Showing posts from category agriculture.

-

Preparing for the Impact of a Changing Climate on U.S. Humanitarian and Disaster Response

›Climate-related disasters could significantly impact military and civilian humanitarian response systems, so “an ounce of prevention now is worth a pound of cure in the future,” said CNA analyst E.D. McGrady at the Wilson Center launch of An Ounce of Preparation: Preparing for the Impact of a Changing Climate on U.S. Humanitarian and Disaster Response. The report, jointly published by CNA and Oxfam America, examines how climate change could affect the risk of natural disasters and U.S. government’s response to humanitarian emergencies. [Video Below]

Connecting the Dots Between Climate Change, Disaster Relief, and Security

The frequency of – and costs associated with – natural disasters are rising in part due to climate change, said McGrady, particularly for complex emergencies with underlying social, economic, or political problems, an overwhelming percentage of which occur in the developing world. In addition to the prospect of more intense storms and changing weather patterns, “economic and social stresses from agricultural disruption and [human] migration” will place an additional burden on already marginalized communities, he said.

Paul O’Brien, vice president for policy and campaigns at Oxfam America said the humanitarian assistance community needs to galvanize the American public and help them “connect the dots” between climate change, disaster relief, and security.

As a “threat multiplier,” climate change will likely exacerbate existing threats to natural and human systems, such as water scarcity, food insecurity, and global health deterioration, said Vice Admiral Lee Gunn, USN (ret.), president of CNA’s Institute for Public Research. Major General Richard Engel, USAF (ret.), of the National Intelligence Council identified shifting disease patterns and infrastructural damage as other potential security threats that could be exacerbated by climate change.

“We must fight disease, fight hunger, and help people overcome the environments which they face,” said Gunn. “Desperation and hopelessness are…the breeding ground for fanaticism.”

U.S. Response: Civilian and Military Efforts

The United States plays a very significant role in global humanitarian assistance, “typically providing 40 to 50 percent of resources in a given year,” said Marc Cohen, senior researcher on humanitarian policy and climate change at Oxfam America.

The civilian sector provides the majority of U.S. humanitarian assistance, said Cohen, including the USAID Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA) and the State Department’s Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration. These organizations provide leadership, funding, and food aid to developing countries in times of crisis, but also beforehand: “The internal rationale [of the Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance] is to reduce risk and increase the resilience of people to reduce the need for humanitarian assistance in the future,” said Edward Carr, climate change coordinator at USAID’s Bureau for Democracy, Conflict, and Humanitarian Assistance.

The U.S. military complements and strengthens civilian humanitarian assistance efforts by accessing areas that civilian teams cannot reach. The military can utilize its heavy lift capability, in-theater logistics, and command and control functions when transportation and communications infrastructures are impaired, said McGrady, and if the situation calls for it, they can also provide security. In addition, the military could share lessons learned from its considerable experience planning for complex, unanticipated contingencies with civilian agencies preparing for natural disasters.

“Forgotten Emergencies”

Already under enormous stress, humanitarian assistance and disaster response systems have persistent weaknesses, such as shortfalls in the amount and structure of funding, poor coordination, and lack of political gravitas, said Cohen.

Food-related aid is over-emphasized, said Cohen: “If we break down the shortfalls, we see that appeals for food aid get a better response than the type of response that would build assets and resilience…such as agricultural bolstering and public health measures.” Food aid often does not draw on local resources in developing countries, he said, which does little to improve long-term resilience.

“Assistance is not always based on need…but on short-term political considerations,” said Cohen, asserting that too much aid is supplied to areas such as Afghanistan and Iraq, while “forgotten emergencies,” such as the Niger food crisis, receive far too little. Furthermore, aid distribution needs to be carried out more carefully at the local scale as well: During complex emergencies in fragile states, any perception of unequal assistance has the potential to create “blowback” if the United States is identified with only one side of a conflict.

Engel added that many of the problems associated with humanitarian assistance will be further compounded by increasing urbanization, which concentrates people in areas that do not have adequate or resilient infrastructure for agriculture, water, or energy.

Preparing for Unknown Unknowns

A “whole of government approach” that utilizes the strengths of both the military and civilian humanitarian sectors is necessary to ensure that the United States is prepared for the future effects of climate change on complex emergencies in developing countries, said Engel.

In order to “cut long-term costs and avoid some of the worst outcomes,” the report recommends that the United States:

Cohen singled out “structural budget issues” that pit appropriations for protracted emergencies in places like Iraq, Afghanistan, and Darfur against unanticipated emergencies, like the 2010 earthquake in Haiti. Disaster-risk reduction investments are not a “budgetary trick” to repackage disaster appropriations but a practical way to make more efficient use of current resources, he said: “Studies show that the return on disaster-risk reduction is about seven to one – a pretty good cost-benefit ratio.”- Increase the efficiency of aid delivery by changing the budgetary process;

- Reduce the demand by increasing the resilience of marginal (or close-to-marginal) societies now;

- Be given the legal authority to purchase food aid from local producers in developing countries to bolster delivery efficiency, support economic development, and build agricultural resilience;

- Establish OFDA as the single lead federal agency for disaster preparedness and response, in practice as well as theory;

- Hold an OFDA-led biannual humanitarian planning exercise that is focused in addressing key drivers of climate-related emergencies; and,

- Develop a policy framework on military involvement in humanitarian response.

Edward Carr said that OFDA is already integrating disaster-risk reduction into its other strengths, such as early warning systems, conflict management and mitigation, democracy and governance, and food aid. However, to build truly effective resilience, these efforts must be tied to larger issues, such as economic development and general climate adaptation, he said.

“What worries me most are not actually the things I do know, but the things we cannot predict right now,” said Carr. “These are the biggest challenges we face.”

“Pakistan Floods: thousands of houses destroyed, roads are submerged,” courtesy of flickr user Oxfam International. -

Tate Watkins, Short Sentences

Why Fund Both Farm Subsidies and Foreign Aid?

›June 27, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Tate Watkins, appeared on the blog Short Sentences.

The USDA routinely disburses $10 billion to $30 billion a year in farm subsidies. President Obama has allocated $47 billion for the State Department and USAID for the next fiscal year (not including proposed expenditures for Afghanistan, Iraq, and Pakistan).*

Why does the U.S. simultaneously fund domestic agricultural subsidies and foreign aid? The policies oppose each other. When it comes to promoting development opportunities for farmers around the globe, one of USAID’s ostensible goals, the left hand of the U.S. binds its right.

The origin of agricultural subsidies goes back at least to the first Agricultural Adjustment Act, enacted in 1933 as an attempt to help Depression farmers cope. Today farm interests justify subsidies in name of food security or, since 9/11, national security. But it’s widely acknowledged that the pastoral American family farmer, the image that farm interests present to the American people when the merits of subsidies are debated, do not benefit most from agricultural subsidies. Large corporate farmers do.

Continue reading on Short Sentences.

Photo Credit: Adapted from “YM009180,” courtesy of flickr user tpmartins, and “Badam Bagh Farm,” courtesy of flickr user U.S. Embassy Kabul Afghanistan. -

Women in Agriculture: Closing the Gender Gap for Development and World Hunger

›June 22, 2011 // By Kellie FurrProviding women with equal access to productive resources and opportunities may be the key to bolstering the struggling global agricultural sector and feeding communities living in extreme hunger, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) latest State of Food and Agriculture report, which this year is sub-titled, “Women in Agriculture: Closing the Gender Gap for Development.”

“Women are farmers, workers, and entrepreneurs, but almost everywhere they face more severe constraints than men in accessing productive resources, markets, and services,” write the authors. “This ‘gender gap’ hinders their productivity and reduces their contributions to the agriculture sector and to the achievement of broader economic and social development goals.”

Barriers to Productivity

Globally, women comprise 43 percent of the agricultural labor force, ranging from 20 percent in Latin America to 50 percent in southeastern and eastern Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, according to the report. But despite their significant global presence, female farmers face gender-specific constraints that hinder access to productive resources, financial support, information, and services required to be viable and competitive. “The yield gap between men and women averages around 20 to 30 percent, and most research finds that the gap is due to differences in resource use,” write the authors.

Generally, women are more likely than men to hold lower-wage, part-time, or seasonal positions and tend to get paid less even when they are more qualified. Furthermore, domestic and occupational lines are blurred for women, who are often not compensated for work that is closely related to domestic food preparation. Most significantly for agricultural productivity, women across the developing world often lack access to quality land, sometimes being barred from land ownership. This ban precludes female farmers from exercising managerial discretion over farming activities, such as entering contract farming agreements. Women also generally own less livestock and contract for less labor – two crucial assets for marketable agricultural production in many developing countries. Moreover, because of insufficient land and resources, women farmers are also more vulnerable to climate shocks.

Resource barriers for female farmers extend to education, finance, and technology as well. The authors observe that “female household heads in rural areas are disadvantaged with respect to human capital accumulation in most developing countries, regardless of region or level of economic development,” which represents a historical bias against females in education. Despite notable success observed in finance projects involving female farmers, gender bias exists in the financial system, which prevents women from bearing initial financial risk in order to increase long-term productivity gains. Sources of gender bias in the financial sector include legal barriers, cultural norms, lack of collateral, and institutional discrimination by public and private lenders. Due to the aforementioned lack of credit, labor, and education, women farmers are deficient in all aspects of technology, such as the acquisition of new equipment, information about new seed varietals and animal breeds, pest control measures, and management techniques.

Global Implications

Closing the gender gap could have profound implications for easing world hunger. According to the FAO, approximately 925 million people are currently undernourished, most of whom live in developing countries. If women were given all the inputs and support as men, agricultural output could increase by 2.5 to 4 percent in developing countries, potentially reducing the world’s hungry by 100 to 150 million people. “This report clearly confirms that the Millennium Development Goals on gender equality (MDG 3) and poverty and food security (MDG 1) are mutually reinforcing,” FAO Director-General Jacques Diouf argues in his introductory remarks.

Increasing the economic viability of women farmers may also translate into better infant and child health indicators – when women control additional income, they tend to allocate more of their earnings toward the health and well-being of their children. Closing the agricultural gap is “a proven strategy for enhancing the food security, nutrition, education, and health of children,” Diouf asserted. “Better fed, healthier children learn better and become more productive citizens. The benefits would span generations and pay large dividends in the future.”

Finally, the FAO notes that in addition to reducing child mortality rates, increasing female education and economic prosperity helps lower fertility rates, which over time increases human capital and can help drive a demographic transition towards lower dependency rates and higher per capita growth.

Closing the Gender Gap

“The conclusions are clear,” write the authors:1) Gender equality is good for agriculture, food security, and society; and

Though they note that “no simple ‘blueprint’ exists for achieving gender equality in agriculture,” the authors do recommend some basic principles to the development community, including working towards eliminating discrimination against women under the law, strengthening rural institutions and making them gender-aware, freeing women for more rewarding and productive activities, building the human capital of women and girls, bundling interventions, improving the collection and analysis of sex-disaggregated data, and making gender-aware agricultural policy decisions.

2) Governments, civil society, the private sector and individuals, working together, can support gender equality in agriculture and rural areas

Recognizing that “women will be a pivotal force behind achieving a food secure world,” the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) has actually launched initiatives aimed directly at closing the gender gap. The Feed the Future initiative, announced last spring, includes a heavy focus on gender equity and integration with small-scale farming initiatives. For example, the Office of Women in Development is supporting a three-year project in Liberia, “Integrated Agriculture for Women’s Empowerment,” that aims to train and support 1,500 small farmers in Lofa county, two-thirds of whom are women. And in Rwanda, USAID helped the Ministry of Agriculture and Animal Resources – headed by Dr. Agnes Kalibata – develop a national investment plan, which has been successful in bringing in donor support.

However, the FAO report does not offer specific feedback on programs like Feed the Future, which is arguably a crucial component of a truly comprehensive assessment on the current state of agriculture. Though they write that the State of Food Agriculture series is intended to simply be “science-based assessments of important issues,” the infancy of these food security efforts and the immediacy of the problems examined (see recent food price instability) creates an excellent opportunity for critical input. “Women in Agriculture” offers perhaps the most comprehensive report on the gender gap and development to date, but more specific critiques on the current efforts of USAID and others might make more of an impact in a field where the issues at play have been fairly clearly enumerated many times before.

Sources: Food and Agriculture Organization, The Hunger Project, International Fund for Agricultural Development, Population Action International, USAID.

Photo Credit: Adapted from “Ngurumo Village-Ntakira (Kenya),” courtesy of flickr user CGIAR Climate. -

Tim Siegenbeek van Heukelom, State-of-Affairs

Food Security in Kenya’s Yala Swamp

›June 21, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Tim Siegenbeek van Heukelom, appeared on State-of-Affairs.

In West Kenya on the Northeastern shore of Lake Victoria, the Yala swamp wetland is one of Kenya’s biodiversity hotspots. The Yala swamp also supports several communities that utilize the wetland’s natural resources to support their families and secure their livelihoods. Even more, many people recognize the swamp’s extraordinary potential as agricultural land to significantly boost Kenya’s food security. These are three widely diverse interests, which may seem to be difficult to reconcile. Yet, with proper management, sufficient investment and effective communication, a differentiated utilization of the Yala swamp can be realized through a system of multiple land use. This will be a difficult but certainly not unrealistic objective.

A Brief History

The most recent development of the Yala swamp was undertaken by Dominion Farms, a subsidiary of a privately held company from the United States investing in agricultural development. The reclamation and development of the swamp, however, is far from a new phenomenon.

The intention of the Kenyan government to transform parts of the Yala swamp into agricultural land for food production goes back as far as the early 1970s. Around that time, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands was consulted extensively by the Kenyan government for technical assistance on reclamation of the swamp and the feasibility of agricultural production.

Throughout the 1980s numerous reports were commissioned by the Kenyan Ministry for Energy and Regional Development and the Lake Basin Development Authority to the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Reports like the “Yala Integrated Development Plan” and the “Yala Swamp Reclamation and Development Project” focused in depth on the potential of the development of the swamp and made recommendations on practical matters, such as drainage and irrigation, soil analysis, agriculture, marketing, environmental aspects, employment opportunities, human settlement, management, and financial planning.

As a result, small-scale reclamation and development of the swamp land was undertaken throughout the 1980s and 1990s under the supervision of the Lake Basin Development Authority. The development of the swamp was partially successful, yet its scale was small and financial benefits were too marginal. Major investment was therefore required to extend the scale of the project.

Then, in 2003, an American investor expressed interest to make significant long-term investments into bringing parts of the swamp into agricultural production. Subsequently, a lease for 45 years was negotiated between Dominion Farms and the Siaya and Bondo County Councils to bring into agricultural production some 7,000 hectares of the Yala swamp. The whole Yala swamp wetland covers 17,500 hectares, which means that Dominion Farms is allowed to reclaim and develop roughly 40 percent of the swamp.

Protracted Conflict

Since the early days of the arrival of the foreign investor in 2004, there has been lingering tension and occasional flares of conflict between the communities surrounding the project site, third parties (i.e. government officials, politicians, NGOs, CBOs, environmentalists), and the investor.

The most commonly touted complaint is that Dominion Farms “grabbed” the communities’ land. While it is hard to trace back the exact procedures and individuals that were involved, there are clear contracts with the Siaya and Bondo County Councils that substantiate the transfer of land-use to Dominion Farms for a period of 45 years. Some claim, however, that the negotiation process for the lease was entrenched in bribery and corruption, yet no one has been able to show this author a single trace of evidence to substantiate these accusations. Similarly, there are complaints by local residents that they were never consulted in the negotiation process – where they should have been, as they rightly point out that the swamp is community trust land. However, the land is held in trust by the relevant county council for the community. The county council should therefore initiate consultations with the local communities and residents to get their approval to lease the land to third parties. So it appears that some of the resentment over the loss of parts of the swamp should not be directed at the foreign investor but rather target the local county council and their procedures.

Continue reading on State-of-Affairs. -

Keith Schneider, Circle of Blue

China’s Other Looming Choke Point: Food Production

›The original version of this article, by Keith Schneider, appeared on Circle of Blue.

Even along the middle reaches of the Yellow River, which irrigates 402,000 hectares (993,000 acres) of farmland north of the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region’s provincial capital, there is still no mistaking the smell of dry earth and diesel fuel, the abiding scents of a desert province that is also among China’s most efficient grain producers.

Ningxia farmers have relied on the Yellow River since 221 BCE, when Qin Dynasty engineers clawed narrow trenches from the sand, introducing some of the first instances of irrigated agriculture on earth. Despite persistent droughts, in each of the last five years irrigation has made it possible for annual harvests to increase by an average of 100,000 metric tons.

The 2010 harvest of 3.5 million metric tons was nearly double what it was in 1990. The 3.9 million people who live and work on Ningxia’s 1.2 million farms, most no larger than three-quarters of a hectare (1.6 acres), produce the highest yields of rice and corn in the nine-province Yellow River Basin, according to central government crop statistics.

In sum, the farm productivity of this small northern China region – about the same size as West Virginia and located 1,200 kilometers (745 miles) to the west of the Bohai Sea – reflects the major shifts in geography and cultivation practices over the last generation that have made China both self-sufficient in food production and the largest grain grower in the world.

Yet Chinese farm officials here and academic authorities in Beijing are becoming increasingly concerned that China does not have enough water, good land, and energy to sustain its agricultural prowess. As Circle of Blue and the Woodrow Wilson Center’s China Environment Forum have reported in the Choke Point: China series, momentous competing trends – rising energy demand, accelerating modernization, and diminishing freshwater resources – are putting the country’s energy production and security at risk.

The very same trends also threaten China’s farm productivity. Last year, the national farm sector and the coal sector combined used 85 percent of the 599 billion cubic meters (158 trillion gallons) of water used in China.

Continue reading on Circle of Blue.

Keith Schneider is the senior editor of Circle of Blue and was a New York Times national correspondent for over a decade, where he continues to report as a special writer on energy, real estate, business, and technology.

Photo Credit: Used with permission, courtesy of J. Carl Ganter/Circle of Blue. -

Michael Kugelman, Dawn

Aquaculture’s Promise for Food-Insecure Pakistan

›June 7, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Michael Kugelman, appeared on Dawn.

“Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day,” the ancient Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu famously said. “Teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime.”

For years, this adage has helped frame debates across a variety of disciplines. However, while globally influential, it is by no means universally applicable – as the sad realities of Sindh make painfully clear. In this parched, food-insecure region flush with fishermen and farmers, people have long known how to fish. The problem is that with water bodies shriveling up, there are increasingly fewer fish to catch. Many impoverished residents would be grateful for a single fish, given their struggles to secure a day’s worth of food.

Pakistan’s natural resource constraints know no provincial borders, yet they are notably severe in Sindh. Water tables are plummeting, with great volumes of Indus River flows diverted upstream to satiate agricultural and urban demand in Punjab.

Sindh’s water security is further threatened by population growth and global warming, and by the water-intensive, large-scale farming envisioned by foreign investors jockeying for agricultural land.

With surface water supplies threatened, users are increasingly tapping groundwater resources – yet according to the Pakistan Council of Research in Water Resources, a staggering 95 percent of the province’s shallow groundwater supplies are bacteriologically contaminated. This is unsurprising, given the technical deficiencies and inefficiency that characterize Sindh’s water treatment facilities.

In a province where so many livelihoods are tied to water availability and food production, water stress aggravates food insecurity and threatens economic well-being. A recent World Bank report concludes that Pakistan’s poorest spend at least 70 percent of their meager incomes on food – and undoubtedly many of them hail from Sindh. According to data from the Pakistan Agricultural Research Council, some of the province’s small farmers spend a whopping 87 percent of their incomes on food.

Continue reading on Dawn.

Michael Kugelman is a program associate for the Asia Program at the Woodrow Wilson Center.

Photo Credit: A child stands amongst buildings destroyed by the floods in Sindh province, courtesy of flickr user DFID – UK Department for International Development. -

Measuring Ecosystem Vitality and Public Health With the Environmental Performance Index

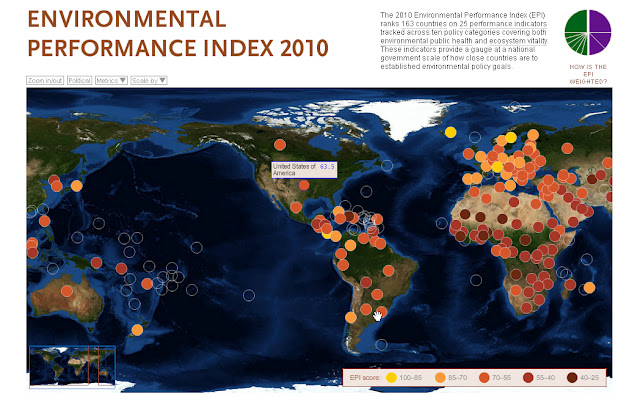

›The Environmental Performance Index (EPI) is a comparative analytic tool for policymakers created jointly by Yale and Columbia Universities in collaboration with the World Economic Forum and Joint Research Centre of the European Commission. The EPI was created in 2006 and is updated biannually. Data is drawn from 25 performance indicators that fall under 10 well-established policy categories, including the environmental burden of disease, the effects of water on human health, and agriculture. The indicators serve as a “gauge at a national government scale of how close countries are to established environmental [and health] policy goals,” write the authors.

The EPI draws data from a diverse array of sources, such as the World Health Organization, Food and Agriculture Organization, University of New Hampshire, and World Resources Institute. Users can view visualizations of the compiled data via an interactive map and the data is also available in the form of rankings charts, individual country profiles, and country group comparisons. The interactive map also allows users to isolate performance indicators or policy categories in order to compare an individual country’s performance with global trends. Furthermore, indicators may be scaled to visually reflect a country’s performance in relation to drivers of environmental performance, like gross domestic product, level of corruption, and government effectiveness.

This tool is particularly useful because users can effectively leverage points for policy change by identifying linkages between environmental policy and other issue areas, such as public health or sanitation. The EPI enables policymakers to visually conceptualize problematic regions, optimize investments in environmental protection, and identify best practices.

The index’s greatest weakness is its inability to track changes in performance over time. A pilot project was launched last year that tracks whether a country has progressed or deteriorated in an area of environmental performance, but the authors note that the project has “raised more questions than answers,” particularly concerning data availability and interpretation. Additionally, there are gaps in the data. Although these gaps signify a data quality weakness, they also support the continued calls for increased data collection by governments and other organizations to better inform environmental decision-making. -

Yemen Beyond the Headlines: Losing the Battle to Balance Water Supply and Population Growth

›Part three of the “Yemen Beyond the Headlines: Population, Health, Natural Resources, and Institutions” event, held at the Wilson Center on May 18.

Overlooked in most news coverage of Yemen’s crisis is the country’s struggle to manage its limited natural resources – particularly its rapidly depleting groundwater – in the face of soaring population growth. At the recent Wilson Center event, “Yemen: Beyond the Headlines,” Yemen’s ambassador to Germany, Mohammed Al-Eryani, and Daniel Egel of the RAND Corporation outlined Yemen’s shaky prospects for economic development without more sustainable agricultural practices and more efficient water management. [Video Below]

With a population of more than 24 million and a total fertility rate (TFR) of 5.5 – nearly double the average TFR for the region – Yemen’s population is projected to grow to 36.7 million by 2025 and jump further to 61.6 million by mid-century, according to the latest UN projections. While those figures may not seem large by global standards, given Yemen’s already limited stocks of arable land and groundwater, the country’s rapid rate of growth may quickly outpace its resources.

“Already in a Crisis”: The Groundwater Deficit

Yemen’s per capita water supply is falling fast in the face of booming population growth and agricultural consumption, said Al-Eryani, a water engineer who founded Yemen’s Ministry of Water and the Environment. While the commonly accepted threshold for water scarcity is 1700 cubic meters or less per capita, Yemen’s per capita renewable water availability is now in the neighborhood of 120 cubic meters, he said.

Meanwhile, water scarcity has been exacerbated by erratic precipitation that has hit rainfall-dependent farmers especially hard. In a country with no real rivers or perennial streams, rainfall harvesting has long enabled agricultural production, as evidenced by the country’s many intricately terraced hillsides – “the food baskets of Yemen,” said Al-Eryani.

Yemenis have coped with shifting precipitation patterns by drawing more groundwater for irrigation and other domestic uses. While drilling wells has provided some short-term relief, the practice is unsustainable in the long term, creating a “water deficit,” Al-Eryani said, that continues to grow each year.

In the populous Sanaa basin, home to the Yemeni capital, consumption outweighs the aquifer’s natural rate of recharge by a factor of five to one and groundwater levels have been plummeting at six meters per year, he said. With only minimal government regulation of drilling, the country’s groundwater situation is poised to worsen, one of the reasons Al-Eryani declared his country is “already in a crisis.”

Stalled Economic Development

Yemen’s stalled economic development is particularly pronounced outside of urban areas, “where the resources are,” said Daniel Egel, citing the country’s failure to build modern transportation infrastructure and develop other economic activities besides farming. He called for the international development community to focus on creating jobs in rural areas, particularly by increasing the financing available for non-agricultural businesses and by improving secondary roads. In addition, he warned development actors to be aware of how gender inequality and local social structures, such as tribes, affect development efforts.

Given the country’s dependence on agriculture, water scarcity poses a threat to Yemen’s food security and its economic development. Three out of every four Yemeni villages depend on rainfall for irrigation, Egel said, making them highly vulnerable to unexpected climate change-induced shifts in precipitation patterns. Water scarcity also weakens the financial stability of Yemeni households, with the cost of water “accounting for about 10 percent of income during the dry season,” he said.

Averting a “Domino Effect”

Al-Eryani asserted that water management policies will “have to be designed in piecemeal fashion,” as no one single action will avert a catastrophe. He suggested a number of steps to alleviate the country’s growing water crunch, including:- Focus on the rural population, which makes up 70 percent of the population, has the highest fertility rates, and are the most reliant on agriculture;

- Move development efforts outside of Sanaa to other regions of the country;

- Increase investment in desalination technology for coastal areas;

- Increase water conservation in the agricultural sector; and,

- Exploit fossil groundwater aquifers in Yemen’s sparsely populated eastern reaches.

“The battle to strike a sustainable balance between population growth and sustainable water supplies was lost many years ago,” Al-Eryani said. “But maybe we can still win the war if we can undertake some of these measures.”

See parts one and two of “Yemen Beyond the Headlines: Population, Health, Natural Resources, and Institutions” for more from this Wilson Center event.

Sources: UN Population Division, World Bank.

Photo Credit: “At the fountain,” courtesy of flickr user Alexbip.