Yearly archive for 2011.

Show all posts

-

Watch: Eric Kaufmann on How Demography Is Enhancing Religious Fundamentalism

›May 24, 2011 // By Schuyler Null“There’s a belief, often amongst political scientists and social scientists, that demography is somehow passive and that it doesn’t really matter,” said Eric Kaufmann, author of Shall the Religious Inherit the Earth: Demography and Politics in the 21st Century and professor at Birkbeck College, University of London in this interview with ECSP. “Part of the message of this book is that demography can lead to social and political change.”

“In this case what I’m looking at is the way that demography can change the religious landscape,” Kaufmann said. “It can actually enhance the power of religion, especially religious fundamentalism in societies throughout the world.”

“Purely secular people, who have no religious affiliation, they are leading the move towards very low levels of fertility, even down to the level of one child per woman,” Kaufmann said. On the other hand, fundamentalists are reacting to this trend and deliberately deciding not to make the demographic transition, he said. “In doing so, the gap between secular and religious widens” and is actually more pronounced in places where the two groups collide.

“You can see this in the Muslim world,” said Kaufmann. “If you look at urban areas such as the Nile Delta and Cairo, in those urban cities, women are who are most in favor of Shariah have twice the family size of women who are most opposed to Shariah, whereas in the Egyptian countryside, the difference is much less because they haven’t been exposed to the same modernizing pressures.”

These dynamics affect the Western world as well, especially when you factor in migration, said Kaufmann: “The fact that almost all the world’s population growth is occurring in the developing world, which is largely religious, means that a lot of people are moving from religious parts of the world to secular parts of the world,” he said. “That effects, for example, countries like the United States or in Western Europe, which are receiving immigrants, and it means in the case of Western Europe – which is a very secular environment – that immigrants bring not only ethnic change but on the back of that, religious change; they make their societies more religious.” -

Meeting Half the World’s Fuel Demands Without Affecting Farmland Joan Melcher, ChinaDialogue

Biofuels: The Grassroots Solution

›May 24, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Joan Melcher, appeared on ChinaDialogue.

The cultivation of biofuels – fuels derived from animal or plant matter – on marginal lands could meet up to half of the world’s current fuel consumption needs without affecting food crops or pastureland, environmental engineering researchers from America’s University of Illinois have concluded following a three-year study. The findings, according to lead author Ximing Cai, have significant implications not only for the production of biofuels but also the environmental quality of degraded lands.The study, the final report of which was published in the Journal of Environmental Science and Technology late last year, comes at a time of increasing global interest in biomass. The International Energy Agency predicts that biomass energy’s share of global energy supply will treble by 2050, to 30 percent. In March, the UK-based International Institute for Environment and Development called on national governments to take a “more sophisticated” approach to the energy source, putting it at the heart of energy strategies and ramping up investment in new technologies and research programs.

The University of Illinois project used cutting-edge land-use data collection methods to try to determine the potential for second-generation biofuels and perennial grasses, which do not compete with food crops and can be grown with less fertilizer and pesticide than conventional biofuels. They are considered to be an alternative to corn ethanol – a “first generation” biofuel – which has been criticized for the high amount of energy required to grow and harvest it, its intensive irrigation needs and the fact that corn used for biofuel now accounts for about 40 percent of the United States entire corn crop.

A critical concept of the study was that it only considered marginal land, defined as abandoned or degraded or of low quality for agricultural uses, Cai, who is civil and environmental engineering professor at the University of Illinois in the mid-western United States, told ChinaDialogue.

The team considered cultivation of three crops: switchgrass, miscanthus, and a class of perennial grasses referred to as low-impact high-diversity (LIHD).

Continue reading on ChinaDialogue.

Sources: Sources: International Energy Agency, Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, Reuters, University of Illinois.

Photo Credit: Adapted from “Biofuels,” courtesy jurvetson. -

Mapping Population and Climate Change

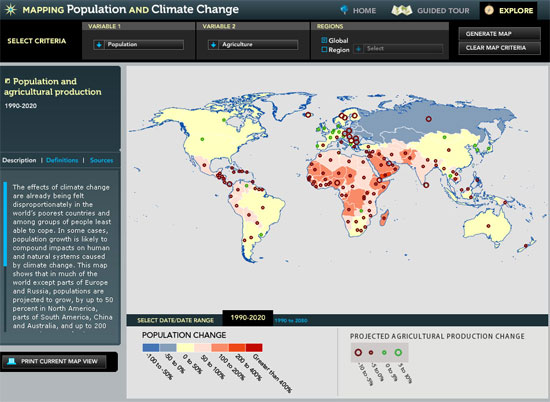

›Climate change, population growth, unmet family planning needs, water scarcity, and changes in agricultural production are among the global challenges confronting governments and ordinary citizens in the 21st century. With the interactive feature “Mapping Population and Climate Change” from Population Action International, users can generate maps using a variety of variables to see how these challenges relate over time.

Users can choose between variables such as water scarcity or stress, temperature change, soil moisture, population, agriculture, need for family planning, and resilience. Global or regional views are available, as well as different data ranges: contemporary, short-term projections (to the year 2035), and long-term projections (2090).

In the example featured above, the variables of population change and agricultural production change were chosen for the time period 1990-2020. Unfortunately, no country-specific data is given, though descriptions in the side-bar offer some helpful explanations of the selected trends.

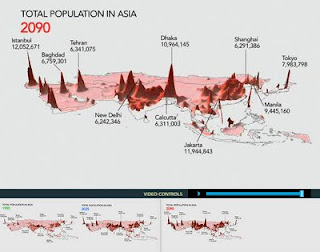

In addition, users can view three-dimensional maps of population growth in Africa and Asia for the years 1990, 2035, and 2090. These maps visually demonstrate the projected dramatic increases in population of these regions by the end of the century. According to the latest UN estimates, most of the world’s population growth will come from Africa and Asia due to persistently high fertility rates.

Image Credit: Population Action International. -

Rosemarie Calvert, Center for a Better Life

Winning Hearts and Minds: An Interview with Chief Naval Officer Admiral Gary Roughead

›May 23, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffThe original version of this article, by Rosemarie Calvert, appeared in the Center for a Better Life’s livebetter magazine.

Few people understand “smart” power as well as Chief Naval Officer (CNO) Admiral Gary Roughead. To this ingenious, adept leader of the world’s largest and most powerful navy, it’s not just about military strategy or political science; it’s about heart. It’s about the measure of a man with regard to honor, courage and commitment. And, it’s about appreciation and respect for the natural world. As one of the U.S. Defense Department’s most powerful decision-makers, Roughead has helped mold a new breed of sailor who understands that preventing war is just as important as winning war – that creating partners is more important than creating opponents. Add mission mandates such as humanitarian assistance, disaster relief, and environmental stewardship, and it’s clear why Roughead and his brand of smart power are having a profound impact on international peace, national security, and natural security.

Engendering Environmental Advocacy

“You don’t live on the ocean and not love it. My appreciation for the environment came from a very early age – from just loving to be on the water. It’s something that’s had a very strong impact on me,” explains Roughead, who grew up in North Africa where his father worked in the oil business. He and his family lived along an uninhabited area of coastline where his father’s company built a power plant and refinery to process and transport Libya’s huge oil field finds to offshore tankers.

“We were the first people to move there; I was still in grammar school. The beauty in being the first was that the coastline was absolutely pristine. Even before school, I would get up and go skin diving. There were beautiful reefs, and fish were everywhere. The vegetation was just incredible. The company built an offshore loading area a few miles off the beach with 36-inch pipes pumping crude oil out to where these big supertankers would come in. Back then, there wasn’t a high regard for the environment, so when storms would kick-up and ships got underway in a hurry, they would just cast them off and all that oil would go into the ocean.

“Fast forward about five years, and the last time I went skin diving I didn’t see a living thing. The vegetation was dead. At that time I was visiting my folks on summer leave from the Naval Academy. There were periods when I would skin dive and then surface after being down about 35-40 feet, and my lungs would be ready to burst. I’d look up, having moved from my original location, and see this massive oil slick. And, I’d go, ‘Oh gosh…no!’ But, you didn’t have any choice. I would come home and actually have to clean the oil off with kerosene because it was caked on me.

“I saw and experienced environmental devastation, and it had an effect on me. Being at sea all the time – I love going to sea and seeing everything about it – drove me to the views I have. I really do think there’s compatibility between the Navy and the environment. We have things we must accomplish, but we can do them cleanly and responsibly. That’s what we’ve tried to demonstrate to those who have different views – that there has to be compatibility between the two.”

Continue reading on the Center for a Better Life.

Rosemarie Calvert is the publisher and editorial director of livebetter magazine and director of the Center for a Better Life.

Photo Credit: Adapted from “USS Nitze underway with ships from U.S. Navy, Coast Guard and foreign navies,” courtesy of flickr user Official U.S. Navy Imagery. -

Climate Change, Development, and the Law of Mother Earth

Bolivia: A Return to Pachamama?

›May 20, 2011 // By Christina DaggettIn Bolivia, environment-related contradictions abound: shrinking glaciers threaten the water supply of the booming capital city, La Paz, while unusually heavy rainfall triggers deadly landslides. The government is seeking to develop a strategic reserve of metals that could make Bolivia the “Saudi Arabia of lithium,” while politicians promote legal rights for “Mother Earth” and an end to capitalism.

This year has been particularly turbulent. In La Paz, landslides destroyed at least 400 homes and left 5,000 homeless. While the rain has been overwhelming at times, it has also been unreliable – an effect of the alternating climate phenomena La Niña and El Niño, experts say, which have grown more frequent in recent years and cause great variability in weather patterns. Bolivia has endured nine major droughts and 25 floods in the past three decades, a challenge for any country but particularly so for one of the poorest, least developed, and fastest growing (with a total fertility rate over three) in Latin America.

Environmental Justice or Radicalism?

Environmentalism has become a major force in national politics in part as a response to the climatic challenges faced by Bolivia. A new law seeks to grant the environment the same legal rights as citizens, including the right to clean air and water and the right to be free of pollution. (Voters in Ecuador approved a similar measure in 2008.) The law is seen as a return of respect to Pachamama, a much revered spiritual entity (akin to Mother Earth) for Bolivia’s indigenous population, who account for around 62 percent of the total population.

Though groundbreaking in its scope, the new law may prove difficult to enforce, given its lack of precedent and the lucrative business interests at stake (oil, gas, and mineral extraction accounted for 70 percent of Bolivia’s exports in 2010).

On the global stage, President Morales has issued perhaps the most aggressive calls yet for industrial countries to do more about climate change and compensate those countries that are already experiencing the effects. Bolivia refused to sign both the Copenhagen and Cancun climate agreements on grounds that the agreements were too weak. In Cancun, Morales gave a blistering speech:We have two paths: Either capitalism dies or Mother Earth dies. Either capitalism lives or Mother Earth lives. Of course, brothers and sisters, we are here for life, for humanity and for the rights of Mother Earth. Long live the rights of Mother Earth! Death to capitalism!

Bolivia’s stance has alienated potential allies: In 2010, the United States denied Bolivia climate aid funds worth $3 million because of its failure to sign the Copenhagen Accord.

Going… Going… Gone

Bolivia’s Chacaltaya glacier – estimated to be 18,000 years old – is today only a small patch of ice, the victim of rising temperatures from climate change, scientists say. Glaciologists suggest that temperatures have been steadily rising in Bolivia for the past 60 years and will continue to rise perhaps a further 3.5-4˚C over the next century – a change that would turn much of the country into desert.

Other Andean glaciers face a similar fate, according to the World Bank, which estimates that the loss of these glaciers threatens the water supply of some 30 million people and La Paz in particular, which, some experts say, could become one of the world’s first capitals to run out of water. The populations of La Paz and neighboring El Alto have been steadily growing – from less than 900,000 in 1950 to more than 2 million in 2011 – as more and more Bolivians are moving from the countryside to the city, putting pressure on an already dwindling water supply.

If the water scarcity situation continues to worsen, residents of the La Paz metropolitan area may migrate to other areas of the country, most likely eastward toward Bolivia’s largest and most prosperous city, Santa Cruz. Such migration, however, has the potential to inflame existing tensions between the western (indigenous) and eastern (mestizo) portions of the country.

Rising Prices, Rising Tension

The temperature is not the only thing on the rise in Bolivia; the price of food, too, is increasing. According to the World Food Program, since 2010, the price of pinto beans has risen 179 percent; flour, 44 percent; and rice, 33 percent. Shortages of sugar and other basic foodstuffs have been reported as well, leading to protests.

In early February, the BBC reported President Evo Morales was forced to abandon his plans to give a public speech after a group of protestors started throwing dynamite. A week later, nation-wide demonstrations paralyzed several cities, according to AFP, closing schools and disrupting services.

The Saudi Arabia of Lithium?

One way out for Bolivia’s economic woes might be its still nascent mineral extraction sector. Bolivia possesses an estimated 50 percent of the world’s lithium deposits (nine million tons, according to the U.S. Geological Survey), most of which is locked beneath the world’s largest salt flat, Salar de Uyuni. The size of these reserves has prompted some to dub Bolivia a potential “Saudi Arabia of lithium” – a title, it should be noted, that has also been bestowed upon Chile and Afghanistan.

Demand for lithium, which is used most notably in cell phones and electric car batteries, is expected to dramatically increase in the next 10 years as countries seek to lower their dependence on fossil fuels. Yet, some analysts have wondered if Bolivia’s lithium is needed, given the quality and current level of production of lithium from neighboring Chile and Argentina.

Others have questioned whether Bolivia has the necessary infrastructure to industrialize the extraction process or the ability to get its product to market, though Bolivia recently signed an agreement with neighboring Peru for port access. In an extensive report for The New Yorker, Lawrence Wright writes that “before Bolivia can hope to exploit a twenty-first century fuel, it must first develop the rudiments of a twentieth-century economy.” To this end, the Bolivian government last year announced a partnership with Iran to develop its lithium reserves – a surprising move, given Morales’ historical disdain for foreign investment.

Nexus of Climate, Security, Culture, and Development

The Uyuni salt flats are both a potent economic opportunity and one of the country’s most unspoiled natural wonders. How will Bolivia – a country of natural bounty and unique indigenous tradition – balance the need for development with its stated commitment to environmental principles?

Large-scale extraction may be worth the environmental cost, a La Paz economist told The Daily Mail: “We are one of the poorest countries on Earth with appalling life-expectancy rates. This is no time to be hard-headed. Without development our people will suffer. Getting bogged down in principles and politics doesn’t put food in people’s mouths.”

“The process that we are faced with internally is a difficult one. It’s no cup of tea. There are sectors and players at odds in this more environmentalist vision,” said Carlos Fuentes, a Bolivian government official, to The Latin American News Dispatch.

Sources: American University, BBC News, Bloomberg, Change.org, Christian Science Monitor, The Daily Mail, Democracy Now, Green Change, The Guardian, Instituto Nacional de Estadística de Bolivia, IPS News, Latin America News Dispatch, MercoPress, The New York Times, The New Yorker, Population Reference Bureau, PreventionWeb, Reliefweb, Reuters, SAGE, Tierramerica, USAID, U.S. Geological Survey, UNICEF, Upsidedownworld, Wired UK, The World Bank, Yahoo, Yes! Magazine.

Photo credit: “la paz,” courtesy of flickr user timsnell and “Isla Incahuasi – Salar de Uyuni, Bolivia,” courtesy of flickr user kk+. -

“The Second Front in the War on Terror”

USAID, Muslim Separatists, and Politics in the Southern Philippines

›For some years after the terrorist attacks of 9/11, the existence of violent Muslim separatists on the southern Philippine island of Mindanao gave U.S. officials significant cause for concern. In 2005, for example, the U.S. embassy charge d’affaires to the Philippines, Joseph Mussomeli, told reporters that “certain portions of Mindanao are so lawless, so porous…that you run the risk of it becoming like an Afghanistan situation. Mindanao is almost, forgive the poor religious pun, the new Mecca for terrorism.” During the Bush administration, officials referred to the region as a “second front” in the War on Terror: the region was once seen as a “new Afghanistan” that “threatened to become an epicenter of Al Qaeda.” [Video Below]

Nevertheless, as noted by Wilson Center Fellow Patricio Abinales at an Asia Program event on May 11, U.S. efforts to co-opt and pacify separatist guerrillas have proven remarkably successful in some areas of the islands. Some commentators have highlighted the role of the U.S. military in bringing a relative sense of security to troubled regions, noting that Mindanao presents a “future model for counterinsurgency.” However, Abinales’s research shows the military activities have had little effect, often because troops are stationed far from potential areas of conflict. Instead, it is the civilian side of the American presence that has dampened conflict in the war zones of the southern Philippines.

Abinales specifically explored the factors behind the success of the U.S. Agency for International Development’s (USAID) Growth with Equity in Mindanao (GEM) program in demobilizing and reintegrating 28,000 separatist guerrillas of the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF), as well as the long-term political consequences of this accomplishment.

“Arms to Farms”

Usually, USAID programs are organized on the basis of grants for specific and limited projects. In contrast, GEM arose as a long-term umbrella organization that oversees the disbursement and management of American funding across a number of long-term projects. Coordinators are trained directly in Mindanao and are encouraged to “go native,” living in the area and becoming part of the community. GEM prioritizes cultural understanding, respect for community leaders, an appreciation of the important role that women play in local societies, and sensitivity to potential divisions within separatist groups and their security concerns vis-à-vis the Philippine government.

There has often been a general tendency for aid organizations to associate the demobilization of warring groups with disarmament. While Philippine officials on Mindanao have sometimes tried this approach, cash-for-guns amnesty schemes have opened up opportunities for corruption and have not been particularly effective. Understanding that one of the major concerns of guerrilla rebels is exploitation by corrupt government officials, GEM established an “Arms to Farms” scheme, whereby Muslim rebels are trained to engage in agriculture, but are not encouraged to put away their weapons. In this way, the program keeps potential guerrillas and Al Qaeda recruits busy with legitimate and peaceful economic activity, while it assuages their concerns about the threat from corrupt government officials, who may otherwise take the fruits of agricultural labor by force.

In fact, Abinales noted that one of the keys to GEM’s success is that the organization has never submitted to the official local authorities, and has largely been allowed a free reign by Manila to conduct its activities on Mindanao. It is precisely because the state has not been successful in delivering welfare regimes which provide stability to the area that GEM is seen as an alternate source of development and security in the region. Moreover, because of GEM’s activities, other American officials are allowed relatively free access, and are even welcomed into areas where the authority of the Philippine government holds no sway. Most of GEM’s activities are conducted with the MNLF, which has maintained its own official treaties and agreements with Manila since the 1970s. However, the American organization is beginning to enter the territory of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, a splinter group of the MNLF that rejects relations with the national government outright, but one whose leaders are jealous of the development gains the MNLF has made under GEM.

Abinales was quick to point out that although GEM’s activities have been successful, they are tailor-made to specific circumstances. It is therefore difficult to present them as a generalized model that can be applied to other separatist conflicts. Nevertheless, Abinales’s work suggests that government agencies working on counterinsurgency efforts elsewhere might do well to examine the benefits of the flexible civilian approaches to conflict resolution formed with a deep understanding of the concerns of the specific communities involved.

Bryce Wakefield is program associate with the Asia Program at the Woodrow Wilson Center. -

The Walk to Water in Conflict-Affected Areas

›May 18, 2011 // By Wilson Center StaffConstituting a majority of the world’s poor and at the same time bearing responsibility for half the world’s food production and most family health and nutrition needs, women and girls regularly bear the burden of procuring water for multiple household and agricultural uses. When water is not readily accessible, they become a highly vulnerable group. Where access to water is limited, the walk to water is too often accompanied by the threat of attack and violence.

-

Connections Between Climate and Stability: Lessons From Asia and Africa

›“We, alongside this growing consensus of research institutes, analysts, and security agencies on both sides of the Atlantic, think of climate change as a risk multiplier; as something that will amplify existing social, political, and resource stressors,” said Janani Vivekananda of International Alert, speaking at the Wilson Center on May 10. [Video Below]

Vivekananda, a senior climate policy officer with International Alert’s Peacebuilding Program, was joined by co-presenter Jeffrey Stark, the director of research and studies at the Foundation for Environmental Security and Sustainability (FESS), and discussant Cynthia Brady, senior conflict advisor with USAID’s Office of Conflict Management and Mitigation, to discuss the complex connections between climate change, conflict, stability, and governance.

A Multi-Layered Problem

Climate change and stability represent a “double-headed problem,” said Vivekananda. Climate change, while never the only cause of conflict, can increase its risk in certain contexts. At the same time, “states which are affected by conflict will already have weakened social, economic, and political resilience, which will mean that these states and their governments will find it difficult to address the impacts of climate change on the lives of these communities,” she said.

“In fragile states, the particular challenge is adapting the way we respond to climate change, bearing in mind the specific challenges of operating in a fragile context,” said Vivekananda. Ill-informed intervention programs run the risk of doing more harm than good, she said.

For example, Vivekananda said an agrarian village she visited in Nepal was suffering from an acute water shortage and tried adapting by switching from rice to corn, which is a less water-intensive crop. However, this initiative failed because the villagers lacked the necessary technical knowledge and coordination to make their efforts successful in the long term, and in the short term this effort actually further reduced water supplies and exacerbated deforestation.

“Local responses will only be able to go so far without national-level coordination,” Vivekananda said. What is needed is a “harmony” between so-called “top-down” and “bottom-up” initiatives. “Adapting to these challenges means adapting development assistance,” she said.

“What we’re finding is that the qualities that help a community, or a society, or in fact a government be resilient to climate change are in fact very similar qualities to that which makes a community able to deal with conflict issues without resorting to violence,” said Vivekananda.

No Simple, Surgical Solutions

“The impacts of environmental change and management of natural resources are always embedded in a powerful web of social, economic, political, cultural, and historical factors,” said Stark. “We shouldn’t expect simple, surgical solutions to climate change challenges,” he said.

Uganda and Ethiopia, for example, both have rich pastoralist traditions that are threatened by climate change. Increasing temperatures, drought, infrequent but intense rains, hail, and changes in seasonal patterns are threatening pasture lands and livelihoods.

At the same time, pastoralists are confronting the effects of a rapidly growing population, expanding cultivation, forced migration, shrinking traditional grazing lands, anti-pastoralist attitudes, and ethnic tensions. As a result, “any intervention in relation to climate adaptation – whether for water, or food, or alternative livelihoods – has to be fully understood and explicitly acknowledged as mutually beneficial by all sides,” Stark said. “If it is seen in any way to be favoring one group or another it will just cause conflict, so it is a very difficult and delicate situation.”

Yet, the challenges of climate change, said Stark, can be used “as a way to involve people who feel marginalized, empower their participation…and at the same time address some of the drivers of conflict that exist in the country.”

Case Studies: Addressing the “Missing Middle”

When doing climate change work in fragile states, “you have to think about your do-no-harm parameters,” said Brady. “Where are the opportunities to get additional sustainable development benefit and additional stabilization benefit out of reducing climate change vulnerability?”

More in-depth case studies, such as the work funded by USAID and conducted by FESS in Uganda and Ethiopia, are needed to help fill the “missing middle” between broad, international climate change efforts – like those at the United Nations – and the community level, Brady said.

The information generated from these case studies is being eagerly awaited by USAID’s partners in the Departments of State, Defense, and Treasury, said Brady. “We are all hopeful that there will be some really significant common lessons learned, and that at a minimum, we may draw some common understanding about what climate-sensitive parameters in fragile states might mean.”

Image Credit: “Ethio Somali 1,” courtesy of flickr user aheavens.