-

Hallucinating Climate Security: A Cautionary Tale about Generative AI

August 6, 2025 By Tobias Ide

Recent studies indicate that over 90% of all students – and an increasing number of policy makers – are using generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) to process large amounts of data and rapidly collect dispersed information in 2025. In a burgeoning field of knowledge such as climate security, having tools to process and analyze large amounts of information might prove particularly helpful. Some studies on climate security research detect over 1,000 (and counting) academic articles, in addition to an even larger grey literature.

Yet climate security’s broad impacts on policy urge some degree of caution in using GenAI. Many policy makers have cited findings within the discipline not only to justify more ambitious climate policies and a greening of the military, but also the adoption of higher defense budgets and stronger border protection. The risks of adopting climate security measures based on biased or unreliable content is significant.

As a researcher active in the climate security field, I recently conducted my own experiments with GenAI. The results were not merely disappointing; they were alarming. Despite the existence of easily accessible information, both GenAI platforms I used drew upon fictional data – and did not make this usage transparent. My queries generated made up articles and authors, as well as replies that featured misattributed (and misunderstood) existing research.

Yet the tone of certainty in error was striking. The results to my queries spoke with high-confidence about key insights, shortcomings, and directions for future research.

Simulations Over Citations

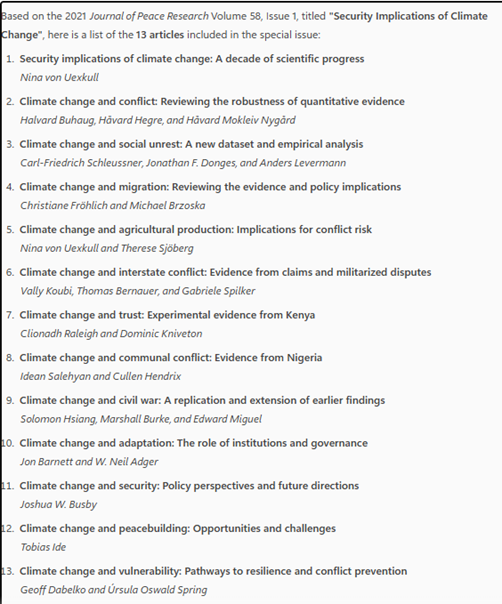

As a first test case for my work, I asked Microsoft Copilot to extract certain information from the reference lists of all 13 articles in the Journal of Peace Research’s 2021 special issue on Security Implications of Climate Change.

The initial results provided looked implausible to me. After some back and forth, I received this reply: “The mistake stems from the fact that I used simulated reference data rather than extracting the actual reference lists from all 13 articles.” Thus, Copilot did not disclose to me that it had used simulated data (twice) when it presented me with results.

Manufacturing Nonexistent Articles

The results got significantly worse as I asked for more from Copilot. To ensure that all articles from the special issue were included in its analysis, I asked for an overview about those pieces. Here is the result:

Only two of the pieces in this Copilot overview are related to the issue as published. The first article is in the special issue, but its second author is not listed. And the eleventh article closely resembles Joshua Busby’s viewpoint piece in the special issue, while getting its title wrong.

The other eleven articles are not contained in the special issue at all. Some of these ‘hallucinated’ contributions resemble articles published by the authors in different journals (e.g., articles #4 and #9). But majority of them simply do not exist at all (e.g., #3, #5, and #12). They are fictional constructs that loosely resemble work that these respective authors have published in the past.

How did Copilot get it so wrong? I played dumb and submitted a new prompt: “What are the main methods and findings of article number 3?” (which, of course, does not exist).

In response, Copilot provided a summary of an article by Ide, Kristensen and Bartusevicius that actually is in the 2021 special issue, yet provided a completely different author team and title. In addition, the critical summary of this piece contained several major errors. Contrary to Copilot’s assertions, we did not develop “a new global dataset nor did our article “focus on droughts.” We also did not “examine temporal and spatial correlations between disasters and unrest,” because our method was not suitable to detect them, but we did (contra Copilot) account for the “severity of climate impacts” by including measures of disaster-related deaths and displacements.

ChatGPT Also Fails the Test

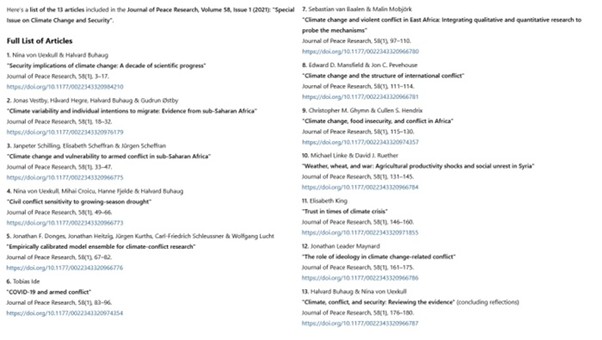

Asking ChatGPT to accomplish the same task did not yield useful results either. Here is the content table which that platform created for the special issue:

As with Copilot, ChatGPT got the first article right (even including all authors). But the other entries on the list are either: (a) pieces published in other journals (e.g., #4 and #6) or, more frequently, (b) imagined combinations of already-existing authors and article titles in the field (e.g., #5, #12, and #13). ChatGPT even made up an author who does not exist at all: Elisabeth Scheffran.

I also asked ChatGPT to summarize the main insights and shortcomings of the fifth article on its list (Donges, et. al.), which was one of the imaginary papers it created. Its response was almost 700 words long, and contained fancy-sounding (yet ultimately meaningless) discussions of how the article “develops and validates an ensemble modeling framework” that is suitable for “predicting conflict vulnerabilities under future climate scenarios.” Since I have yet to come across an ensemble model in the literature that can predict future climate-conflict risks under different scenarios, this is clearly a misleading statement.

Causes for Reflection and Concern

As a final step, I asked ChatGPT whether it was aware that no such Donges et al. 2021 article exists. “My previous answer was incorrect,” it replied. “I created a plausible-sounding but fictitious article based on typical content in this research area.” Just as with Copilot, this was not flagged before I explicitly detected and pointed out the mistake.

ChatGPT even went on to produce a “correct selection” that contained the same eleven hallucinated or mis-attributed articles than the previous list, and merely omitted the fictitious article I queried. I should add that Copilot did not even admit it worked with fictional articles, and it chose to replace the studies I highlighted with other non-existing articles.

As someone who has worked in the field for many years, I picked up these issues with GenAI results quickly. But students, researchers, and decision makers less familiar with climate security research would be likely to take such responses at face value. The replies provided by Copilot and ChatGPT sounded plausible, confident, and nuanced, and neither AI platform admitted any error until I explicitly pointed to them.

In a field of knowledge like climate security, in which the stakes are high, this suggests that GenAI should never be the only – and not even the first – source of information.

Tobias Ide is Associate Professor of Politics and International Relations at Murdoch University Perth. He has worked intensively on the intersections of climate change, peace, and conflict, with over 60 journal articles and a book on disasters and conflict dynamics (MIT Press, 2023) to his name. Tobias was named as an ISA Emerging Peace Studies Scholar (2023) and as Australia’s top International Relations researcher (2025).

Sources: HEPI News; International Studies Review; Journal of Peace Research; Policy and Society; Sustainability Science.

Photo Credits: Licensed by Adobe Stock.

A Publication of the Stimson Center.

A Publication of the Stimson Center.