-

Keith Schneider, Circle of Blue

Double Choke Point: Demand for Energy Tests Water Supply and Economic Stability in China and the U.S.

›The original version of this article, by Keith Schneider, appeared on Circle of Blue.

The coal mines of Inner Mongolia, China, and the oil and gas fields of the northern Great Plains in the United States are separated by 11,200 kilometers (7,000 miles) of ocean and 5,600 kilometers (3,500 miles) of land.

But, in form and function, the two fossil fuel development zones – the newest and largest in both nations – are illustrations of the escalating clash between energy demand and freshwater supplies that confront the stability of the world’s two biggest economies. How each nation responds will profoundly influence energy prices, food production, and economic security not only in their domestic markets, but also across the globe.

Both energy zones require enormous quantities of water – to mine, process, and use coal; to drill, fracture, and release oil and natural gas from deep layers of shale. Both zones also occur in some of the driest regions in China and the United States. And both zones reflect national priorities on fossil fuel production that are causing prodigious damage to the environment and putting enormous upward pressure on energy prices and inflation in China and the United States, say economists and scholars.

“To what degree is China taking into account the rising cost of energy as a factor in rising overall prices in their economy?” David Fridley said in an interview with Circle of Blue. Fridley is a staff scientist in the China Energy Group at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California. “What level of aggregate energy cost increases can China sustain before they tip over?”

“That’s where China’s next decade is heading – accommodating rising energy costs,” he added. “We’re already there in the United States. In 13 months, we’ll be fully in recession in this country; 9 percent of our GDP is energy costs. That’s higher than it’s been. When energy costs reach eight to nine percent of GDP, as they have in 2011, the economy is pushed into recession within a year.”

Continue reading on Circle of Blue.

Photo Credit: Used with permission, courtesy of J. Carl Ganter/Circle of Blue. In Ningxia Province, one of China’s largest coal producers, supplies of water to farmers have been cut 30 percent since 2008. -

Consumption and Global Growth: How Much Does Population Contribute to Carbon Emissions?

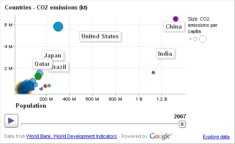

›July 6, 2011 // By Schuyler Null When discussing long-term population trends on this blog, we’ve mainly focused on demography’s interaction with social and economic development, the environment, conflict, and general state stability. In the context of climate change, population also plays a major role, but as Brian O’Neill of the National Center for Atmospheric Research put it at last year’s Society of Environmental Journalists conference, population is neither a silver bullet nor a red herring in the climate problem. Though it plays a major role, population is not the largest driver of global greenhouse gases emissions – consumption is.

When discussing long-term population trends on this blog, we’ve mainly focused on demography’s interaction with social and economic development, the environment, conflict, and general state stability. In the context of climate change, population also plays a major role, but as Brian O’Neill of the National Center for Atmospheric Research put it at last year’s Society of Environmental Journalists conference, population is neither a silver bullet nor a red herring in the climate problem. Though it plays a major role, population is not the largest driver of global greenhouse gases emissions – consumption is.

In Prosperity Without Growth, first published by the UK government’s Sustainable Development Commission and later by EarthScan as a book, economist Tim Jackson writes that it is “delusional” to rely on capitalism to transition to a “sustainable economy.” Because a capitalist economy is so reliant on consumption and constant growth, he concludes that it is not possible for it to limit greenhouse gas emissions to only 450 parts per million by 2050.

It’s worth noting that the UN has updated its population projections since Jackson’s original article. The medium variant projection for average annual population growth between now and 2050 is now about 0.75 percent (up from 0.70). The high variant projection bumps that growth rate up to 1.08 percent and the low down to 0.40 percent.

Either way, though population may play a major role in the development of certain regions, it plays a much smaller role in global CO2 emissions. In a fairly exhaustive post, Andrew Pendleton from Political Climate breaks down the math of Jackson’s most interesting conclusions and questions, including the role of population. He writes that the larger question is what will happen with consumption levels and technological advances:The argument goes like this. Growth (or decline) in emissions depend by definition on the product of three things: population growth (numbers of people), growth in income per person ($/person), and on the carbon intensity of economic activity (kgCO2/$). This last measure depends crucially on technology, and shows how far growth has been “decoupled” from carbon emissions. If population growth and economic growth are both positive, then carbon intensity must shrink at a faster rate than the other two if we are to slash emissions sufficiently.

Pendleton also brings up the prickly question of global inequity and how that impacts Jackson’s long-term assumptions:

Jackson calculates that to reach the 450 ppm stabilization target, carbon emissions would have to fall from today’s levels at an average rate of 4.9 percent a year every year to 2050. So overall, carbon intensity has to fall enough to get emissions down by that amount and offset population and income growth. Between now and 2050, population is expected to grow at an average of 0.7 percent and Jackson first considers an extrapolation of the rate of global economic growth since 1990 – 1.4 percent a year – into the future. Thus, to reach the target, carbon intensity will have to fall at an average rate of 4.9 + 0.7 + 1.4 = 7.0 percent a year every year between now and 2050. This is about 10 times the historic rate since 1990.

Pause at this stage, and take note that if there were no further economic growth, carbon intensity would still have to fall at a rate of 4.9 + 0.7 = 5.6 percent, or about eight times the rate over the last 20 years. To his credit, Jackson acknowledges this – as he puts it, decoupling is vital, with or without growth. Decoupling will require both huge innovation and investment in energy efficiency and low-carbon energy technologies. One question, to which we’ll return later, is whether and how you can get this if there is no economic growth.But Jackson doesn’t stop there. He goes on to point out that taking historical economic growth as a basis for the future means you accept a very unequal world. If we are serious about fairness, and poor countries catching up with rich countries, then the challenge is much, much bigger. In a scenario where all countries enjoy an income comparable with the European Union average by 2050 (taking into account 2.0 percent annual growth in that average between now and 2050 as well), then the numbers for the required rate of decoupling look like this: 4.9 percent a year cut in carbon emissions + 0.7 percent a year to offset population growth + 5.6 percent a year to offset economic growth = 11.2 percent per year, or about 15 times the historical rate.

To further complicate how population figures into all this, Brian O’Neill’s Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences article, “Global Demographic Trends and Future Carbon Emissions,” shows that urbanization and aging trends will have differential – and potentially offsetting – impacts on carbon emissions. Aging, particularly in industrialized countries, will reduce carbon emissions by up to 20 percent in the long term. On the other hand, urbanization, particularly in developing countries, could increase emissions by 25 percent.

What do you think? Is infinite growth possible? If so, how do you reconcile that with its effects on “spaceship Earth?” Do you rely on technology to improve efficiency? Do you call it a loss and hope the benefits of growth are worth it?

Sources: Political Climate, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Prosperity Without Growth (Jackson). -

Robert Jenkins, OpenDemocracy.net

Women, Food Security, and Peacebuilding: From Gender Essentialism To Market Fundamentalism

›July 5, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThat women’s engagement in resolving and recovering from conflict is crucial to sustainable peace has been an article of faith, and an element of international law, since the UN Security Council passed Resolution 1325 in 2000. It took a decade of missed opportunities, however, for the UN to develop a systematic action plan for redeeming the promise of 1325. The September 2010 Report of the Secretary-General on women’s participation in peacebuilding contains a concrete set of commitments for UN actors working in post-conflict settings.

-

Irene Kitzantides

In FOCUS Coffee and Community: Combining Agribusiness and Health in Rwanda

›June 29, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffDownload FOCUS Issue 22: “Coffee and Community: Combining Agribusiness and Health in Rwanda,” from the Wilson Center.

Rwanda, “the land of a thousand hills,” is also the land of 10 million people, making it the most densely populated country in Africa. Rwandans depend on ever-smaller plots of land for their food and livelihoods, leading to poverty, soil infertility, and food insecurity. Could Rwanda’s burgeoning specialty coffee industry hold the key to the country’s rebirth, reconciliation, and sustainable development?

In the latest issue of ESCP’s FOCUS series, author Irene Kitzantides describes the SPREAD Project’s integration of agribusiness development with community health care and education, including family planning. She outlines the project’s successes and challenges in its efforts to simultaneously improve both the lives and livelihoods of coffee farmers and their families. -

Tate Watkins, Short Sentences

Why Fund Both Farm Subsidies and Foreign Aid?

›June 27, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Tate Watkins, appeared on the blog Short Sentences.

The USDA routinely disburses $10 billion to $30 billion a year in farm subsidies. President Obama has allocated $47 billion for the State Department and USAID for the next fiscal year (not including proposed expenditures for Afghanistan, Iraq, and Pakistan).*

Why does the U.S. simultaneously fund domestic agricultural subsidies and foreign aid? The policies oppose each other. When it comes to promoting development opportunities for farmers around the globe, one of USAID’s ostensible goals, the left hand of the U.S. binds its right.

The origin of agricultural subsidies goes back at least to the first Agricultural Adjustment Act, enacted in 1933 as an attempt to help Depression farmers cope. Today farm interests justify subsidies in name of food security or, since 9/11, national security. But it’s widely acknowledged that the pastoral American family farmer, the image that farm interests present to the American people when the merits of subsidies are debated, do not benefit most from agricultural subsidies. Large corporate farmers do.

Continue reading on Short Sentences.

Photo Credit: Adapted from “YM009180,” courtesy of flickr user tpmartins, and “Badam Bagh Farm,” courtesy of flickr user U.S. Embassy Kabul Afghanistan. -

Women in Agriculture: Closing the Gender Gap for Development and World Hunger

›June 22, 2011 // By Kellie FurrProviding women with equal access to productive resources and opportunities may be the key to bolstering the struggling global agricultural sector and feeding communities living in extreme hunger, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) latest State of Food and Agriculture report, which this year is sub-titled, “Women in Agriculture: Closing the Gender Gap for Development.”

“Women are farmers, workers, and entrepreneurs, but almost everywhere they face more severe constraints than men in accessing productive resources, markets, and services,” write the authors. “This ‘gender gap’ hinders their productivity and reduces their contributions to the agriculture sector and to the achievement of broader economic and social development goals.”

Barriers to Productivity

Globally, women comprise 43 percent of the agricultural labor force, ranging from 20 percent in Latin America to 50 percent in southeastern and eastern Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, according to the report. But despite their significant global presence, female farmers face gender-specific constraints that hinder access to productive resources, financial support, information, and services required to be viable and competitive. “The yield gap between men and women averages around 20 to 30 percent, and most research finds that the gap is due to differences in resource use,” write the authors.

Generally, women are more likely than men to hold lower-wage, part-time, or seasonal positions and tend to get paid less even when they are more qualified. Furthermore, domestic and occupational lines are blurred for women, who are often not compensated for work that is closely related to domestic food preparation. Most significantly for agricultural productivity, women across the developing world often lack access to quality land, sometimes being barred from land ownership. This ban precludes female farmers from exercising managerial discretion over farming activities, such as entering contract farming agreements. Women also generally own less livestock and contract for less labor – two crucial assets for marketable agricultural production in many developing countries. Moreover, because of insufficient land and resources, women farmers are also more vulnerable to climate shocks.

Resource barriers for female farmers extend to education, finance, and technology as well. The authors observe that “female household heads in rural areas are disadvantaged with respect to human capital accumulation in most developing countries, regardless of region or level of economic development,” which represents a historical bias against females in education. Despite notable success observed in finance projects involving female farmers, gender bias exists in the financial system, which prevents women from bearing initial financial risk in order to increase long-term productivity gains. Sources of gender bias in the financial sector include legal barriers, cultural norms, lack of collateral, and institutional discrimination by public and private lenders. Due to the aforementioned lack of credit, labor, and education, women farmers are deficient in all aspects of technology, such as the acquisition of new equipment, information about new seed varietals and animal breeds, pest control measures, and management techniques.

Global Implications

Closing the gender gap could have profound implications for easing world hunger. According to the FAO, approximately 925 million people are currently undernourished, most of whom live in developing countries. If women were given all the inputs and support as men, agricultural output could increase by 2.5 to 4 percent in developing countries, potentially reducing the world’s hungry by 100 to 150 million people. “This report clearly confirms that the Millennium Development Goals on gender equality (MDG 3) and poverty and food security (MDG 1) are mutually reinforcing,” FAO Director-General Jacques Diouf argues in his introductory remarks.

Increasing the economic viability of women farmers may also translate into better infant and child health indicators – when women control additional income, they tend to allocate more of their earnings toward the health and well-being of their children. Closing the agricultural gap is “a proven strategy for enhancing the food security, nutrition, education, and health of children,” Diouf asserted. “Better fed, healthier children learn better and become more productive citizens. The benefits would span generations and pay large dividends in the future.”

Finally, the FAO notes that in addition to reducing child mortality rates, increasing female education and economic prosperity helps lower fertility rates, which over time increases human capital and can help drive a demographic transition towards lower dependency rates and higher per capita growth.

Closing the Gender Gap

“The conclusions are clear,” write the authors:1) Gender equality is good for agriculture, food security, and society; and

Though they note that “no simple ‘blueprint’ exists for achieving gender equality in agriculture,” the authors do recommend some basic principles to the development community, including working towards eliminating discrimination against women under the law, strengthening rural institutions and making them gender-aware, freeing women for more rewarding and productive activities, building the human capital of women and girls, bundling interventions, improving the collection and analysis of sex-disaggregated data, and making gender-aware agricultural policy decisions.

2) Governments, civil society, the private sector and individuals, working together, can support gender equality in agriculture and rural areas

Recognizing that “women will be a pivotal force behind achieving a food secure world,” the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) has actually launched initiatives aimed directly at closing the gender gap. The Feed the Future initiative, announced last spring, includes a heavy focus on gender equity and integration with small-scale farming initiatives. For example, the Office of Women in Development is supporting a three-year project in Liberia, “Integrated Agriculture for Women’s Empowerment,” that aims to train and support 1,500 small farmers in Lofa county, two-thirds of whom are women. And in Rwanda, USAID helped the Ministry of Agriculture and Animal Resources – headed by Dr. Agnes Kalibata – develop a national investment plan, which has been successful in bringing in donor support.

However, the FAO report does not offer specific feedback on programs like Feed the Future, which is arguably a crucial component of a truly comprehensive assessment on the current state of agriculture. Though they write that the State of Food Agriculture series is intended to simply be “science-based assessments of important issues,” the infancy of these food security efforts and the immediacy of the problems examined (see recent food price instability) creates an excellent opportunity for critical input. “Women in Agriculture” offers perhaps the most comprehensive report on the gender gap and development to date, but more specific critiques on the current efforts of USAID and others might make more of an impact in a field where the issues at play have been fairly clearly enumerated many times before.

Sources: Food and Agriculture Organization, The Hunger Project, International Fund for Agricultural Development, Population Action International, USAID.

Photo Credit: Adapted from “Ngurumo Village-Ntakira (Kenya),” courtesy of flickr user CGIAR Climate. -

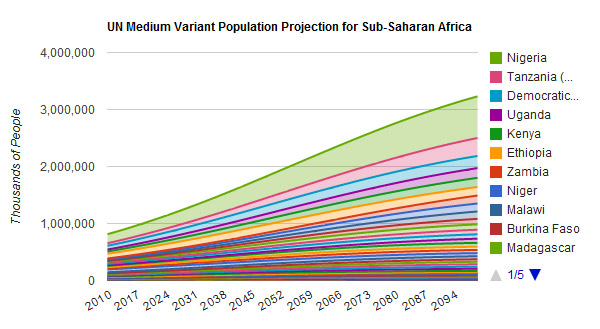

One in Three People Will Live in Sub-Saharan Africa in 2100, Says UN

›June 8, 2011 // By Schuyler NullBetween now and 2100, three out of every four people added to world population will live in sub-Saharan Africa. That’s what the medium variant of the UN’s world population projections estimates.* As we noted in our previous post on the latest UN numbers, Nigeria leads sub-Saharan growth, but other countries will also grow by major multiples: Tanzania and Somalia will be 7 times larger; Malawi more than 8 times; and Niger, to grow to more than 10 times its current population.

-

Watch: Younger Generation Will Prioritize Health, Education, Human Rights, Says Frederick Burkle

›June 7, 2011 // By Schuyler Null“Unfortunately, in the last two decades, when globalization became the mantra, it was primarily an economic mantra,” said Frederick Burkle, a senior fellow with the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative, visiting scientist at the Harvard School of Public Health, and senior public policy scholar at the Wilson Center. “The mantra was, ‘if you can improve the economy,” he said, “health, education, everything will follow.’”

“With the financial crisis, that proved not to be true,” Burkle said, and as a result, net expenditures in health and education have declined and the private sector, unfortunately, has not filled the gap.

“We really need to redefine globalization,” Burkle said. “And certainly economics will be there…but health, education, and human rights need to be just as dominant as the economics.”

Burke said he expects a gradual realignment of global priorities to come as younger generations come into decision-making roles. “They don’t have political clout right now,” he said, “but when they do…I think we’re going to see all these aspects that I mentioned – even the humanitarian profession becoming a career – accelerated.”

Showing posts from category economics.