scarcity situation continues to worsen, residents of the La Paz metropolitan area may migrate to other areas of the country, most likely eastward toward Bolivia’s largest and most prosperous city, Santa Cruz. Such migration, however, has the potential to inflame existing tensions between the western (indigenous) and eastern (mestizo) portions of the country.

Rising Prices, Rising Tension

The temperature is not the only thing on the rise in Bolivia; the price of food, too, is increasing. According to the World Food Program, since 2010, the price of pinto beans has risen 179 percent; flour, 44 percent; and rice, 33 percent. Shortages of sugar and other basic foodstuffs have been reported as well, leading to protests.

In early February, the BBC reported President Evo Morales was forced to abandon his plans to give a public speech after a group of protestors started throwing dynamite. A week later, nation-wide demonstrations paralyzed several cities, according to AFP, closing schools and disrupting services.

The Saudi Arabia of Lithium?

One way out for Bolivia’s economic woes might be its still nascent mineral extraction sector. Bolivia possesses an estimated 50 percent of the world’s lithium deposits (nine million tons, according to the U.S. Geological Survey), most of which is locked beneath the world’s largest salt flat, Salar de Uyuni. The size of these reserves has prompted some to dub Bolivia a potential “Saudi Arabia of lithium” – a title, it should be noted, that has also been bestowed upon Chile and Afghanistan.

Demand for lithium, which is used most notably in cell phones and electric car batteries, is expected to dramatically increase in the next 10 years as countries seek to lower their dependence on fossil fuels. Yet, some analysts have wondered if Bolivia’s lithium is needed, given the quality and current level of production of lithium from neighboring Chile and Argentina.

Others have questioned whether Bolivia has the necessary infrastructure to industrialize the extraction process or the ability to get its product to market, though Bolivia recently signed an agreement with neighboring Peru for port access. In an extensive report for The New Yorker, Lawrence Wright writes that “before Bolivia can hope to exploit a twenty-first century fuel, it must first develop the rudiments of a twentieth-century economy.” To this end, the Bolivian government last year announced a partnership with Iran to develop its lithium reserves – a surprising move, given Morales’ historical disdain for foreign investment.

Nexus of Climate, Security, Culture, and Development

The Uyuni salt flats are both a potent economic opportunity and one of the country’s most unspoiled natural wonders. How will Bolivia – a country of natural bounty and unique indigenous tradition – balance the need for development with its stated commitment to environmental principles?

Large-scale extraction may be worth the environmental cost, a La Paz economist told The Daily Mail: “We are one of the poorest countries on Earth with appalling life-expectancy rates. This is no time to be hard-headed. Without development our people will suffer. Getting bogged down in principles and politics doesn’t put food in people’s mouths.”

“The process that we are faced with internally is a difficult one. It’s no cup of tea. There are sectors and players at odds in this more environmentalist vision,” said Carlos Fuentes, a Bolivian government official, to The Latin American News Dispatch.

Sources: American University, BBC News, Bloomberg, Change.org, Christian Science Monitor, The Daily Mail, Democracy Now, Green Change, The Guardian, Instituto Nacional de Estadística de Bolivia, IPS News, Latin America News Dispatch, MercoPress, The New York Times, The New Yorker, Population Reference Bureau, PreventionWeb, Reliefweb, Reuters, SAGE, Tierramerica, USAID, U.S. Geological Survey, UNICEF, Upsidedownworld, Wired UK, The World Bank, Yahoo, Yes! Magazine.

Photo credit: “la paz,” courtesy of flickr user timsnell and “Isla Incahuasi – Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia,” courtesy of flickr user kk+. -

India’s Quest for a Lower Carbon Footprint

›

Between 1994 and 2007, India reduced its carbon dioxide emissions by 35 percent. As a result, the country’s emissions per capita now register at just over a ton per year – less than China (nearly five tons) and much less than the United States (18 tons). On May 10, Wilson Center Public Policy Scholar Ajay Shankardiscussed how India made these reductions, and what the nation plans to do to bring them down further in the decades ahead.

According to Shankar, several factors account for the 35 percent reductions. One is market-based, with high costs having discouraged heavy carbon-based energy consumption. India levied a “huge de facto” carbon tax on all commercial and industrial uses of electricity, which led to prices as much as 80 percent higher than the cost of supply. Another reason is legislation: New Delhi passed a robust energy conservation law. The private sector was a major contributor to the reductions; Shankar pointed out that India is now the world’s largest hub for small fuel-efficiency vehicles, as embodied by the Tata Motors corporation’s Nano car.

Shankar acknowledged the need for further carbon reductions. As India’s economic growth continues and its citizens become wealthier, carbon emissions will likely increase as more people buy cars and invest in air conditioning. Accordingly, the country has announced its intention, by 2020, to lower emissions by 20 to 25 percent from 2005 levels. He identified two carbon-reducing “opportunities” for India in the coming decades. One is to make irrigation more energy-efficient through the use of solar energy.

Another opportunity lies in India’s cities, where 300 to 400 million people are expected to flock over the next two to three decades. Urbanization presents a considerable carbon challenge, given the proliferation of carbon-emitting vehicles and AC units envisioned by such migration. Shankar spoke of the need for “smart cities” replete with “green buildings,” parks, and electric vehicles. He argued that India has created these types of cities before – including Chandigarh, the capital of Punjab Province, back in the 1950s.

Shankar stated that solar and nuclear energy constitute the “game-changers” for lessening the country’s carbon emissions. New Delhi hopes to generate 20,000 megawatts of solar capacity by 2020, with projections of grid parity by 2017 – meaning that in just several years, solar power could be as cheap to generate as fossil-fuel-driven electricity. He also underscored the priority New Delhi places on nuclear energy, noting that Prime Minister Manmohan Singh was willing to stake his political survival on the passing of a controversial civil nuclear deal with Washington because of nuclear’s environmental benefits. Shankar insisted that the Indian government will not be deterred by Japan’s recent nuclear crisis.

While Shankar described New Delhi’s 20 to 25 percent reductions goal as “ambitious,” he contended that he is more optimistic than he would have been several years ago about India’s prospects for attaining that objective. India, he concluded, must “rule out no option, and pursue every option intelligently.”

Michael Kugelman is program associate with the Asia Program at the Woodrow Wilson Center.

Photo Credit: “Tata nano,” courtesy of flickr user mjaniec. -

Watch: Edward Carr on Delivering Development and Rethinking Assumptions

›May 13, 2011 // By Schuyler NullWhile visiting West Africa first as an archaeologist, Edward Carr, an associate professor in the Department of Geography at the University of South Carolina and author of Delivering Development: Globalization’s Shoreline and the Road to a Sustainable Future, found that the villages in which he was working were far more resilient to the impacts of climate change than he expected. Increased frequency of drought, declines in rainfall, severe storms – these challenges are the sort of thing that can “totally destroy someone’s livelihood in a year,” he said in an interview with ECSP, “yet they were surviving and surviving really, really well.”

That experience and others challenged his understanding of “how I thought the world was supposed to work, how I’d been taught the world was supposed to work, versus what I was actually seeing happen on the ground,” said Carr. “I became so struck by what people were dealing with in the current context that my interest started to shift much more towards what they were doing now.”

Now serving as a AAAS fellow and the climate change coordinator for the Bureau for Democracy, Conflict, and Humanitarian Assistance at the U.S. Agency for International Development, Carr said he is trying to change how the U.S. government does development.

“The last 13 years of my career have been trying to figure out what’s actually happening on the ground first,” Carr said, and that led to writing Delivering Development.

“One of the key arguments I have is that the world does not work the way we assume it does – we are fundamentally misunderstanding what’s happening for most people living out, especially in rural areas, in the developing world,” said Carr. “The challenges they face are significant but not necessarily the ones we’re aimed at.”

For example, said Carr, “we see rising food prices globally and…the presumption is that the poorest people in the world are going to get really hammered by this.” But, he said, “That’s not entirely true, because a lot of the poorest people in the world living in rural areas have an option to just disconnect from markets completely – they go total subsistence if they need to.”

There’s an assumption that people shouldn’t be disconnecting like that, but, Carr pointed out, when new places are integrated into larger markets, “we’re also integrating them into new sources of risk that they may not be very well equipped to manage, and that becomes a really significant challenge.”

“We’re starting with the fundamental assumption that markets can be a solution, without necessarily really looking carefully at how markets can be part of the problem,” said Carr. -

How Does Organic Farming in the U.S. Affect Global Food Security?

›The feature story for last month’s Wilson Center newsletter, Centerpoint, was on the popular full-day conference “Rebuilding the U.S. Economy – One Heirloom Tomato at a Time,” hosted by the Program on America and the Global Economy in March. The conference focused on organic, local farming and the idea of creating “sustainable” food production that was healthier but also better for the economy than relying on imports from afar.

ECSP was asked to provide some international context for the discussion with a brief “Point of View.” I tried to paint a little bit of the big picture 21st century supply and demand story and give a sense of how today, globalization has helped linked everyone in this food security discussion:Dramatic events over the last year have shone a spotlight on the problem of global food security: massive fires in Russia, which reduced wheat supplies; famine and drought in Niger and Chad; and food price riots in the Middle East and elsewhere. These stresses come amid price spikes that echo the food crises of 2008 and reveal the linked nature of food security today and some of the fundamental challenges facing poor countries’ efforts to feed their growing populations.

What do you think: What’s the best way to inject the urgency that people looking at demographics and consumption rates around the world are feeling about global food security into a discussion about organic agriculture in the United States? Is there a tension between quality and quantity of food in the organic vs. agrobusiness debate that needs to be addressed in a global context? And what’s the role of policy in determining that balance?

In most countries, food insecurity is a symptom of poverty, poor governance, and/or poor infrastructure. For example, developed countries can often rebound from natural disasters relatively quickly. However, in drought-prone countries like Niger and Chad or flood victims like Pakistan and North Korea, such structural weaknesses leave them unable to bounce back as quickly from extreme events. This makes development efforts more difficult and can cause vulnerable countries to quickly become a burden on their neighbors or more prone to internal instability.

In the long term, reducing vulnerability in developing countries will be one of the most critical factors to ensuring global food security. But to meet the projected demand from increased consumption and continuing population growth, global yields must also increase.

The Green Revolution of the 1960-70s saved millions of lives by introducing heartier strains of rice and improving other staple crops in South and Southeast Asia, and most agree that a “Second Green Revolution” (whether or not it looks like the first) will likely be necessary. If so, the current tensions in the West over organic or sustainable practices versus agribusiness models will need to be reconciled in a way that can provide the most immediate help for the world’s hungry.

An important requirement, however, is that in a more resource-constrained world, these yields must be increased without destroying our future capacity. How we go about this, whether through traditional industry, organic techniques, or a mixture of both, will be one of the defining challenges of the 21st century.